- Introduction

- BBC Radiophonic Music

- The Radiophonic Workshop

- BBC Radiophonic Workshop 21

- The Soundhouse

- Coda

- Sources

Contents

Introduction – Leader tape

If you hunt around the UK’s second-hand retailers looking for interesting old records, what do you hope will turn up? If you’ve been at it for a while you will probably have a long list of labels, artists, styles and buy-on-sight items. For some of us there is a particular word that quickens the pulse – Radiophonic. The BBC’s special department for making the sounds and music not available to producers by other means was the Radiophonic Workshop. The Workshop was well represented on the BBC’s record label – BBC Records and Tapes – and the importance to the Corporation of the Radiophonic Workshop can been seen in the extensive catalogue of releases on which they feature.

The story of the Radiophonic Workshop has been covered thoroughly before. So, instead of an historically structured narrative, these blog posts are a review of releases on the BBC Records (and Tapes) label which contain appearances by the Workshop. The review seeks not only to catalogue the numerous Radiophonic specific releases but to highlight the less obvious and obscure places in which the Workshop has made its contribution across the BBC’s vinyl releases. And, yes, on a few cassettes too, but I won’t be going into the CD releases. There were thousands of works created by the Workshop during its time and only a fraction is available publicly. One of the aims of this review is to catalogue what Radiophony was released by the BBC and illuminate some of the darker corners.

Whilst this is not intended as a story of the Workshop, I’ve explored further into the context surrounding certain releases and added interesting details about certain pieces and their creators. Inevitably these tales tell part of the bigger story, albeit in a fragmented form. It’s the records and their context, not the artists or some other organising principle, that is the subject of this review and indeed this website.

I had originally intended to compile a simple list of all the BBC Records releases with a Radiophonic element to them and add a few comments. However, the more I tried to get the details right, the more interesting the details became (well, they were to me anyway) and I seemed to be in the grip of compulsion to keep writing. Hence I have ended up with 6 posts which cover different types of releases:

Part 1 – Compilation albums of Radiophonic Music released as showcases for the Workshop.

Part 2 – Solo albums by members of the Workshop

Part 3 – Doctor Who

Part 4 – Contributions to ‘The Goon Show’ and sound effects LPs

Part 5 – Children’s and Themes works, including related compilation albums.

Part 6 – A miscellany of other appearances and releases where some of the more obscure and unexpected contributions can be found.

I make no apology for digressing into the technological side of the Workshops because the means of production defined what results were possible and the direction the Workshop took. I’ve tried to make what I’ve written comprehensible to anyone with a general interest in the subject.

I have no training in art or design. I’ve tried my best with the cover designs so I will apologise for any pseudo-intellectual waffle. I think I’ve proposed some original ideas – and there is some factual information, at least.

Generally, I’ve not written a track-by-track review or attempted to describe the music and sounds. I’ve used the pieces as examples of a style or technique or tried to find stories behind their creation. Music theory is also not in my repertoire. A lot is available for you to hear for yourself and others have written plenty enough flowery verse. I have a mix of the more obscure odds and ends in the works and plan to issue this on Mixcloud to accompany part 6 though.

I’ve added a list of sources at the bottom of the page. Rather than litter the text with links and references I’ve simply left these for you to explore yourself. Please contact me if you want to query anything.

Now, let’s begin with the compilation albums of the Radiophonic Workshop’s music.

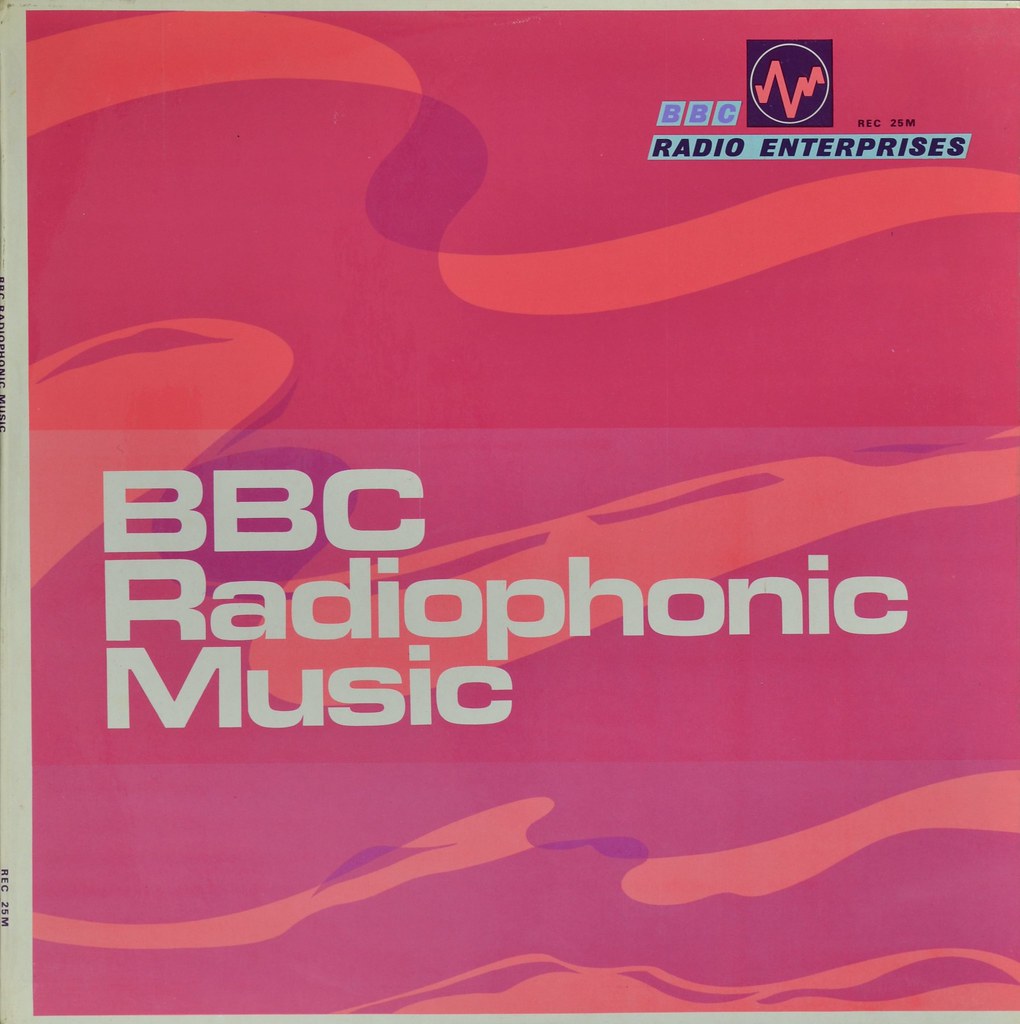

BBC Radiophonic Music

BBC Radiophonic Music was released by BBC Radio Enterprises in late 1968 to coincide with the 10th anniversary of the Workshop. The commercial wing of the BBC was in its third year and had got off to a slow start but there had been some success and things would be picking up over the next year. Many say that initially this first Radiophonic album was released only as a library record and therefore wasn’t made available to the general public until possibly the BBC Records label reissue in 1971. I can’t find a reliable or convincing source for that assertion and have reason to believe that this isn’t the correct story. Radiophonic compilations were made available to BBC producers before this release, presumably on tape. This was done at least two years before, although some pieces, like ‘Blue Veils and Golden Sands’, didn’t exist that far back, so this was a different selection.

Mark Ayres’ sleeve notes for the remastered 2002 CD state that the idea for a commercial release had been around since March of 1967. The first master tape of the compilation dates from this time (with two extra tracks, added to the re-mastered release). Also, this was a BBC Radio Enterprises release – in other words a commercial release. BBC Radio Enterprises had started out licensing recordings to other labels, but a library only release; a way for other broadcasters and film-makers to find and licence Radiophonic music, probably wouldn’t have interested them. The album was reviewed in Gramophone magazine in September 1969. This was quite late after the release but it must have been available to the public by then. Finally, I have a scan of a catalogue of BBC Records from late 1970. Listed under ‘For Enthusiasts,’ and costing 28/9, BBC Radiophonic Music is described as “A wide selection of electronic works from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop”. Decimalisation came in in February 1971, so it was available before that and the subsequent reissue in 1971.

Stop Press: Since writing this I’ve been able to ask Mark Ayres about this idea of a library only release. He has seen no evidence of it either. It may have just been pressed in small numbers to begin with.

Inside the BBC, tracks from this compilation were being used (or rather reused) for productions ahead of the ’68 release as they were available as “stock music”. During 1969 and 1970 tracks were used in Doctor Who, including the aforementioned ‘Blue Veils and Golden Sands’. Parts of the album (and other Radiophonic tracks) were also turning up on children’s LPs later in 1969 – more on those later.

Whatever the exact release dates, internal copies and other possibilities, the 1971 release on the BBC Records label was obviously intended to meet the continuing demand after the original run had been sold out.

The early releases from BBC Radio Enterprises got into a fair old muddle with their catalogue and matrix numbers. The Gold Label Edition releases seem to account for most of the confusion but there are others which seem to be simply missing. BBC Radiophonic Music was catalogue REC 25, but the matrix numbers are 25/5 and 25/6. This indicates that there were 25/1, 25/2 and 25/3, 25/4 before it. Indeed those records do exist. REGL 3 has matrix numbers 25/1, 25/2 and is Song of Myself, the poem by Walt Whitman read by Orson Welles. REGL 4 has matrix numbers 25/3, 25/4 and is Dohnanyi: His Last Recital by Erna Dohnanyi.

Sleeve Design

The sleeve design, variously described as ‘lurid’ and ‘psychedelic’, is by John J Gillbe and has led to the LP also being called ‘the pink album’. Whilst the overall effect is more restful than distressing or trippy, it is of the psychedelic moment. It may seem abstract at first glance but thinking about the imagery whilst writing this blog something else occurred to me. My interpretation* of the design is that the orange bands represent the medium of the music – magnetic tape. The topmost band is well defined and can be clearly discerned as a twisting ribbon, with the orange on one side and purple on the other. If this had been continued across the sleeve it would be fairly obvious that this was a straightforward representation of the Workshop’s stock-in-trade, but it’s more interesting than that. The subsequent bands are echoes or distorted copies of the original tape, becoming more indistinct and melting away towards the bottom. Perhaps reflections on water. This is a perfect visual metaphor for the Radiophonic Workshop: Recorded sounds are copied, cut, pitched, filtered, reversed, mixed, and so on, to create new sounds. This abstract new soundscape is represented on the sleeve as a landscape of sorts.

* I can only say that I came to this theory on my own and if it’s been advanced before, or even confirmed by those who would know, I wasn’t aware of it.

Track Selection

BBC Radiophonic Music is a confident and impressive demonstration of the first Golden Age of the Workshop. It contains musical pieces by composers John Baker, David Cain and Delia Derbyshire. This choice of tonal music is in contrast to the ‘special sound’ and contributions to serious drama which the Workshop was originally set up to provide. It also stands out from atonal and experimental music which was more common territory for electronic music at the time. Whilst often seen as experimental, the Workshop was set up to service BBC programming not to make artistic or exploratory statements of their own. Experimentation, in its truest sense, was being practised elsewhere and the techniques were being used by the Workshop, not created there. This is a moot point as the whole field was relatively new but the contribution being made at the Workshop was a refinement and perfection of certain ideas. It was partly this narrower focus that led to co-founder Daphne Oram leaving the Workshop soon after its creation.

For perhaps obvious commercial reasons, this selection was compiled with an eye to a wider audience and whilst it can still be a challenging listen for the more conservative listener – David Cain’s ‘War of the Worlds’ is downright frightening in places – its’ generally melodic approach illustrates how the output of the Workshop had headed away from its roots as an aid to radio drama. The sleeve notes by Desmond Briscoe reassuringly state that the intention is to entertain, not educate. That is an important distinction from some of the uneasy listening available elsewhere and the worthiness of the drama works. In other words, they may have started off doing high concept radio dramas and making audio tapestries depicting troubled mental states, but here’s ‘O come all ye faithful’ played on a cash register and ‘Boys and girls come out to play’ made out of who knows what.

This album is a showcase for John Baker’s swinging, jazzy, rhythmically entertaining pieces made by splicing tape together into loops, Delia Derbyshire’s romantic via analytical approach using concrete and electronic techniques in harmony and David Cain’s melding of early music, jazz and radiophony.

John Baker – Measure twice cut once and loop forever – c/o http://whitefiles.org

On show across the album are commissions from: local radio – Sheffield, Nottingham and Leeds Radio’s ‘Women’s Programme’ (presented here as Door-to-Door); BBC Schools – ‘Boys and Girls’, ‘Time and Tune’, ‘Autumn and Winter’, ‘The Frog’s Wooing’; and a variety of Radio and TV themes and incidental music. The range of styles, moods and techniques reflects that diversity of purpose.

The fact that the theme to Doctor Who is not included is noteworthy. Only ‘Ziwzih Ziwzih OO-OO-OO’ by Delia Derbyshire is from a science fiction production. A TV version of Isaac Asimov’s ‘Reason’ called for a robots’ hymn to their leader. The ‘ziwih’ chants are the singing voices of the cast reversed, whilst the ‘OO’ parts came not from a voice but from a piece of test equipment called the wobbulator. Derbyshire has hinted that the ‘OO’s were partially influenced by the Beatles’ ‘Please Please Me’ (‘like I please yoooooooooou’).

There was a real danger of the Workshop becoming pigeon-holed as being for sci-fi and strange sound only. This album deliberately sets out to show how wrong that view could be and that they were capable of fulfilling a diverse range of briefs.

Track Trivia

- ‘Radio Sheffield’ was made using a set of Sheffield Stainless Steel cutlery donated for that purpose.

- ‘Pot au Feu’ is mix of other tracks seamlessly spliced together. Hence it’s longer running time compared most other tracks on the album.

- ‘Reading Your Letters’ was built up from the glugging of a bottle of cider being poured and John Baker created a short explanation of how he did it, for Woman’s Hour (see The John Baker Tapes on Trunk Records).

- ‘The Chase’ is from John Baker’s score for series one of the BBC TV drama Vendetta.

- ‘Milk Way’ was constructed from the various sounds of a milk bottle and used for a programme about dairy farming. Missing the pun somewhat, a BBC Schools producer thought it perfect for a programme about space.

- The closing flourish to ‘New Worlds’ was for many years used as the closing sting to John Craven’s Newsround.

- ‘War of the Worlds’ is taken from the first programme for which David Cain created music and sound at the Workshop.

The Radiophonic Workshop

Four years after the 1971 reissue of the first such compilation, and setting a quadrennial pattern for subsequent collections, The Radiophonic Workshop was released in 1975. The Workshop’s tape catalogue shows that the selection was made and in the can by May of 1974, though.

Unlike its predecessor, this album wasn’t compiled from existing themes and idents. According to Dick Mills:

“This record, I don’t think contains anything [produced by commission]. [They] said ‘Oh, have a dabble and if we get enough we’ll put it together and put it out on a disc”.

[Robin the Fog interview]

Presumably ‘they’ were BBC Records and this request for ‘dabbling’ follows on from a similar one made two years earlier which led to a solo LP from Paddy Kingsland, Fourth Dimension. Was the success of BBC Radiophonic Music for the BBC’s commercial arm now driving the work of the inhabitants of Maida Vale, as well as the TV and radio producers? In fact some tracks were previous commissions, like Dick Mill’s ‘Major Bloodnok’s Stomach’, but it became Workshop policy to occasionally give composers the time to experiment and work on their own ideas and productions. The work environment was increasingly demanding and Desmond Briscoe recognised the need to give his staff some room to express themselves and to step off the treadmill now and then. The loss of Delia Derbyshire may have contributed towards the making of this policy

Also, as we shall see, some work was being produced to meet a demand for Radiophonic Music in its own right. This is a progression from the thinking behind the BBC Radiophonic Music album, where the feeling at that time was that electronic music in general was difficult and needed to become melodic to be palatable to the general audience. The previous album had been a development in this direction, running parallel to the Moog-based group of artists growing on the east coast of the United States. The consensus view on electronic music had now shifted from high-brow and serious to popular and increasingly accessible. Kraftwerk had very recently broken through in America with ‘Autobahn’ and synthesizers were appearing in the hit parade – for example ‘Popcorn’ and Wendy Carlos’ score to ‘A Clockwork Orange’, with its various ‘Moog plays the classics’ progeny. Meanwhile Giorgio Moroder and Chicory Tip were getting things started in the UK. There was a thirst for more.

Without doubt BBC Radiophonic Music, Paddy Kingsland’s Fourth Dimension LP in 1973 and a variety of other related releases since the last Workshop album had been a success for BBC Records and there was strong interest to be exploited commercially. The Workshop was uniquely well placed to capitalise on this opportunity, so little wonder it was something BBC Records were asking for.

Cover Design

The cover design, by BBC Records regular Andrew Prewitt, is another bit of visual metaphor, although not quite as elegant as its predecessor. With a synthesizer representing the ‘Radiophonic’ and a, err, workshop (well, it’s actually a shed) as the Workshop. The literal meaning is hard to miss, but no less fun or interesting for that. And yes, it’s a real shed. Desmond Briscoe the Workshop’s Head’s shed to be exact. As Dick Mills explained:

“that’s our boss’s shed, because he’s got an outboard motor there from his boat, [and] there’s a model yacht up there and an anchor there”. [Robin the Fog interview]

More on Desmond’s boats later! It’s a departure from the tape in a lava-lamp of the cover for BBC Radiophonic Music, instead playing up the Workshop (not studio, of course) angle and the often rough and ready approach taken to achieve cutting edge and state of the art results. There is a trait in the British that loves the romantic notion of anonymous back-room staff toiling away with basic tools to create world beating results. In this case there is more than some truth to that legend, and a sort of pride in it too. There’s also a tendency for self-deprecation and a jokey, get-in-with-the-put-down-first approach we British exhibit and that this image embodies. They perhaps also wanted to show it was about just getting on with a job. ‘Hey, it’s a workshop and the sounds may be far out but the budget isn’t, and we’re not progressive rock stars you know’! Another layer of meaning was there for the budget holders at the BBC to decode – the Workshop were definitely not showing off!

The image presented on the sleeve is also a break from the euro-mod-gone-psychedelic of the 60’s era. The cultural and political mood in 1975 had moved on from the previous decades’ Modernism and whilst there were still a lot of clean lines, bright colours and futurism around, culturally it wasn’t as well suited to the needs of this album to flaunt it. It would return later in the 80s though.

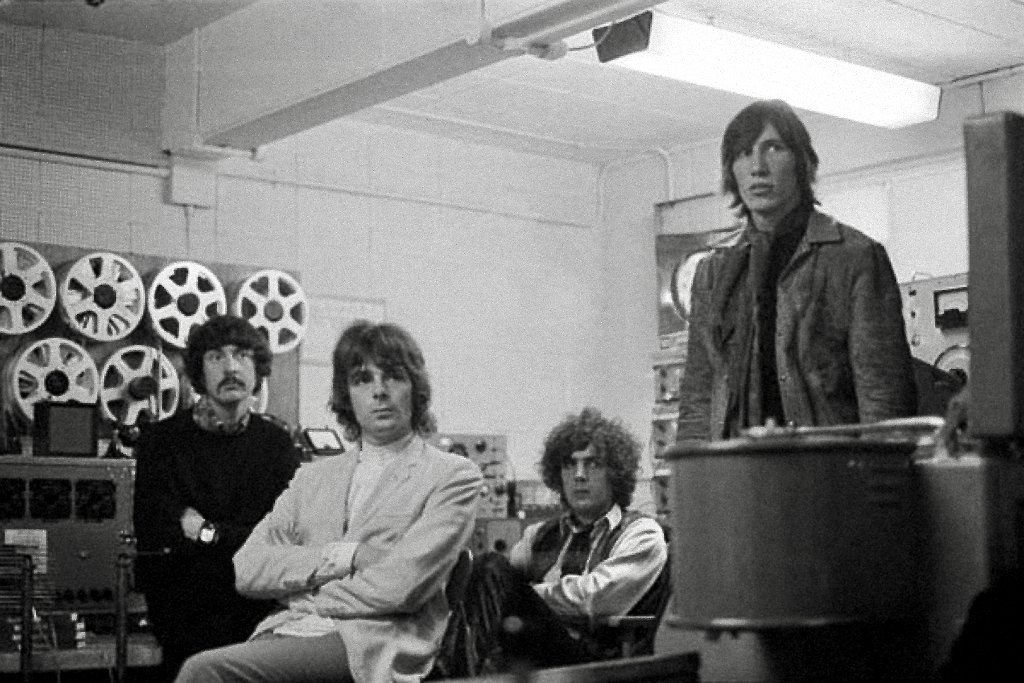

The cover-star synth is an EMS Synthi A. Annoyingly, for synth aficionados, the sleeve notes ruin the effect by stating that they actually used an EMS VCS3 on the album. Synthi A’s – a cheaper, more portable relation of the VCS3 – were around at the Workshop, though. They were still onto something, though, because the cool credentials of the smaller EMS synths were by now firmly established by the likes of Pink Floyd and Tangerine Dream. It’s probable that the Workshop had guided the Floyd towards choosing an EMS synth. In 1967, Delia Derbyshire had given them a tour of the Workshop and then, realising they were a little bemused by the junk equipment in use at Maida Vale, took them off to see Peter Zinovieff at EMS in Putney.

‘We’re up with the times’ was the other important message to get across, and ‘hey, heads, check out this far-out music made by mad scientists!’ was the equally commercially-savvy image.

Just to confuse matters, there was a workshop at the Workshop, inhabited down the years by a succession of engineers making, modifying, installing and repairing equipment for the studios.

Track Selection

Giving the composers freer expression and fewer constraints means the tracks are longer and less pithy than the selection of themes and indents on BBC Radiophonic Music. It’s just 12 pieces to enjoy with more of a conventional album structure.

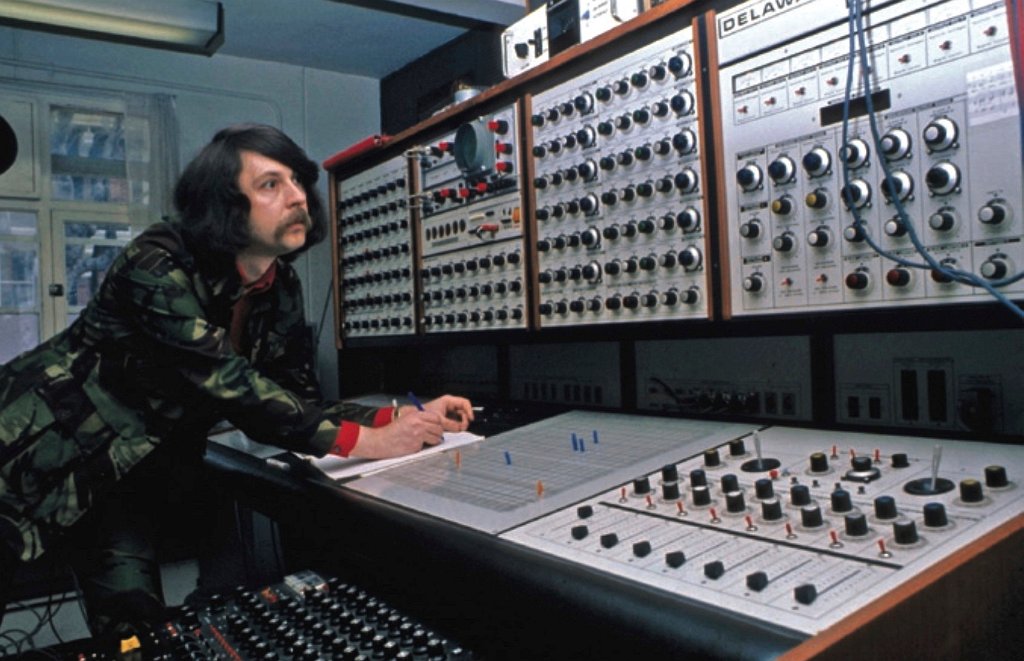

That ‘make do’ impression set by the sleeve is rather undermined by the opening track, ‘La Grande Piece de la Foire de la Rue Delaware’ by Malcolm Clarke, which was created on the not exactly low-budget Delaware synthesizer. The Delaware was a specially modified and expanded EMS Synthi 100 and was in its day the “largest voltage control synthesiser in the world”. Although the truly modular Moog systems were in principle infinitely scalable, this British monster came pre-loaded with 12 oscillators, which was not (and is not) at all usual. The 12 oscillators also effectively upgraded (and then some) the bank of 12 vacuum tube driven ‘Jason’ oscillators with jury-rigged keying unit used to great effect by Delia Derbyshire.

The Synthi 100 was actually more physically compact than its rival option from Moog. Desmond Briscoe had visited the Moog headquarters in the states and had been impressed by what he saw there. On his return though, EMS announced the Synthi 100 and the decision to order the more capable, and more British, instrument was made. In fact the Workshop was not awash with money in the early seventies and they were in a constant battle to get the latest equipment, particularly multitrack tape machines which cut the time to create work significantly and made more complex pieces possible. Having an 8-track machine to go with the Delaware was seen as a must, but became a battle of the budgets. Eventually, the Workshop prevailed and a Studer 8-track was placed alongside the Delaware.

‘La Grande Piece…’ is a tongue-in-cheek affair that could be best described as sounding like an electronic barrel organ. The foire/fair reference makes this link more explicit. Barrel organs can play various instruments, including percussion, from a barrel roll of pre-programmed music driven by mechanical means. The computer sequencer on the Delaware performs much the same function, so what you hear in La Grande Piece is the modern equivalent of a barrel organ and the music self-mockingly reflects that. It was a work commissioned by Radio 3 in 1973 specifically to show-off the Workshop in a programme called ‘The Space Between’. The hour and five minutes programme was described as “A stereo miscellany of music, sound and words from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop” and was part of Radio 3’s Stereo Week, where they were exhibiting the latest in audio technology to promote the addition of stereo to Radios 2 and 4.

The gradual move away from musique concrete tape techniques and on to commercially available synthesizers was not complete yet. The prominence given to the synthesizer on the cover – albeit one without a keyboard and thus, in terms of approaches to using synthesizers, having it both ways – underlined the shift that had begun over ten years before, towards the Workshop as a music production facility. The busy jazz rhythms of Baker’s tape loops on ‘Brio’ were giving way to the rock beat of Kingsland on ‘The Panel Beaters’, but they were both meeting the same demand for catchy melodies in a contemporary style. Far off, trouble was looming for the Workshop though. The programmable sequencer on the Delaware was still cutting edge stuff in 1975, and the synthesiser it drove is still impressive now, but, with the way that computers advance, it was inevitable that soon enough the pop mainstream would catch up. The unique advantage of musique concrete was that only a few brave and driven souls like Delia and John, in the rarefied conditions of a BBC department, could make it work to such exquisite peaks of musicality. Once computing power advanced anyone would be able to program a sequencer for their Mini Moog or Arp Odyssey. For now though it was the stuff of dreams for most musicians interested in electronics to be able to program anything into a computer and the Workshop was still out there at the front. Kraftwerk were touring with sequencers in 1975, but these guys were already in their own league. Years later The Human League would still be imitating sequencers playing by hand, or with rudimentary pulse generators, because it was still out of their reach.

Something else was being lost too though. The analysis and precision possible with test equipment were not what electronic instrument makers were providing better solutions for. This new direction frustrated Delia and led to her leaving the Workshop and losing interest in music making altogether. Yes, the Delaware may be indistinguishable from a nuclear power plant control panel to you, but to Delia it was like replacing her slide-rule with an abacus.

The album has fewer tracks than its predecessor, yet is just as eclectic as the first. Perhaps more so, as we have the benefit of the radiophonic techniques, the synthesizer and conventional instruments working alongside each other – all in stereo. On side 1 each track gives a different take on how to produce radiophonic music.

- ‘La Grande Piece de la Foire de la Rue Delaware’ – All made on the Delaware and multitrack tape.

- ‘Brio’ – A stereo rendering of the incredible Baker tape-loop work from ‘Vendetta’ (created in 1966) with swirling organ. This was also part of the commission for ‘The Space Between.

- ‘Adagio’ – Dick Mills’ atmospheric tour de force of ambient tones and twinkles. I have no idea how he made this but it terrified his wife, who refused to listen through to the end! It won’t be the first time we encounter it in this review either.

- ‘Geraldine’ – Roger Limb taking things Easy with a drum kit and synths.

- ‘Bath-time’ – Tape loop of sploshing and synths by Malcolm Clarke.

- ‘Nénuphar’ – More ambient moods, but again it’s hard to pin down what was used. I guess tape loops of synthesizers rather than concrete sounds.

If you want to hear how Paddy Kingsland put ‘The Panel Beaters’ together head over here to hear a short explanation of multitrack recording, look for the ‘Sound by Design’ clip: http://andywalmsley.blogspot.com/2017/09/time-to-go-home.html

BBC Radiophonic Workshop – 21

Another four years had passed since The Radiophonic Workshop album. It was now 1979 and 21 years since Daphne Oram, Desmond Briscoe and others were given space at Maida Vale studios, two grand in cash and their pick of the junk equipment no-one else had use for at the BBC, in order to create the sonic equivalent of a mental breakdown. What better way to celebrate the coming of age of the Workshop than another album. By this time the last of the original golden era ‘concrete mixers’ had long gone and the tiny pieces of tape with them. Desmond Briscoe was still in overall charge, though, and Brian Hodgson had returned and was now running things day-to-day. The dazzling new world of digital sampling hadn’t quite started yet though and the leap forward this time was better versions of what they already had. Expanded multitrack tape, mixing and effects facilities and polyphonic synthesisers, that could play more than one note at a time, had started to appear.

And, why not provide a more balanced record of the early days? BBC Radiophonic Music had only covered three composers after all, and there was plenty in the tape library to draw upon. It’s worth noting here that thankfully the Workshop kept its own archive and in general did not suffer from the brutal wiping and disposal of tapes commonplace at the BBC in the sixties and seventies. There was a close shave at the end, though. Thankfully a combination of simple bureaucratic indifference and Mark Ayres’ frantic scouring of Maida Vale was able to avert the destruction of years of tapes.

Cover design

It’s their birthday, so… candles? There is no cake though, just candles. The candle-light is diffracted somehow, so the dominant impression is of red, green and blue splodges. Despite its having nothing discernible to say about Radiophonic music, I rather like this design – because of the typeface and the simple lighting effects, but also because it looks like little else and has few other associations. Little else, except perhaps for one particular association – the new opening titles to Doctor Who which came to our screens a year later, in 1980. The prismatic effects are applied to a starfield in that case.

Track Selection

A generous 45 tracks and probably the best introduction to the Radiophonic Workshop. If you only get one Radiophonic album it should be this one. Side one is the early tapes and test equipment years up-to 1971. Side two covers the synths and multitrack era up-to ‘79. If you wanted to get a better idea of the chronology of things you could play side one after BBC Radiophonic Music then side two after The Radiophonic Workshop.

The Workshop wasn’t just inhabited by a select bunch of permanent composers and engineers. There was a policy of 3-month secondments for BBC producers, studio managers and other lucky staff to the Radiophonic Workshop. This was how everyone got started at the Workshop for most of its history. Many less celebrated names turned out some special sounds before returning to programme making. This review of the first 21 years includes a few such names alongside the more familiar stars.

Tony Askew seems to have been at the Workshop for a short time in the mid-sixties and left only a couple of recordings in the archive. ‘Secrets of the Chasm’ is the only release from his time at the Workshop but richly deserves its place here. It was presumably written to accompany the 1966 ‘Adventure’ programme of the same name, an exploration of what was once thought the deepest cave in the world, Gouffre Berger. It’s a deeply moody and atmospheric piece.

Keith Salmon was at it with the tapes and oscillators from 1965 to 1966 and would later commission works from the Workshop as a radio producer. His contribution here is ‘Westminster at Work’, evidently created from the inner workings of Westminster’s clock and Big Ben. Keith was around long enough to be in a photo of the staff – between Delia and Brian – but not long enough to make any kind of mark on the discography.

‘Know Your Car’ was Delia’s signature tune to ‘Family Car’ and therefore does not appear on the single from the similarly named series ‘Know your car and get the best out of it’, which has its own release from BBC Publications – OP 7. In any case, it’s very welcome here. Apparently the stop-start, cough and parp of the automobile sounds in this theme were considered likely to offend a certain manufacturer who was providing cars for the show and so the producers got cold feet and turned it down. It did get some use, though, under the title of the song it is based on (from 1913), called He’d Have to Get Under – Get Out and Get Under (to Fix Up His Automobile). Radio Stoke-on-Trent used it and it was one of the tracks selected to be played as part of Radiophonic concert at The Royal Festival Hall before the Queen in May 1971.

Album Highlights

- Workshop Organiser Desmond Briscoe’s Special Sound for BBC television’s Quatermass and the Pit from the very early days in 1958. It was the first time electronic sound had been used in a British science fiction production.

- Dick Mill’s dicky tummy recorded for the Goons’ Major Bloodnok (“no more curried eggs for me!”) is back again and will be repeating on us a few more times.

- ‘Science and Industry’, by engineer Phil Young, was the first ever electronic signature tune at the BBC and was used by the World Service for many years,

- Maddalena Fagandini’s ‘Timebeat’, written to fill in the gaps between TV programmes from the days when they did not all run to the schedule. This deceptively simple rhythm track would later get the mash-up treatment by none other than fifth Beatle, Biggles himself, and released on a Parlophone single under their Ray Cathode pseudonym way back in 1962. The b-side – ‘Waltz in Orbit’ – where Maddalena works on top of George Martin’s rhythm track, is better though.

- Maddalena Fagandini’s ‘Ideal Home Exhibition’ – an example of music for the BBCs’ promotional and other activities beyond programming.

- Delia’s ‘Science and Health’, which was rejected for being too lascivious for the sex education programme it was written for and so sarcastically subtitled ‘Mike’s Choice’ after the priggish producer. Tantalisingly, it had lyrics written for it which were never recorded. The backing track was reused for ‘Ziwzih Ziwzih OO-OO-OO’ though.

- Delia’s ‘Doctor Who’ and Brian’s ‘TARDIS’ – of which much (much) more later on.

- Dudley Simpson gets an honorary Workshop credit for ‘Minds of Evil’ from the Dr Who story, err, ‘The Mind of Evil’. The track is more properly called ‘Keller Machine Theme’ (sorry about all this) and was realised from Simpson’s score by Brian Hodgson. The entire eighth season was scored by Simpson and then produced electronically by the Workshop, on their EMS VCS3s .

- Peter Howell’s smash hit ‘Greenwich Chorus’ – which we will return to later.

- Roger Limb’s theme tune to transmitter engineering bulletins, ‘Swirley’. According to the Workshop tape archive this was created for BBC2 and the producer was called Shirley Edwards. Swirley Shirley I suppose.

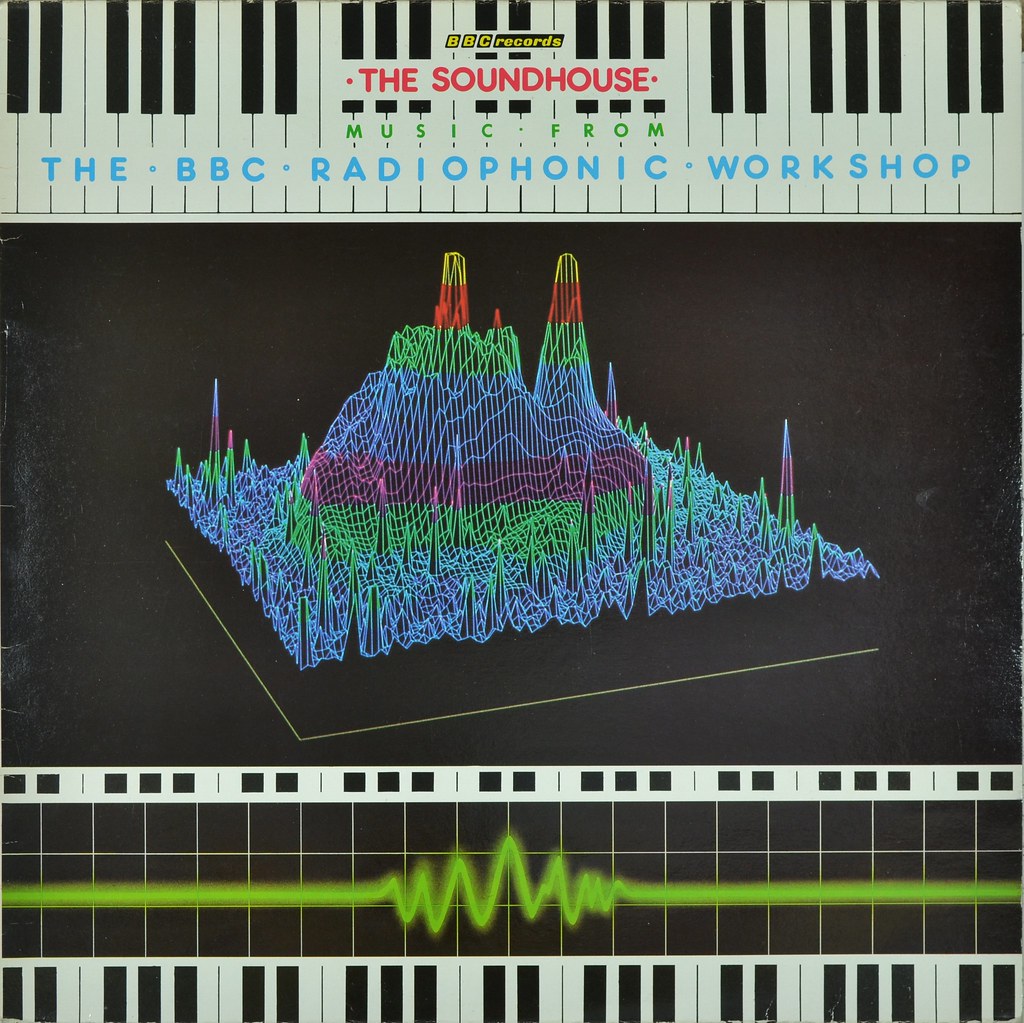

The Soundhouse

The Soundhouse was the final compilation album of Radiophonic Workshop music to be released on vinyl and while it was still a going concern. Following the four-yearly interval rule this LP was released in 1983 which coincided with the 25th anniversary. Desmond Briscoe retired that year and co-wrote a book The BBC Radiophonic Workshop: The First 25 Years with Roy Curtis-Bramwell. Arguably this was the end of an era, although the Workshop would continue for another 14 years before finally being closed in 1997. In any case, four years after this album no showcase for the Workshop was released. There were plenty of Radiophonic works released on BBC Records in the years afterwards, as we will see later.

The title is a reference to an extract from Francis Bacon’s techno utopian vision from 1627:

We have also sound-houses, where we practice and demonstrate all sounds and their generation. We have harmonies, which you have not, of quarter-sounds and lesser slides of sounds. Divers instruments of music likewise to you unknown, some sweeter than any you have, together with bells and rings that are dainty and sweet. We represent small sounds as great and deep, likewise great sounds extenuate and sharp; we make divers tremblings and warblings of sounds, which in their original are entire. We represent and imitate all articulate sounds and letters, and the voices and notes of beasts and birds. We have certain helps which set to the ear do further the hearing greatly. We also have divers strange and artificial echoes, reflecting the voice many times, and as it were tossing it, and some that give back the voice louder than it came, some shriller and some deeper; yea, some rendering the voice differing in the letters or articulate sound from that they receive. We have also means to convey sounds in trunks and pipes, in strange lines and distances.

It was Daphne Oram who had posted this passage from The New Atlantis up in the Workshop in the early days and it was probably only now that all of those predictions had come fully into reality.

Sleeve Design

The year was 1983, the brown on brown, analogue 70s was firmly behind us; new pop dominated the charts, synths were ‘Compuphonic’ and everywhere, and the BBC Micro was beaming classrooms into the future. In design terms we have a kind of Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures realised by Italy’s Memphis Group. The rounded sans serif font in primary colours, 3D rainbow spectrogram and neon oscilloscope pulse, all with a piano tie border, ticks so many ‘the modern 80s’ boxes it could almost be a parody. Fortunately BBC Records’ designer Mario Moscadini balances the elements carefully and the overall confection is quite fresh and pleasant whilst still being suitably excited about technology. This is graphic design and no mistake. The job of Graphic Designer in the 80s was a pinnacle of a certain kind of yuppie aspiration, with its promise of Apple Macintosh computers, open-plan warehouse-conversion offices and Filofaxes. This design is just the kind of thing that you would be knocking out before checking your Filofax and driving off in your Porsche 911 turbo, we supposed. I’m trying to say it was very much of the moment.

The spectrograph is there to represent the exciting and expensive new world of digital sampling and computer based editing and sequencing. The Australian made Fairlight CMI was the must-have music technology of the early eighties and the Moog modular (or if you were an institution, EMS Synthi 100) of its day. Essentially it was a computer for recording, manipulating and playing back sound. Now it looks like a boring green-screen dinosaur of a computer, with a nondescript keyboard attached for doing something musical. Then, Trevor Horn bossed the charts with his Fairlight and formed The Art of Noise to fully explore the possibilities of it. He even had a full-time technician to wrangle it, J.J. Jeczalik. The only other people with one in the UK initially were Peter Gabriel, Kate Bush – and the Radiophonic Workshop. They took delivery in 1981, so it had been thoroughly explored by the time this LP came out. By April of ’83 Heaven 17 had theirs on stage on Top of the Pops, starting an era of £40K-gear-boasting unseen since ELP were in their heyday. Duran Duran and Jan Hammer were also swanking around with rolled-up jacket sleeves bathed in the glow of a Fairlight soon after.

The screen (or VDU, as we were all told these things were called, and then never ever did) was monochrome only. If this plot was rendered from a Fairlight (via the Voice Waveform Display) it was coloured in afterwards. I suspect it wasn’t though. It seems to have been coloured as it was drawn and not simply filtered afterwards, so I reckon it’s from a stock photo from something else entirely.

The Fairlight and its similarly pricey rival the Synclavier were a relatively short-lived phenomenon. Ever increasing computing capacity washed them away and soon the cheaper EMU Emulator was in every teenager’s bedroom being used to simulate norovirus so they could take a Day Off school. Meanwhile, Akai were plotting a course to sampler domination. However, the idea of a computer, with screen and keyboard, as a music making device would be back and that would largely kill off the standalone samplers which had done for the Fairlight.

Track Selection

Roger Limb’s sleeve notes explain that the two innovations on this album are the “Fairlight Computer Synthesizer” (see above) and the fact that they are including tracks which blend electronics with traditional instruments. As he makes clear, this meeting of worlds is nothing new in itself. The Workshop had been doing this from the earliest days. From Ray Cathode to John Baker’s jazz flutes and loops to Dick Mills’ realisation of the Moonbase theme and Paddy Kingsland’s music for The Changes, right through to Roger Limb’s own work on The Box Of Delights the following year, the Workshop has never been a purely electronic music studio. What Roger is saying is that this is the first time we’ve heard a lot of this on the Radiophonic compilations. I would also argue that the difference now is that we have to listen a bit harder to discern what is real and what is artificial. The technology is now at a point where it needn’t sound like it.

Flute on cave exploring atmosphere ‘Lascaux’, drums on the propulsive ‘Rallyman’ and ‘Cello’ on the chilly ‘Ghost in the Water’, all by Peter Howell, and Trombone on Malcolm Clarke’s theme to ‘Believe it or not!’ showcase a variety of approaches to the acoustic and the electronic working together.

Also noteworthy are the three classical pieces. In the early days of the Workshop there were a lot of nursery rhymes and folk songs getting the musique concrète treatment, owing to the BBC Schools department’s commissions. Delia Derbyshire turned in ‘Air on a G string’ on BBC Radiophonic Music, as ‘Air’, but they generally steered clear of Wendy Carlos style ‘switched on’ classics. Peter Howell’s ‘Land and People’ revisits his stately and elegant work for The Body In Question here and this is typical of an embracing of classical tropes. By now technology had made electronic music less laborious and, with a production-line of scores to churn out, the Workshop composers were probably very happy to bypass the composition stage now and then. So we have: ‘Mainstream’ written, sorry, attributed to Henry VIII; ‘Fancy Fish’, a Fairlight rendering of ‘Aquarium’ from The Carnival of the Animals by Camille Saint-Saëns (with the help of the sound of an aspirin tablet dropped in a glass of water); and another Fairlight effort called ‘Houdin’s Musical Box’ by the altogether more obscure A. Le Carpentier. Elsewhere there are classical flourishes aplenty as the ability to produce music of increasing sophistication was at their fingertips.

The third track is probably the closest auditory equivalent of the sleeve design. ‘Computers in the Real World’ is an upbeat, cheery theme with the sounds of a real computer’s disk drives forming part of the rhythm track. It’s essentially the same kind of ‘music made from the sound of the thing the programme is about’ approach pioneered in the earliest days of the Workshop. The difference was that whilst it used to take days, if not weeks, now Jonathan Gibbs could have been on to the next thing within hours. Another link with the past is Elizabeth Parker’s ident for Radio Blackburn from 1980.

The TV adaptation of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was screened at the start of 1981 and, continuing the work he had started for the radio series in 1978 (and then stopped and then started again), featured a score and effects by Paddy Kingsland. Two music tracks are included here: the clownish, balletic ‘The Whale’ and dreamscape ‘Brighton Pier’. The scene with the ill-fated and innocent sperm whale (a former a nuclear missile, you understand) is essentially a piece of darkly comic, large-scale slapstick which the music conveys perfectly. Unfortunately, it is a quite conventional piece and I regret its inclusion when other more interesting passages could have been chosen. I suppose it was one of a few fairly complete pieces, though, and mixed up the moods of the record nicely. These are the only excerpts from the score available anywhere so we’ll take what we can get. I’m much happier with the infinitely improbable appearance of ’Brighton Pier’ (which Arthur thinks might be Southend). I will be so bold as to say that this piece presages some of the atmospheres and delicate flourishes of Vangelis’s score to Bladerunner, released a year later. Oh, yes I will! Kingsland left the Workshop later that year so this was some of his last work as a BBC employee but not his last commission.

Coda

Soundhouse was the last compilation released on vinyl and on the old BBC Records label. However we can imagine what might have been on a 1987 or 1991 or 1995 album, because many tracks from after 1983 are included on a CD compilation: BBC Radiophonic Work – A Retrospective.

Sources

- Special Sound: The Creation and Legacy of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop (Oxford Music/Media Series) – Louis Niebur

- The First 25 Years: The BBC Radiophonic Workshop – Roy Curtis-Bramwell and Desmond Briscoe.

- The Story Of The BBC Radiophonic Workshop http://www.soundonsound.com/people/story-bbc-radiophonic-workshop

- http://www.mb21.co.uk/ether.net/radiophonics/intro.shtml

- http://whitefiles.org/rwi/index.htm

- http://wikidelia.net/wiki/BBC_Radiophonic_Music

- http://wikidelia.net/wiki/BBC_Radiophonic_Music_(review_in_Gramophone)

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/bbcradiophonicworkshop/

- The John Baker Tapes – BBC Radiophonics, Electro Ads, Soundtracks, and Rare Home Recordings – Volumes 1 & 2 – Trunk Records

- http://wikidelia.net/wiki/Ziwzih_Ziwzih_OO-OO-OO

- Delia Derbyshire talking about Ziwzih Ziwzih

- Alchemists of Sound – BBC (2003)

- https://robinthefog.com/2014/05/14/the-music-of-the-spheres-dick-mills/

- http://wikidelia.net/wiki/Pink_Floyd

- The Space Between – Genome

- The Space Between in Radio Time on mb21

- http://wikidelia.net/wiki/Know_Your_Car

- He’d Have to Get Under – Get Out and Get Under (to Fix Up His Automobile)

- http://wikidelia.net/wiki/Science_and_Health

Comments are closed.