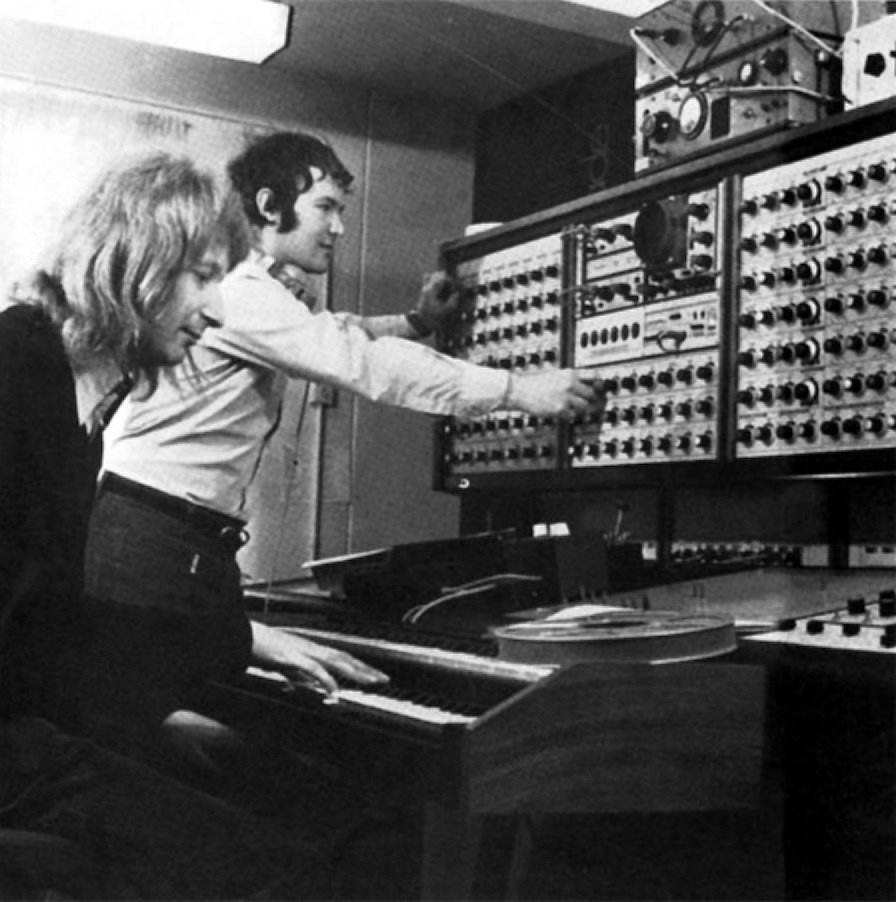

John Baker and Paddy Kingsland getting to grips with the Delaware

- The Space Between Blog Posts

- Take Another Listen

- Play Your Test Cards, Right?

- Into The Fourth Dimension

- Sources

Contents

The Space Between Blog Posts

Welcome to the second post of the second of six parts of Discographic Workshop, which is all about the Fourth Dimension album. If you’ve made it past that last sentence you can be assured, it gets easier from here on in. This addition to my ongoing review of all the Radiophonic Workshop’s appearances on the BBC’s record labels got so long, in particular, that I decided to split it out into its own post. Once that was decided, the brakes were off and the editing went for an extended tea break.

Take Another Look Listen

I had no idea I was going to write so much about this album, as it was one that I’d had difficulty getting on with, to begin with. The compilation albums (see Part 1) had been my introduction to the Workshop’s output. The more unconventional nature of much of that work, as well as the cherry picking of the best material, had left me eager to hear more but probably prone to disappointment. Consequently, when I eventually acquired this disc I was a little underwhelmed. It wasn’t bad, I thought, but it was all definitely from a certain period of pop music and not as uncompromisingly electronic as what I was familiar with. Writing this piece has given me a chance to reappraise the album as both music and as an artefact in the story of the Radiophonic Workshop, of BBC Records, and of the BBC more generally. It’s also a chance to have a closer look at Paddy Kingsland.

This 1973 album of “synthesizer music from the BBC Radiophonic Music” was originally conceived as an LP of test-card music. The first part of the review covers the story of those origins and includes some rather laboured playing card puns.

Play Your Test Cards, Right?

In 1971 Jack Aistrop of BBC Records had an idea which he brought to the Workshop head, Desmond Briscoe. Aistrop wanted to commission an album of Radiophonic pop music. The music would be music played with the test card and be released to the general public. If you are of too tender an age to remember the test-card, then head over here.

Ordinarily, these test transmissions were not something the viewing public were being directed to enjoy – they were intended for use by the ‘trade’, i.e. people selling and installing TVs. The music was entirely incidental and served only to avoid the alternatives. Silence would have made testing the audio element of the broadcast reception impossible and a test tone, whilst useful technically would still have been extremely tedious for the engineers and most annoying for viewers waiting for programmes to start. I can well remember staring into the testcard, with the short test-tone that was broadcast at the start of transmissions, waiting for the music to kick in so that then Playschool could “follows shortly”(sic) after. I think I can recall pestering my mom to turn the TV on, even though she told me it wasn’t time yet and was content to sit through the test card rather than do something else. Kids, eh? But this is a common experience for my generation.

Test Card Tricks

The reason Aistrop came to ask for a test-card album from the Workshop is rooted in the fact that normally the test-card music was not commercially available in Britain. First, commercially available music would have cost the BBC a pretty penny in royalties, so a cheaper alternative was needed. Normally that would mean library music, except in the UK that was also problematic. Because of Musician’s Union rules, none of their members could make library records. To understand why this was stipulated would take another article (also, I’m not entirely sure I understand it anyway), but the MU had a number of issues with recorded music in general. The MU’s preferred option would have been for the BBC to pay full rate for UK commercial recordings. But then they would have also had to fulfil a quota for live music to offset this recorded content too. ‘Keeping music live’ was the name of the MU campaign. It was a headache for broadcasters. So, to keep things cheap and simple the beeb used foreign library music, which they could licence at discounted rates and avoid all the issues with the MU. Phew!

This foreign library music came with its own terms and conditions, though. It may have been played by foreign musicians, who were not subject to the MU rules (or it might have just been played by UK musicians recording whilst ‘on holiday’!), but the licensing for library music was based on the fact it wasn’t dependent on the rights of the original artists. It was made by the yard and to commission, and the composer and players waived the normal rights to royalties for a flat fee and certain limitations on how the recordings could be used. Thus, the BBC would pay a smaller licence to the library labels, there being no artists to pay on top. Consequently, the music could not be released commercially in the UK either. The original artists didn’t mind their stuff being used on films and TV productions because no-one else was profiting directly, but a hit album would be a different matter if they didn’t see another cent! Clearly, this wasn’t always the case. Some library music was, and continues to be, sold to the public. Parts of the BBC Records catalogue depend on this. However, the terms for the test card music licensing were evidently quite strict and the cost of releasing it to the public not viable.

So what? Well, the fact that this test-card music was intended as aural wallpaper didn’t prevent demand building up for a commercial release. As well as hundreds of thousands of pre-schoolers staring at frequency gratings and plotting Bubbles the clown’s next noughts and crosses move (until they realised it wasn’t clear who was noughts and who was crosses), many adults were also quite enjoying the strains of the Cologne Radio Orchestra et al. This was muzak of a very high quality – they didn’t just throw any old rubbish on to the tapes. Hence the BBC and BBC Enterprises and their record label were receiving letters from people hoping to find out where the music could be bought. How frustrating to be presented with a demand that could not be met! Or could it? BBC Records decided to capitalise on the thirst for test card music in two ways.

Test Card Monte (or Find The Girl On The Test Card)

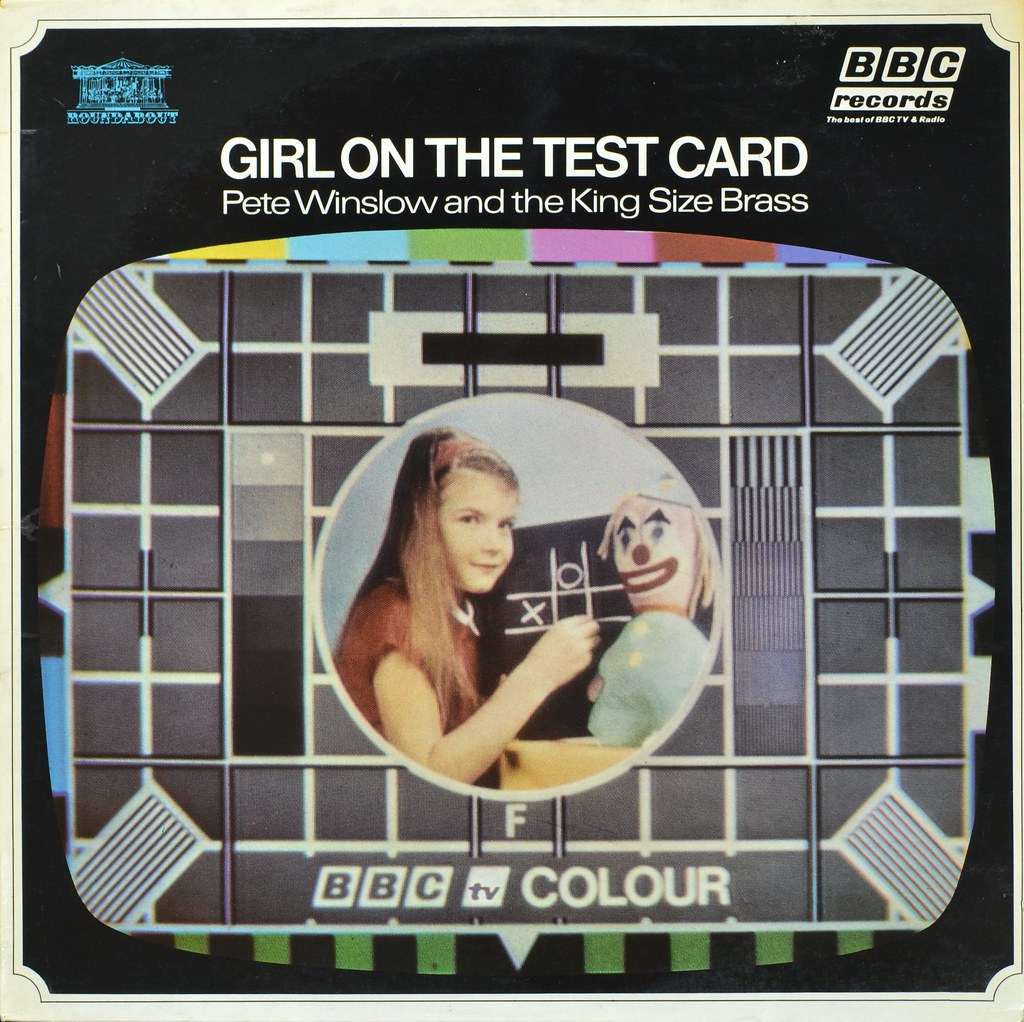

They may have been dealt a bad hand in terms of releasing genuine test-card music (I’m sticking with this card theme, sorry) but BBC Records fans will know that there was a tie-in record, also released in 1973: Girl on the Test Card (RBT 103). This was a load of Tijuana tinged jazz and ‘easy on the funk’ instrumentals by Pete Winslow and his King Size Brass. Somewhat like the three-card monte trick though, the public were being misled. None of the music on this LP was ever broadcast with the test card. It is ‘in the style of’ the library music being used on the trade tapes (as they are known), but not actually that music. The sleeve notes state in a circumlocutory fashion, that “this is the sound that could indeed easily be Test Card music”. So, the sleight of hand is not completely hidden.

As this was merely an imitation of test-card music the clamour for a release was supposedly being met, without giving people what they thought they wanted. In the event, the average punter had very little idea what the music was anyway, so an imitation would be just as good, right? But the chairman of The Test Card Circle, Stuart Montgomery, has told me that as a boy he passed on buying this album on its release because it wasn’t the actual music. So, you can’t fool all the people! It should be noted that the only person to be expelled from The Magic Circle had revealed the secret of the three-card Monte on TV, so these ‘circles’ are not to be trifled with!

Jack, Queen, King(sland)

Jack Aistrop had another test-card trick up his sleeve. His next wheeze is not totally clear to me, but he presumably reasoned that as well as releasing some imitation test-card music he could perhaps find some music that he could both get onto the test-card transmissions and still sell in the UK. In other words, create demand by having music broadcast for hours a day on both BBC TV channels and hopefully get many of the viewers clamouring for records he had made available in shops already. After all, no-one chose that music in order to sell it, so, what if there was something you wanted to sell being played for hours on TV? This is where the Radiophonic Workshop came in (finally!) – they were the joker in the pack (look, just go with it, I’m almost done, alright?).

The BBC hold the recording rights to an enormous amount of music, so the costs of broadcasting and releasing it are effectively free to the corporation – there’s no point paying themselves a license. But the Musicians’ Union rules on the one hand and the performers’ rights royalties on the other led to foreign library music being used for the test-card. However, the music produced by the Radiophonic Workshop fell outside those rules, somewhat.

Initially, there were no performing rights licensing issues at the Workshop at all. It seems to have been a condition of the Workshop’s existence that performing rights were not registered. Later, John Baker successfully challenged this and then it was up to the composers to register their own works. Mechanical recording rights stayed with the BBC, though. The situation with the MU is less clear. As the Workshop was producing ‘tape music’ the MU probably barred them from joining on principle.

In addition, perhaps thefact that a complete piece was created by a single person – almost unheard of at the time, as composers and musicians could have all taken a cut – made it a more commercially viable option. BBC Records could thus have their cake and eat it, thanks to the unique nature of the Workshop – getting free airplay and not paying through the nose for it later in royalties. With a successful LP of Radiophonic music still being pressed and re-pressed, BBC Records must have been getting quite excited about all the possibilities. And we haven’t even talked about synthesizers yet!

Obviously, this commission called for bright and breezy, tuneful toe-tappers not some of the more chilly and frightening atmospheres that Workshop was also known for.

Test card music had to be palatable to all-comers at all times of the day. In other words, this would be a pop album. Radiophonic pop was a new idea and one that Desmond Briscoe was rather interested in following up on.

Playing the Last Hand

Two tracks from the Fourth Dimension album – ‘Vespucci’ and ‘One-Eighty-One’ – were added to the end of a test-card tape which was broadcast from June to December of 1974. Being at the end of the reel, they were probably only heard very rarely, though. Also, the tape was already quite long, so the odds of hearing it were reduced even further. Why was it at the end? I did ask John Ross-Barnard, who is the patron of the TCC and was actually responsible for compiling this tape. Alas, it was all too long ago to recall such trivia. It isn’t all that surprising, though, when you consider that the Radiophonic grooves of Paddy Kingsland don’t sit that comfortably alongside The Edmund Vera Orchestra.

In the end then

The fact that this tape was from a year after the release of the LP suggests it was not exactly the co-ordinated media blitz that BBC Enterprises would have liked to promote their wares. Jack’s idea – if it was indeed his plan, and not just my misreading – was carried through, although it was a bit of a busted flush in the end.

Somewhere along the line the notion of a Radiophonic test-card album was dropped. Maybe they simply decided to do the album of ‘test card style’ music instead – Girl on the Test Card – or the test-card compilers at BBC presentation didn’t want the avant-garde on their reels. Or maybe they just tired of the whole idea. Perhaps there was enough electronic music seeping into the charts between 1971 and 1973 to make this electronic pop LP more viable as a stand-alone idea. Or, maybe, Paddy’s royalty cheques were still too high a price to pay despite the fact that they were still relatively cheap.

Into The Fourth Dimension

Hot Potato

The commission for an LP of Radiophonic pop music had remained alive and became ‘Fourth Dimension’. Apparently, Desmond Briscoe originally considered David Cain for this project, but apart from being too busy, Cain had established himself as both more high-brow and, err, medieval since he’d started at the Workshop. Instead, the assignment went to Briscoe’s “pop composers”: John Baker and new boy Paddy Kingsland.

Plans for John’s contributions were well advanced and a record sleeve design was produced with both a Baker and Kingsland side – something I would love to see one day. Unfortunately – most unfortunately indeed, as it transpired – John Baker was not up to the task and his pieces were never completed. He did make a start, but it soon became evident he wasn’t going to be ready in time. It’s not clear if this was simply because there wasn’t time amongst his other assignments, there wasn’t time for what he wanted to do or – more ominously – he wasn’t up to the task. Accounts vary, but Baker wasn’t well. This period was during the slide into depression and alcoholism which eventually led to his being let go in 1974. It’s doubly sad that this was the end of a brilliant career in both the BBC and electronic music and that we didn’t get a whole side of John’s music to enjoy in the dawn of the synthesiser era. Unfortunately for the old guard composers, expectations had been changed by multitrack recording and synthesizers. Composers were now expected to be able to work quickly and sadly it wasn’t a change that John was willing or able to make.

With John unable to meet the deadline, his apprentice Paddy Kingsland was given the “hot potato” of producing both sides of the album and the prize of a solo showcase. A hot potato was Brisco’s favourite metaphor for any difficult job that he had to throw to one of the composers. Of course, if handled properly, a hot potato is a prize worth having, so Paddy got busy.

The Baker’s Apprentice

Paddy had joined the Workshop in 1970 and was the first composer to take up residence who was steeped in rock and roll. Previous composers’ musical backgrounds had been jazz, or in the case of Delia Derbyshire more formally classical. Desmond Briscoe had the necessary vision to see that someone like that, with a rock and pop background, would serve the Workshop well when it came to commissions in that style, as well as being able simply to record music rather than to assemble it one note at a time. Accordingly, as we’ll see, ‘Fourth Dimension’ was far more conventional, musically. Kingsland’s approach was more traditional and as well as rocking it he could be folky too. In simple terms, he was writing songs. He has said that he didn’t feel he was really doing Radiophonic music, in the sense of using the full potential of the Workshop, till he worked on Hitchhiker’s Guide to Galaxy, a decade after he’d started there!

“Fourth Dimension” was intended to be one side of me and the other of John Baker. John was ill and so I did both sides, re-working theme tunes which started out as 30 second pieces, such as “Colour Radio”, “Fourth Dimension”, “Scene and Heard”, “Take another look”. I played guitar and a bass a lot, there was a drummer and bass player on some tracks. I used a mixture of 8 track and 1/4 inch overdubbing. I used VCS3, Synthi 100 and Arp Odyssey plus my old Telecaster.” [Astronauta Pinguim interview]

The Critical Perspective – Pop Art or Ersatz Pop?

I think it’s fair to say that this album remains a curiosity piece. Despite its popular framing, ‘Fourth Dimension’ certainly didn’t break through as a hit in the way that Aistrop and Briscoe might have dared to hope. Why? There is a lack of emotional weight to much of the music on this album, and there’s not quite enough style to make up for this lack of substance. This is no slight on its composer though. Popular music may have some guidelines, but there is no guarantee of success. Novelty can be an easier route to success if you get it right, and presumably, the label’s hopes were pinned on this aspect to do some of the heavy lifting. But in retrospect, the material isn’t weird or wonderful enough to make it as revered as the (almost uniquely awesome) musique concrete of the so-called first golden age of the workshop. And it is too orthodox in its aping of early seventies pop to break free completely and set electronic music on a new course. So, not novelty enough and Paddy was not a recording artist anyway. He was writing to order not pouring his heart out. That, at least, explains why it wasn’t then and (I would argue) isn’t now held as a landmark in the genre.

We now come to a conundrum: was this even a pop album in the first place, or was it something else? Is it even fair to try and compare it to artist-led releases? Whilst themes and music for picture are essentially applied art, they can, of course, transcend that functional origin. The whole point of Pop Art was to contextualise applied arts and thus create a form of pure art. Music for picture more easily blurs the applied/pure distinction, which is more readily apprehended in the visual arts. You hear music in whatever context it appears in, and the membrane separating those contexts is permeable. Artist-led music – famous or obscure – finds itself underscoring pictures whilst music for picture can escape into the charts and popular music canon. Was that what was going on here? Is this a deliberate attempt at a Pop Art album? Soundtracks are released as souvenirs of the films and TV shows they came from. They are enjoyed on their own merits of course, but the original purpose is never out of sight. With BBC Radiophonic Music the original application of the music was in the background, yet the way it was presented was still a kind of exhibition of applied art. The original purpose was obscured, but – as far as the BBC were concerned – the presentation was not the work of musicians, let alone artists in the conventional sense. ‘Fourth Dimension’ pushed the applied nature of the compositions even further to the background and strongly implied it should be considered critically and enjoyed uncritically, along the same lines as any other album of electronic music or even rock and pop music. Hence, I took the critical approach above and in so doing identified why I struggled to enjoy this album initially.

I would contend that all soundtrack, and music for picture, is forever linked with its original purpose. It may be hidden, but there is some permanent link, no matter how far you remove the music from the picture, which cannot be broken. Thus, you can’t ignore that entanglement when considering ‘Fourth Dimension’ alongside artist led works because not only does that context explain its flaws but it also adds to the appreciation of what you are hearing. When you consider that soundtracks created from obscure pop pieces – making these more strongly linked to the film than they would ever be to their own period’s culture – and ‘soundtracks to films that haven’t been made yet’ – i.e. artist led music in the style of soundtracks – hadn’t been thought of in 1973, the notion of a collection of title music shorn from the programmes they were written for and repackaged as pop music, when they were aping pop music to begin with… is all rather interesting and hard to pin down. Admittedly, this is still rather ersatz pop music.

The key tenet of Pop Art is the appropriation of applied arts. Although the creators of the music were involved in producing this artefact, and the BBC Records label were the ones actually presenting it, the originators were the producers of the TV and Radio programmes who commissioned the music in the first place. In that sense, BBC Records were, with the collaboration of the Workshop, creating Pop Art – of a kind. I think it’s rather more like a company selling a t-shirt with their logo on than a Warhol screen print of soup cans, but the great thing about Pop Art is that you can wear that t-shirt in a variety of contexts and the person who commissioned it unironically can be totally bemused by or ignorant of the cultural signifiers and aesthetic appreciation of what you are doing.

Sleeve Design

Andrew Prewett is on design duties and the front cover is certainly eye-catching. What is that a photo of though? I think it must be a frame of film, and the number at bottom-right is a counter. Here’s my fanciful idea: its film, taken from underneath a wine glass as it’s shattered by sound waves.

There’s a sprinkling of space dust over the image and the overlaid titles (the ITC font is called Countdown) are carefully coloured to match the diffracted lights of the main photo. But what about the size of that BBC Records logo, eh?

The back cover has photos of stop-watches to denote the fact that the fourth dimension is time. Yeah, thanks, Einstein, that’s enough concept.

The sleeve notes are quite informative and we even get a bit about the specification of the Synthi 100/Delaware, as well as photo of Paddy adopting the customary synth operator’s pose of left hand raised up to a control and right hand on, well, not a keyboard this time, but a peg in the vast matrix board.

The text by Desmond Briscoe, about the Workshop, is taken from the BBC Handbook printed every year to tell the fee-paying public what was happening to all that licence fee cash.

Multi-track Review

Scene and Heard

Scene and Heard was a magazine programme on Radio 1 presented by Johnny Moran and running from September 1967 till its demise almost exactly 6 years later in September 1973: “One hour of the latest news records, reviews and pop people talking shop”. This theme tune was introduced in 1970, replacing the previous Duane Eddy number, along with some jingles also by Paddy. Prior to joining the Workshop, Paddy had actually worked on this show in his time at Radio 1 as a Studio Manager, and we can guess that this commission was in part due to this connection.

The theme is suitably rocking and features some lovely phased drum fills and interplay between the lead synth line and twangy electric guitar. This was exactly the kind of commission that Desmond was looking for, to give the Workshop some street credibility.

Thanks to the Radio Rewind site you can hear the intro to the 5th-anniversary show of ‘Scene and Heard’ here: http://www.radiorewind.co.uk/sounds/10yrcd_16_scene&hrd72.mp3

This clip has some different Kingsland-esque music, just being used as a bed. It’s rather good, and seems to feature an actual sitar – or is that synthesized? You certainly get the idea of how Paddy’s music fitted into the Radio 1 sound.

Just Love

It’s probable that this piece was the theme to an edition of BBC Schools’ long-running “social issues for teenagers” strand, Scene. Just Love was a drama “following the romance between Ed, who has a reputation for treating girls badly, and Jenny, who comes to work in the factory canteen, and how they come to realise that they genuinely care for each other and fall in love.”

It’s an amiable waltz-y 1 minute 45 seconds that probably could have managed perfectly well as 1 minute 20 seconds. Sorry!

Vespucci

Amerigo Vespucci, who gave his name to a continent, was doubtless the source of this track title. It seems to be an altogether appropriate nod to the United States of America, given that the funk quotient is extremely high.

Laid back Vespucci was released on a split 7″ (with Scrabble, by Rene Costy) from the short-lived Dynamite Soul label in 2007. This was the first release on that label, which specialised in a series of obscure crate diggers’ favourites and shows the high regard this number has with seekers of soul and funk breaks. Vespucci is one of two tracks produced specially for the album and is probably the most wide-collared groove out of this selection. With its vaguely sitar-tinged top-line and bongo beats, the swirly carpeted world the early 70s is just a finger touch away.

A note for synthesists: this track sounds like a polysynth is being used. Check out the chords. As this was a good few years before the workshop started getting this sort of gear, we have to assume it was either a basic electronic organ being put through the filters on another synth or is the Delaware flexing its muscles? Did Paddy tune the Delaware’s twelve oscillators to simulate the polyphony (hard work if they won’t stay in tune!) A more mundane solution is to multi-track each line to build up the chord.

Update: May 2022

This update is based on information not available to me when I originally wrote this article. The sleeve notes to ‘Four Albums – 1968 -1978’ (Silva Screen Records, 2020), a boxed set of CDs with additional notes and bonus tracks for Fourth Dimension, and the radio programme The Electric Tunesmiths (1971)

I finally tracked down a file of the Radio 4 Extra show Selected Radiophonic Works presented by the Reverend Richard Coles. I was particularly keen to hear this as it contains within the programme The Electric Tunesmiths broadcast on 30th December 1971 and presented by George Luce. This is a treasure trove of lost RWS pieces and right near the end Paddy Kingsland comes along to talk about combining acoustic instruments and electronic sounds. This is a recently completed work for a BBC Schools Television programme called USA 72. Indeed the tape library confirms that this was entered into the library in December 1971. The library entry also states that this was not broadcast till the autumn of 1972, which seems a long gap. This programme was though previewed in April 1972 as part of a group of new broadcasts aimed at pupils in the 14-16 age range. This was a new requirement because the leaving age for school had just been raised with the Education Act of 1972. That would have come into effect at the start of the 1972-73 school year. ‘Out Of School’ was the umbrella name of this group of programmes, which had been broadcast since 1962 during the holidays. I think the idea was to show parents normally at work what the kids were viewing at schools and also get some extra school in for swotty types. USA 72 was produced by Len Brown and presented by Denis Tuohy, who was supposed to be the first presenter seen on BBC 2; then wasn’t due to a power cut; and then sort of was when he officially opened the station, blowing out a candle.

So, what did the producer want from Paddy? What atmosphere? They had a log talk.

“It’s not exactly a nasty piece, it’s not evil but he wanted it to be down to earth – An earth sort of thing.”

Oh-kay… No-one said it was evil, Paddy. What was that all about? Anyway.

“…he wanted to use electronics sounds – but he also wanted to use real musicians – he wanted some percussive effects with conventional drums and percussion going on behind.”

Fine, so this will be right up Paddy’s street. But how did he go about composing that?

“Started off at the piano – thinking up ideas and chords and just playing around”

Of course! What about that percussion though? Off to “the studio”. Well, we hear that beat first. A funky beat! Then he adds guitar. It’s Vespucci (if you hadn’t already guessed)! Next, it’s back to “the Workshop” and the synthesizers are laid down. Three tracks. It’s very clear from this that he is adding the chord notes one at a time, as I surmised previously. Three tracks to play the triad chord. Moreover, in his notes for ‘Four Albums 1968 -1978’ Paddy confirms that all the chords were built up line by line. I almost think he was answering my question! Maybe… And finally, the tune is added on top.

It’s clear that this is not the version we hear on Fourth Dimension though. As noted above, many of the pieces were reworked for the album. I assume this was particularly needed once John Baker dropped out and what we hear on The Electric Tunesmiths is only 3-35 seconds long. The new version is certainly better produced, but it’s not clear if the whole thing was re-recorded or he reused the backing. The bass and drums sound more or less identical to my ears. The lead synth melody was definitely redone and sounds much more refined. A couple more years playing with synths obviously helped. In fact, the solo was played by none other than John Baker! A revelation indeed! So, was this done before he dropped out and is that photo of the two colleagues at Delaware, with Baker sat before the keyboard, from that very session?

I should also (rather awkwardly) point out that, as well as that nugget, in his notes for ‘Four Albums – 1968 – 1978’ (2020, Silva Screen Records) Paddy says that the music was for “an episode of USA 72, a documentary on Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci”. I’m not sure about that. As there aren’t any other pieces in the tape library I assume this was the only piece for the series. Luce states that this: is “an introductory piece”, meaning I take it, the sig tune. The episodes are on New York, Detroit, North Dakota, Mississippi and California and Paddy says it shows “a bit more of the side of America we don’t usually see”. Furthermore, and to make this official, the 1972 BBC Handbook has this to say: “USA 72 was a new geography series for the 13-16 age range consisting of five documentary films specially shot on a wide range of locations across the States“. The memory plays tricks, but maybe there was more about Vespucci the explorer in this series than is made clear in the scraps of information I’m been able to find.

Reg

Reg was written for the BBC African Service but is better known in record collecting circles and Dr Who fandom for being the B-side to the Doctor Who single RESL 11. We’ll take another look at this one in the Doctor Who part of the review, but check out the bongos on the intro which also turn up on The Changes. The rest is toe-tapping current-affairs pop.

Tamariu

Tamariu is a lovely spot in the Costa Brava, apparently. The track is a “for BBC TV” number – a wistful sort of a tune which would fit into any number of situations.

For some reason, the only tape copy appears to be in the Delia Derbyshire tape archive held at Manchester University. There isn’t one listed in the (currently available) Workshop archive catalogue though, which makes its origins harder to trace. Maybe she just liked it.

One-Eighty-One

It’s another funky beat! But what was that doing on Radio 4? No clues, but Paddy was churning out stuff for Radio 4 so it could be for any number of possible programmes listed in the archive – or something that’s not even in the archive because someone borrowed it! (see previous).

As well as being selected for the test card tape (see above), this track had a strange second life as music to an obscure computer game called “Space Funeral”

“Man, this game was weird as hell. It seemed more like a broken art project than a game, convoluted and strange.”

Fourth Dimension

We’re now on side 2 of the LP and making a strong start with this extended theme for BBC Radio 4 children’s’ show called, wait for it, 4th Dimension. This compendium programme featured all sorts of stories, drama, comedy, quizzes and games, as well as features on the usual things that sensible Radio 4 listening kids wanted to hear about. Of course, that included an item on 7th July 1973 with Paddy Kingsland “who composed our signature tune, talks about that and other radiophonic music of his, now released on a BBC LP – 4th Dimension (sic)”. If only I had a tape of that edition! The show visited the Workshop again in 1975 (and who doesn’t want to hear that too?) and in late 1973 ran sci-fi serial Duke Diamond with “Radiophonic special sounds and music by Dick Mills”. Hopefully, there’ll be a bit more about that in a later part of this review series.

This is the album title track and the subtitle is ‘and other synthesizer music from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’ – which implies they expected you to know what this was from then, even if its origins are more obscure now.

Colour Radio

I think I’m guessing right that this was for a programme called ‘Local Colour’ which was made by BBC Radio Leeds. It certainly has the whimsical character of light and local programme for radio, so it figures. The Workshop tape library firmly states it as Colour Radio in 1972, but I’m seeing Local Colour in the BBC handbook a few years later. Answers on a postcard, please.

Take Another Look

We ‘re off for another waltz, with the theme for “Take Another Look”. This programme’s hook was “Unusual filming techniques reveal a very different world from the one we think we know.” Eric ‘Magic Roundabout’ Thompson was the narrator for a bug’s eye view of the microscopic world.

Kaleidoscope

Kaleidoscope was a daily arts and science (later to drop the science) slot on weekday evenings on Radio 4

A bass guitar picking out a rhythm and laying down the harmonic progression is joined by a simple ‘Up’ arpeggiator, sounding a lot like a Casio VL-Tone*, which is joined by a single digit synth line. If it had stayed with that and added some electronic percussion, he could have stolen a march on a lot of synth-pop to come. Instead, we’re in 3/4 time and a sedate waltz takes shape as more synth lines are layered up. It doesn’t really go anywhere and this is where the cracks caused by producing a whole album in a hurry really start to show, I’m sorry to say. But at least it’s short.

*see Da-Da-Da by Trio, seven years later.

The Space Between

You may remember that the first track on The Radiophonic Workshop album was written especially for a Radio 3 programme showcasing the Workshop, called ‘The Space Between’. Paddy’s contribution to that show was apparently a piece called ‘The Blue Light’ and was probably (given the theme for the other contributions) based on the Brothers Grimm story about a soldier being granted wishes, getting his revenge and taking the throne.

The music doesn’t seem to fit this story at all and is more reflective and wistful than magical and vengeful. To add to the confusion there is a tape in the archive called “the blue dot” which is credited to Malcolm Clarke and Glynis Jones. That may have been some other in-joke though. As no recording of this programme exists in the public domain I’m not sure how this track fitted in.

Flashback

The other track newly composed for the album, Flashback certainly got about a bit. First to snap it up was the Open Golf Tournament in July of 1973. A year later it was the soundtrack to Wimbledon and a few months after that it was used in truncated form for early-evening BBC2, Robin Day helmed, proto-Newsnight, err, news programme, err, ‘Newsday’ (geddit?).

Here it is – in updated form – in use in 1975:

Later it was re-fashioned into a ‘Herb Alpert’s Newsround’ jazz ensemble piece and you can hear that thanks to those nice people at TV Ark (or you can when they come back on-line)

http://www.tv-ark.org.uk/mivana/m.php?p=bbc2_newsday_171077&spl=1

It seems that a version was considered for release at some point in 1974 as the Radiophonic archive tape entry (reference TRW 8044) is called “Flashback for Newsday Disc” and produced for BBC Enterprises’ Jack Aistrop. In any case, it wasn’t released and there are no suspicious missing catalogue numbers from late 1974, when Newsday was launched. However, there is quite a bit of a gap between releases from RESL 23 – The ‘Forsyte Saga/The Onedin Line’ – in September ’74 till RESL 24 ‘The Janes, The Jeans And The Might-Have-Beens/Adios My Love’ in May ’75. Who knows what happened? Please write in if you do! (*cough* Tim Worthington *cough*).

Sources

- http://www2.tv-ark.org.uk/testcards/bbc.html

- BBC TV TEST CARD MUSIC: A personal view in three parts by Paul Sawtell A.M.B.I.I. M.P.A.

- Music and the Broadcast Experience: Performance, Production, and Audience

- Astronauta Pinguim blog – Five questions to Paddy Kingsland

- Uncut magazine interview with Paddy Kingsland

- The lost geniuses of library music – the Guardian

- The Ransom Note Interview with Paddy Kingsland

- http://www.broadcastforschools.co.uk/site/Scene/Just_Love

- 4th Dimension – Genome

- Selected Radiophonic Works

- The Electric Tunesmiths

- The Leaving of School Age Order 1972

- Out of School – 5th April 1972

- https://worldradiohistory.com/UK/BBC-Annual/BBC-Year-Book-1973.pdf