Contents

- Introduction

- The World of Dudley Simpson

- Band with Brothers

- More Dudley

- Moonbase 3

- The World of Doctor Who

- Collector’s Corner

- Closing sting

- Sources

Introduction

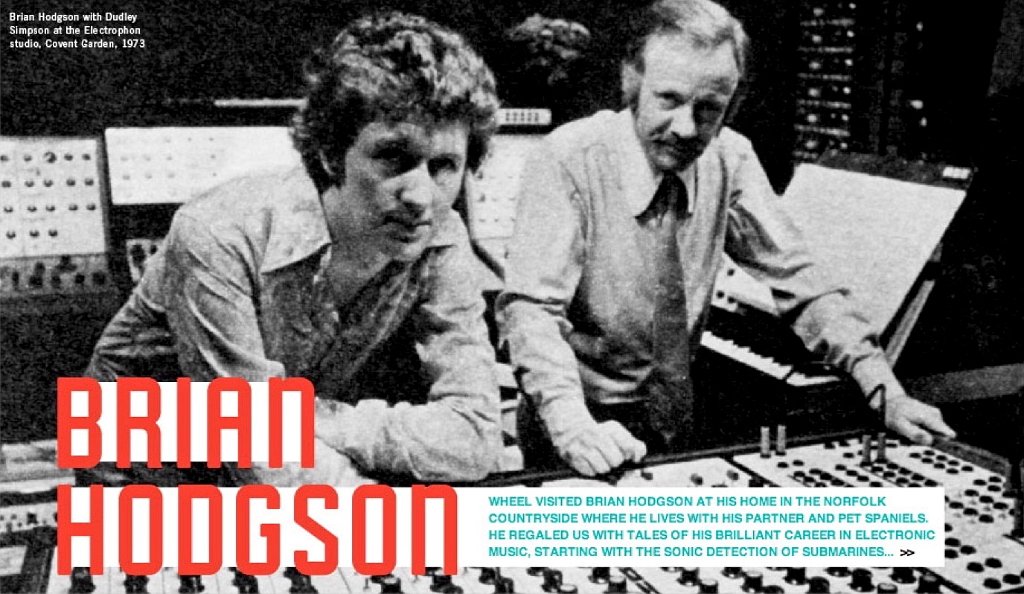

This second part of a review of releases related to Doctor Who (DW) at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop (RWS) on the BBC Records label is all (and I do mean “all”) about probably the most obscure release in that category. ‘The World of Doctor Who’ is on the flip-side of another obscurity, rendering it almost invisible to all but the dedicated fan. It is, however, also the most visible sign of what is one of the most important chapters in the story of DW and the RWS. It’s not a landmark, like the original theme, which is arguably the most important single thing the RWS ever did. It is a milestone though. A marker of a significant change and the beginning of something new. Along the way we’ll take in: a truck full of explosives exploding; career advice from Dame Margot Fonteyn; a digression into Russian gymnastics by way of the Welsh Guards; Stanley Kubrick speculation; the man who sold his wife’s tiara to buy a computer for his home studio; what a Putney and a Cricklewood are; Panopticon VII, some mild teasing of Decca records and generally take wander all over the late-sixties/early seventies TV music and synthesizer scene.

So, with much more ado before getting into the 7” single which is to be the main subject of this part Discographic Workshop, we need to introduce a major character in the story of DW music and the RWS, Dudley Simpson.

The World of Dudley Simpson

Who’s Dudley Simpson?

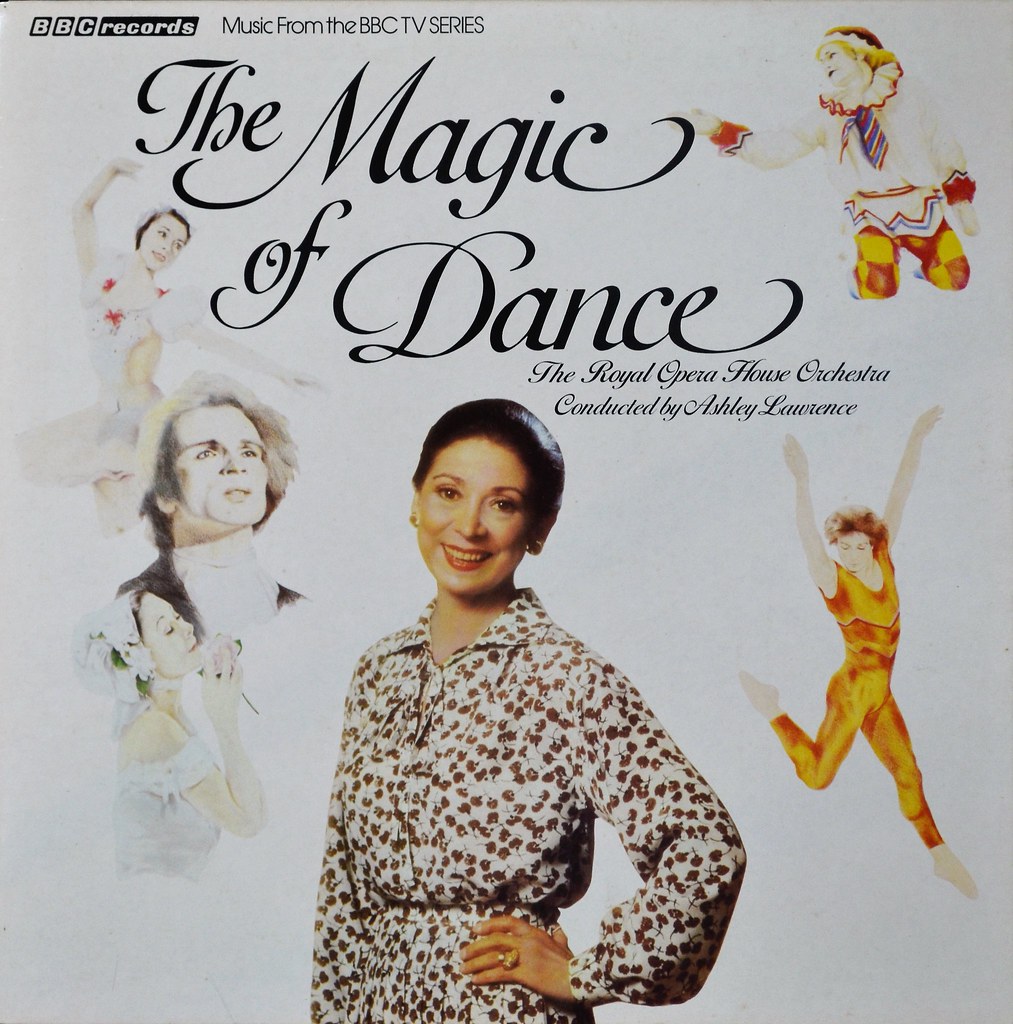

Dudley Simpson was born in 1922 and raised in East Malvern, Melbourne Australia. Starting aged four on his grandpa’s piano, by 16 he was working as an accompanist for radio stations. The second world war interrupted his playing and almost curtailed it permanently when his hand was injured when a truck he was driving was bombed. If I tell you the truck was also full of explosives you can appreciate what a lucky escape he had. He was able to get his fingers moving again playing concerts organised by an American comrade. After the war, Simpson attended the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music and completed a diploma in music. From there he started work at the Borovansky Ballet as a pianist and assistant conductor rising to the position of musical director by 1957. When Dame Margot Fonteyn visited Australia, she suggested that Simpson come to London, which he did, and his career took another step up. He landed a job conducting at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden and toured Europe with the Royal Ballet. He was also Dame Margot’s musical director.

Your name’s not Bruce, then?

At this point, you’d be forgiven for wondering how this clearly very talented classical conductor with a successful international career, came to be sitting in a room at Maida Vale with Brian Hodgson, hoping a primitive synthesizer wouldn’t go out of tune.

Simpson was becoming bored with conducting and was keen to get into composing. By 1960 he was married and with a family on the way he wanted to make his earnings more secure. He was also an Aussie in the heart of London’s classical music scene. He might well have felt perfectly at home, but there’s also a chance that he wasn’t as steeped in the culture and social cliques as his native English colleagues. Maybe a change would be less of a wrench and easier for him to affect than a native Englishman in the same position. A chance meeting with a BBC producer at an after-show party resulted in his first commission for a BBC television score. That led quickly to work for Doctor Who and Simpson eventually became a favourite of the show’s producer Barry Letts. Television music went from an occasional gig to a full-time occupation lasting until his retirement at the end of the eighties. There was more to Dudley Simpson than DW though, as we will see.

Band with Brothers

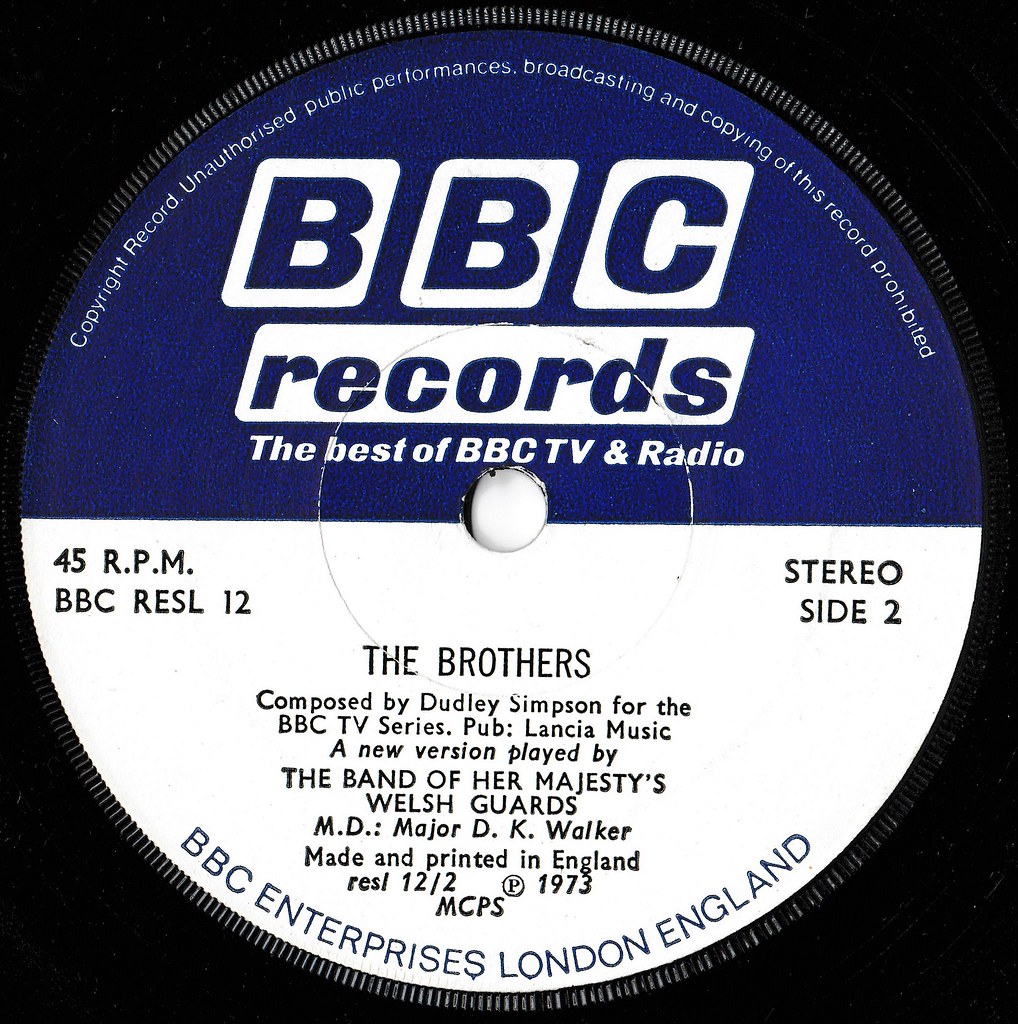

Released on the same day as the signature tune 7″ for ‘Doctor Who’ (RESL 11), the next item in the BBC Records singles catalogue featured Dudley Simpson’s theme to Sunday tea-time, family-business melodrama ‘The Brothers’. This was Simpson’s first appearance on the label, but I’m bringing it up here – a review of Radiophonic Workshop releases – because, as we’ll see with the next release, it seems like the combined forces of the RWS and Dudley Simpson had annexed the BBC Records singles release schedule for a short period in 1973. The additional fact that hapless, short-lived sixth Doctor Colin Baker starred in Brothers, is presented in further mitigation to charges of getting way off the point.

Speaking of getting way off the point (but to the point of the sub-heading above) this version of the theme to ‘The Brothers’ was performed by The Band of Her Majesty’s Welsh Guards and was the B-side, wait, no, Side 2 of ‘March of the Champions’ (RESL 12, 1973). The single was a promotion for the guards’ LP ‘Friday Night Is Music Night Presents… March of the Champions’ (REB 154) and the A-side, damn it, Side 1(!) was written in tribute to the ‘sparrow from Minsk’ herself, gymnastic sensation Olga Korbut (although she looks slightly too tubby on the sleeve illustration by Andrew Prewett). I have searched in vain for any connection between Korbut and either DW or the RWS.

More Dudley

‘The Brothers’ was typical of the kind of show which Simpson was writing music for at that time. Starting with TV movie ‘Jack’s Terrible Luck’ in 1961 and ending with ‘Tales of the Unexpected’ in 1988, he composed for around sixty different shows, including Doctor Who. Sometimes it was just title music. The Brother’s seems to have been his first of those and he went on to provide the themes for ‘The Tomorrow People’ (1973), ‘Metamorphosis Alpha’ (1976), Target (1977) and ‘Blake’s 7’ (1978). Occasionally his conducting skills were all that was called for, but incidental music was his forte and you could hear his music any day of the week. For example ‘The Wednesday Thriller’ and Thursday Theatre (both 1965). From classic stories – Lorna Doon (1963), Sense & Sensibility(1981) – to cutting edge sci-fi – Out of the Unknown (1965, 66 & 71) – and thrillers – Paul Temple (1971) – to children’s – Supergran (1986) – Dudley Simpson had three decades of success on British TV before his retirement.

Doctor, Who’s Dudley Simpson

Dudley Simpson was one of the RWS’s only regular collaborators. Starting with Brian, continuing with Dick Mills, and occasionally others too, he came into the Workshop to finesse his DW scores with Radiophonic embellishments. As we will see (when I finally get to the record I’m supposed to be reviewing) for a period he was solely using the RWS synthesizers. In the

“The biggest sound for the smallest amount of money”

Doctor Who production through the sixties was not a straightforward business. Budgets were tight for what was an ambitious science fiction show and the BBC were often unsure if they wanted more of it, or less of it, or none at all! Which made planning and budgeting a challenge. The theme music was simply great, and the sound effects from Brian Hodgson were more than adequate, they were often stunning and even became the music for a spell when the music budget was challenged to not exist at all (which is another story. I have a lot of other stories). As the theme and ‘special sound’ were from the RWS they came all but free to the DW production. Their costs were counted as below the line, literally the line dividing the ‘talent’ from production staff on the budget sheet. Any composer’s services would be paid ‘above the line’, as their credit would be amongst the actors and writers etc. who were paid a negotiated rate for their contribution, not a salary. Everyone who worked for the BBC was below the line and once they were signed up for the programme the costs for their time were taken care of. Hiring a composer, and the musicians who played the score, were firmly above the line and the budget was consequently far more tightly constrained.

Speaking to Mark Ayres, Simpson laid out the reality of BBC budgets.:

“You see, the music came as the last item in the budget. They made it quite clear to me that if we were going to have music at all it had to be done on the cheap. And, of course, the Radiophonic Workshop – those boys are all producers and they’re on BBC producers’ pay. I was the only one who got a fee out of it for my time spent there. So it was Barry Letts who said to me, “You’d be just the man to create it and help save the money.” So I did what I could”

‘Notes from a Large Island’, Doctor Who Magazine Special Edition #41, Autumn 2015

His “time spent there” refers to the hours he put in at the Worksop. Simpson’s working arrangement with the Workshop was almost unique. It was all but a closed shop. strictly invite only, with other artists who did get in generally being of the more avant-garde, sound-art type. Simpson was the exception, but this was not a permanent arrangement and it went through several phases during his tenure on DW. The attraction of Dudley Simpson for DW was that he could bring the goods on such tight budgets. As Mark Ayres puts it “The biggest sound for the smallest amount of money”. This meant using the same musicians to over-dub their parts, using musicians who could play different instruments in the same session, scoring for instruments (and thus musicians) with a wide range so they could fulfil many parts, using keyboard instruments he could play himself, and having the will and the wit to use the RWS too.

The Sixties

Simpson got started with DW late in 1964 scoring series 2 opener ‘Planet of Giants’ (using big instruments for the giants against small instruments for the heroes – so simple, so effective) and then ‘The Crusade’ and ‘The Chase’. Series 3 only had one score from Simpson ‘The Celestial Toymaker’. For series 4 he was back up to three scores with ‘The Underwater Menace’, ‘The Macra Terror’ (‘Chromophone Band’, realised by Delia Derbyshire) and ‘The Evil of the Daleks’ (made using the basic test oscillators at the Workshop, just like Derbyshire’s theme). Series 5 features two Simpson scores, ‘The Ice Warriors’ (ethereal female vocals, “Who’s Ethel Reel, Dudley?”, quipped Dick Mills, whenever Simpson used this description) and ‘Fury from the Deep’ (using test oscillators and distorted piano). Series 6 saw an unbroken run of three stories with ‘The Seeds of Death’(piano and percussion with echo and other effects processing), ‘The Space Pirates’ (Ethel Reel on vocals, again) and ‘The War Games’ (pipe organs!) all with his music. The short, four-story, series 7 boasted two of Simpson’s compositions ‘Spearhead from Space’ and ‘The Ambassadors of Death’ (spy jazz-rock, space ballet and harpsichord!). The level of sophistication was improving with the available technology, so the next step was a natural one.

Throughout these first six years, there were no synthesizers at the Workshop. Simpsons pre-recorded scores were variously treated with tape and other effects available at the time. Some would say that this late sixties was a creative peak for Simpson with his most catchy (if that’s the right term) cues. Mark Ayres has pointed out that this was in part driven by the difficulty of doing what they wanted to do with the limited equipment available. They were experimenting. Both the RWS and Simpson were stretching what was possible and being inventive out of the sheer necessity to match the imagination of the DW scripts. On the other hand, ‘Ambassadors…’ was the last score recorded before he saw anything but a script. This meant that the music was driven purely by what was imagined. ‘The War Games’ was written almost without a script at all. It’s worth pondering whether the combination of equipment more suited to the job and seeing the images subtracted from the result somehow.

The Seventies

In series 8, which started production in 1970, Simpson took on almost all the incidental music for DW. This is also when the synthesizers arrived at the Workshop and, for this series only, it was the sole instrument he used. That’s the one we’re really interested in here. If you recall there’s a record to review at some point, which has elements from this era, but I’m not ready for that, just yet.

Timecode Lord

Another innovation for the soundtrack to series 8 was the introduction of timecoded video-tapes. Simpson was proud of this innovation claiming it was done specifically for him to compose to. In the early days, all the incidental music and sound effects were written based solely on the script. Then it was recorded to tape and cued in with the actors during the studio recording. As post-production was introduced, where the sound could be mixed after the performance was on videotape, it became easier to time all the music cues and sound effects to the action, and that’s what Simpson did. This facility, which is the norm now, tended to push his compositions towards a more conventional approach. It also could be over-done from time-to-time, with this Mickey Mousing (meaning matching action to music or vice versa, a la early Disney films, not necessarily for comic effect, although…) occasionally creating unintentionally over dramatic punctuation (he’s pouring himself a coffee!!!) or jarringly humorous interjections (Wah, wah,

Even More Dudley Simpson, & Horror

I’ve already spent too much time getting to ‘The World of Doctor Who’ and there’s still the matter of another BBC sci-fi show to go through yet. Needless to say, there is a lot more Dudley Simpson music for DW that could be covered here. ‘City of Death’ was a high-point of the later period of the fourth Doctor. The romantic theme with the Doctor and Romana (Tom Baker and Lalla Ward, at that time a couple) capering around the cobbles and cafes of Paris is particularly beautiful. He was also there right through some of DW’s most purple patches. The gothic horror era of the mid-late seventies is particularly strong, albeit a bit too strong for a lot of younger viewers, and is all served well by Simpson’s music. We will hear a bit more of his work when we get to ‘Genesis of the Daleks’ (REH 364) in the next part of Discographic Workshop.

A Reel Shame

Regretfully, (or mercifully, if you’re trying to write up a summary) most of the tapes of Simpson’s music for DW are missing, presumed lost for ever. The BBC simply didn’t keep them and Dudley’s composer copies appear to have been mislaid during one of his moves. He probably never imagined that the Beeb would be so careless as to lose the originals. When Delia Derbyshire’s archive was catalogued after her death, a reel of his ensemble’s recording for Series 10’s ‘Carnival of Monsters’ (1973) was found, but without the subsequent Radiophonic overdubs. Other odds and ends were kept at the Workshop, often on the sounds effects reels, which were always preserved for future use. Paddy Kingsland helped Simpson with the synth over-dubs for ‘The Sun Makers’ (series 15, 1977) during Dick Mills holiday and kept a copy simply because he assumed that it was standard practice.

End of the Delaware (Road)

The relationship with the Workshop was a strong one that Simpson valued enormously. Workshop boss Desmond Briscoe was a bit miffed when he felt that their Aussie pal was given all the attention in the 1973 Radio Times Doctor Who Special though. He was actually more wound up that no-one had thought to ask them for a piece about how to make the infamous voice accompany an article on making your own

Eventually, though Simpson was locked out of Maida Vale and left to his own (electronic music) devices. This came about largely due to Brian Hodgson re-organisation of the Workshop and the dismantling of the already antiquated Delaware synthesizer. ‘Buy your own synth, Dudley’ might have been the message.

Simpson continued writing and recording DW music until ‘The Horns of Nimon’, which was the last story of series 17, right at the turn of the decade. By now he was relying on other means to get the electronic elements he craved, it wasn’t the same though.

Epitath

One DW story from the seventies that Simpson never got to write for was the abandoned (due to industrial action) ‘Shada’, from series 17. In 2017 a completed Shada was pieced together from (mostly location) footage that was filmed at the time and animated inserts with voices by the original stars, Baker and Ward. Simpson’s mentee Mark Ayres wrote an original score which skilfully pays tribute to “the guv’nor’s” style. Ayres employed session musicians, an EMS VCS3 (borrowed from Paul Hartnoll of Orbital), a Yamaha organ (a YC-45D, reconditioned by himself) similar to the mighty EX-42 that Simpson used and even

“Composer Dudley Simpson was one of my earliest inspirations. Later mentor and friend. My score for Shada is a bit of a love-letter to this period and particularly to his music. It was poignant and heart-rending that he died just as I finished work on it. RIP Dudley”

https://twitter.com/MarkAyresRWS/status/943950700496683010?s=20

Moonbase 3

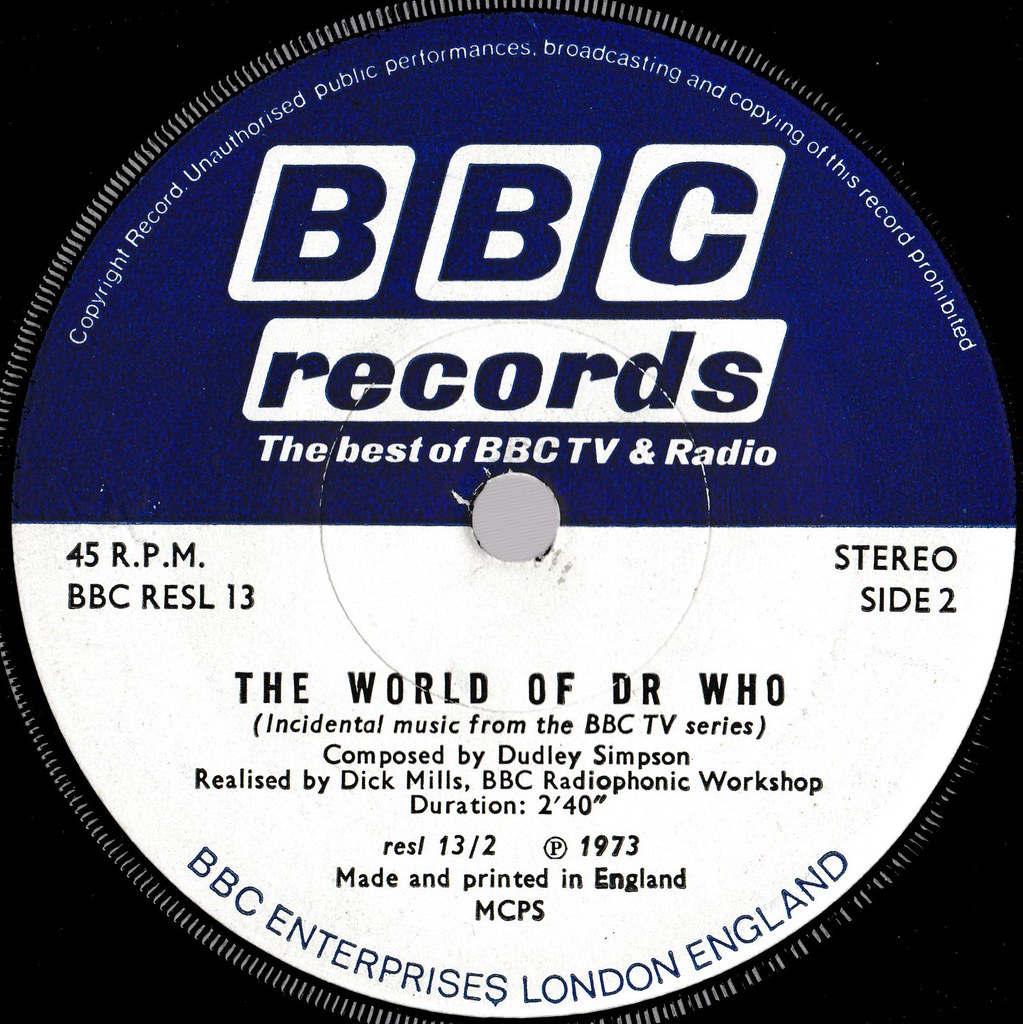

In September of 1973, mere months after the Doctor Who theme was released by BBC Records as a single, fans were in for another treat. A second, Who related single, was in the shops (if you were quick) and this time it was Dudley Simpson collaborating with Workshop stalwart Dick Mills. It also sported the same blue and white label more common on the LPs, but alas, no picture sleeve.

Like Doctor Who, but less exciting!

I’m not sure if that was the pitch they used, but it might as well have been. Moonbase 3 was the brainchild of DW’s sometime producer and script editor, Barry Letts and Terrence Dicks. If DW could be described as ‘a bit daft’ and ‘a show for kids’, ‘Moonbase 3’ did away with those ‘problems’ and instead put budgeting head-aches and petty bureaucracy at the core of their sci-fi show for grown-ups, set in a near-future moon colony. Where did they get their crazy ideas from? (Dealing with budgets and bureaucracy whilst making a TV show about (quite often) moon colonies, perhaps? Just a thought). Sadly, for them, it wasn’t a hit and after the first six episodes, a further six they had anticipated were not made. It was left to those swanks over at ITC to bring on their brasher ‘Space: 1999’ a couple of years later to show how it (i.e. moon-base based action) was done (i.e. ‘

Artificial Gravitas

Nonetheless, Simpson did the business with his theme for the Beeb’s lunar excursion, providing a serious tune with plenty of gravitas (useful on the moon) and portent. Probably on a very reasonable budget too. BBC Records were hoping that the enthusiasm for sci-fi and Dudley Simpson would translate into some sales so this single was produced, but it was not to be (see below). Brass is to the fore and timpani adds the necessary drama. Dick Mills is credited with ‘realisation’ for ‘Moonbase 3’ though, and that’s down to the synthesizer phrases. These parts, probably played on the mighty EMS Synthi 100 ‘Delaware’, appear throughout, both in underscore and taking the lead. There’s also a siren-like line which closes the whole piece and works almost like a sound effect, settling the viewer in for the experience of life on ‘base’. “Blasted alarm’s gone off again. When will they get that fixed, do you think?”. “Have you seen the latest budget from maintenance?” etc. With Moonbase 3, it was business as usual for Simpson and Mills. Dick helped create a suitably spacey sounding patch on the synth with input from Simpson, and then the composer played it along with the pre-recorded orchestra, over-dubbing. Mills would have engineered this whole session, giving him the ‘realisation’ credit. We’ll nip back to MB3 later and see what happened to the title music after this single was released… (hint: Dudley and Dick did not make an appearance on Top of the Pops. Imagine that though! Dudley conducting a small ensemble whilst Dick wrestles with a VCS3)

The World of Doctor Who

Short & Suite

The ‘side 2’ (got it!) to RESL 13 is also a Dudley (composer) and Dick (realisation) collaboration. ‘The World of

In practice, this Gallifreyan gallimaufry (ahem) is a spliced together selection of Simpson’s DW incidental music with added Radiophonic sound effects. At 2:40 it’s a brief visit to the world of DW, but a welcome addition with plenty to chew on.

Many World Theories

I think it was the physicist Richard Feynman who said that anything is interesting if you look closely enough at it. Whether you can persuade anyone else it’s interesting after all that examination is another matter. With that in mind, I was surprised how much I was able to find to say about ‘The World of Dr Who’. What follows can be filed under speculation in many cases, but I hope that it is at least interesting speculation, based on solid facts.

Worlds Title Holder

This DW ‘World’ is not the first one that BBC Enterprises and the RWS had thought of visiting. As far back as 1967, the BBC’s commercial arm was in meeting with CBS Records and the RWS about various projects, including a DW stories EP. That did not work out, so in 1968 they tried again with The Kinster Company and MGM. A plan was hatched with DW producer Peter Bryant for up-to 5 records of DW fun and adventure. Alas, Bryant became too busy making DW and then MGM lost interest too. However, now that the BBC had its own record label, including the Roundabout sub-label, aimed at children, another attempt was made as ‘Radio Enterprises New Project no. 21’. This release was provisionally titled ‘Sounds of The World of Doctor Who’. (Aaaah!) By April of 1969, it had been confirmed that Decca’s rights to the theme tune had expired (hooray!) and someone had probably realised that the ‘world of’ heading was being used in a series of low-priced compilation records by, err, Decca! Now retitled ‘Dr Who’s Diary’ the story-based record was discussed further, but never carried forward. Maybe River Song didn’t want it published, eh fans!?

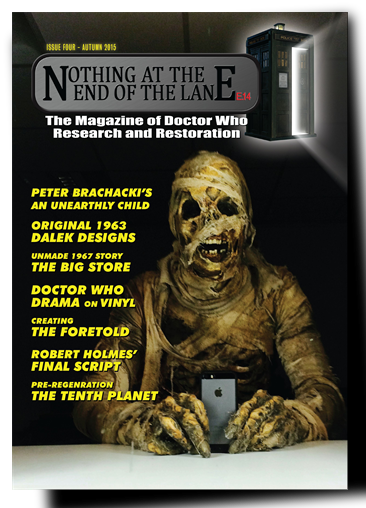

[I’m grateful to the researches of ‘Nothing At The End of the Lane’, the DW research magazine, for the details of the foregoing story. Any mistakes are my own].

Nevertheless, the ‘world of’ title was evidently still in someone’s mind when this suite was prepared. Why would that be? I mean, apart from being a perfectly sensible way to describe a medley of DW hits. A cheeky two fingers to Decca, perhaps? Honestly though, was that really a consideration? Who cared enough? Well, the BBC may have been having an in-joke about the fact that Decca took the ‘world of’ idea that had been the first title of the story record, but that’s all a bit tenuous. There are a few slightly odd things about this ‘World’ though.

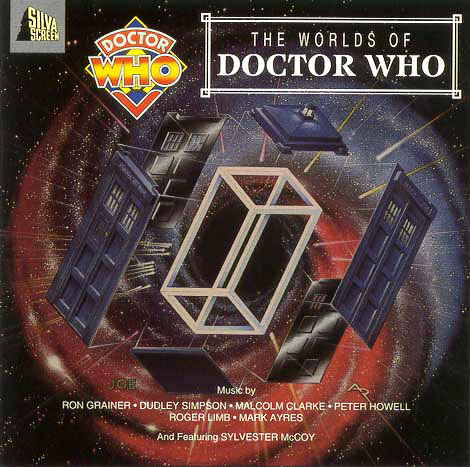

The Best of All Worlds

One apparently pedantic point is that in the RWS tape library document (available at Ray White’s whitefiles.org) the reel for this release is called ‘The Worlds of Doctor Who’, not ‘World’. It seems like a typo happened somewhere because the suite, and the whole premise of the show implies worlds, not a world. On the other hand, the Doctor’s entire story-world is distinct from our own. A CD called ‘The Worlds of Doctor Who’ was produced for Silva Screen by Mark Ayres in 1994, so either way works, it’s just that someone at BBC Records seems to have preferred the singular to the plural.

B Move?

Another slightly curious thing about ‘The World of Doctor Who’ is that it wasn’t the B-side (alright, Side 2!) to the theme single. As we saw in the last part, Paddy Kingsland’s track ‘Reg’ was used instead. There were good reasons for that choice, but this piece seems better suited. Well, maybe, but ‘The World of…’ was put together after Moonbase 3 was already complete, and some 9 months after the theme single was finished. There was no thought of creating the DW suite until the ‘Moonbase 3’ single came along, and then it was for very specific reasons which were not really about DW, as we’ll see. At least this way round dedicated DW fans, keen for any related material, would have bumped up sales of ‘Moonbase 3’ and the two records make a nice pair.

Contracted Out – Of Existence

Still though, why this choice at all? Why not something else from MB3 or more complete pieces of Dudley’s work for DW? At Panopticon VII Simpson and Mills explained another reason why (as well as the tapes being junked), outside of the series 8 synth scores, none of Simpson’s incidental music for DW had been released. The small ensembles that Simpson used were only contracted, by him, specifically for the purposes of recording the soundtrack to the television programme. The playback of the tape for the show’s recording counted as a performance. Such were the strict rules of our old friends the Musician’s Union and the limited contact that Simpson used to keep the costs at rock-bottom. In a sense, they were treating the music as live performance, even when it was being played back, to avoid the publishing rights that would have made the music less economically viable. Any further use of that recording was thus not legally allowed without gaining all of the performer’s permissions and agreeing on appropriate payment. Apparently, it was never worth the effort to go back and update the contracts and as time passed it became almost impossible. Right and proper for the fine musicians, but rather a shame for fans of the music. This might explain why the tapes were not kept. Once the programme was made, they were simply not reusable.

A female Doctor?!

When the Moonbase 3 single was slated for release, BBC Records imagined that, as they’d sorted out the contracts for the use of the theme, they could use another Dudley Simpson piece for the B-side. “They wanted something of DW off the same band”(sic) agreed Mills and Simpson at the DW convention. This is not an unreasonable request. If you look at BBC Records’ theme singles, the b-side is usually a piece of incidental music from the same programme, recorded as part of the same sessions as the theme. Often it’s a softer and slower female character’s cue, called something like ‘Agatha’s Theme’, ‘Samantha’s Lament’ or ‘The Dutchess’s Bolero’. Typically, and much to the labels’ producer Jack Aistrop’s dismay I imagine, Simpson never used “a big band like that” for DW, or probably MB3. They would have pushed the boat out for the title music, of course, in a break from the economy of regular scores. Hence, there was nothing under the existing contracts available for Side 2. No ‘Dr Helen Smith’s Theme’.

Library Music

Realising that there were Simpson originals in the RWS tape library, a solution was found. They would work something up from whatever was available under Simpson’s contract, meaning anything he alone played on and, whilst Dick Mills already had a credit for Side 1, it made sense for him to ‘realise’ this medley. That said, there is live instrumentation on the record. The only explanation I can offer for that paradox is that all the acoustic instruments as are used as backing. Whether this is a real reason why they could be used or there is some other story. I really cannot be sure.

Dick & Dudley’s Zoo

That brings us to the contents of ‘The World of Doctor Who’. The suite comprises three main parts, the first being, erm, don’t know. Wait! What?

The first thing you hear is a blast of brass with a Theremin-like, descending warble. The warble is characteristic of the Theremin’s ‘hands-off’ interface and is almost a throwback to 1950’s Hollywood, b-movie sci-fi. In reality, the sound could have come from any of the EMS synthesizers available at The Workshop. As we don’t know when this part of ‘The World of’ was created it’s even harder to guess what synth was used. The joystick controller (repurposed from model aircraft radio-control units) featured on most of the EMS synths can easily stand in for the arm waving involved in operating the Theremin. This type of sound can also be set-up as a ‘patch’ and played from a keyboard, but the joystick is more immediate.

Coming out of the opening flourish, we can hear a menagerie of wild alien beasts from Dick Mill’s private zoo (or sound effects library, you’d have to ask him yourself), conjuring up the scene of a cautious trek through a dangerous space jungle. Musically you have a very simple one-note electric guitar riff with barely audible woodwind (synthesized, or real? You decide!) in a very low register, accompanied by more synthesizer warbles. It’s a tension builder, almost so generic you feel that you must have heard it somewhere before. Plenty of people will tell you confidently that they have heard it before and that it’s music and sound effects from, say, ‘Planet of the Daleks’. They are wrong though (sorry!). I bought and watched that story on DVD for research (and entertainment!) but there was no trace of that guitar picking and the beasts sound wrong too. Neither is it from other suggestions, ‘Carnival of Monsters’ or ‘Frontier in Space’. I have asked the best experts available and it is of unknown provenance. If you do know where in the world of DW it was used and can prove it with a clip, please get in touch. After forty seconds of this mounting anxiety, the uneasy guitar changes up a key and there’s almost a hint of a tune from the synth before a brass swell announces the villain of the piece.

Doctor Who, Or how I learned to stop worrying and love the synthesizer.

“You wanted to know how long I could hold out against that machine. The answer is, I can’t”

The third Doctor in ‘The Mind of Evil’

Well, the synthesizer was a hero to some and a villain to others, especially back in the seventies. I’m looking at you Musician’s Union. With some prompting from Brian Hodgson, producer Barry Letts, who was very keen on new technology in TV production (see the Timecode Lord section above), was quite excited by the potential of the first synthesizers to arrive at the Workshop and he asked Simpson to create an all-electronic score for series 8. Letts was by this means also able to cut the music budget, which was handy as the show now being in colour was adding to the budget problems. You can see why this would excite him! Some of the

Simpson took the not unreasonable view that as a classically trained composer he would treat the synthesizer just like other instrument and write a score for it in his usual way. You have to realise that this was a significant albeit inevitable departure from both what had come before in the art-form, or even been possible. It’s also not what the makers of that synthesizer had originally envisaged. Having no obvious way to play it musically was the most obvious clue to this worldview. But what was this synthesizer and where did it come from?

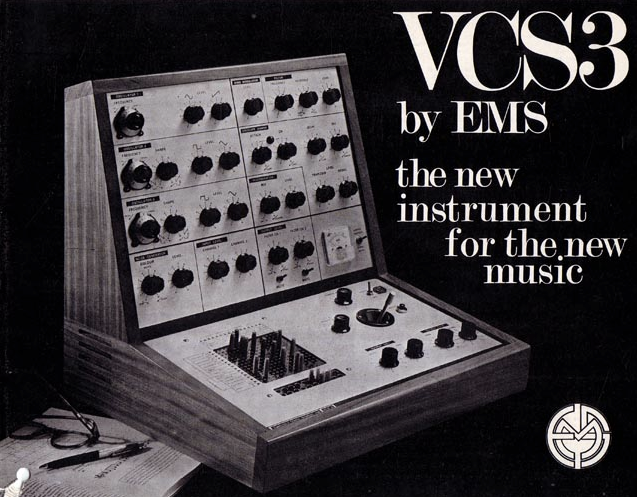

EMS

Electronic Music Studios (EMS) was the company responsible for Europes’s first commercially available synthesizer, the VCS3. It’s also an instrument with a claim to being the first portable synthesizer in the world, beating its American counterpart the Minimoog by a year.

Zinovieff

EMS Ltd was founded by Peter Zinovieff, who had previously worked with Delia Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson as part of Unit Delta Plus. UDP split in 1968 because Zinovieff simply wasn’t interested in making music to order for commercial clients. Daphne Oram had taught Zinovieff the rudiments of tape music (which he identified as a dead end) and he’d worked with Sir Harrison Birtwistle amongst others whilst setting up his own studio. Oh, yes, Zinovieff had an electronic music studio at home. This was not a unique situation in the sixties, but the sophistication and ambition certainly were. He had a computer. The first home computer in Britain, or maybe the world. He sold his wife’s tiara to fund all this. He was NOT messing about. The studio was mind-bogglingly complex though. Brian and Delia didn’t know what to make of it, let alone Paul McCartney, who came to visit. Even the god of Elektronische Musik, Karlheinz Stockhausen was baffled by all his gear.

Cockrell

The second EMS founder

*The Crystal Palace was the name of a contraption invented at the RWS by engineer Dave Young.

Carey

The third founding member of EMS was our recurring character, shadowing the RWS story with his pipe-smoking cameo roles, Tristram Cary. An accomplished composer of more conventional film and television scores (most famously The Ladykillers and Doctor Who) he had developed a keen interest in electronic music from the 1950s and built his own shed studio. Cary was responsible for the interface, case and look of the VCS3 as well as the user manual. After leaving EMS went into teaching where failed to influence Elizabeth Parker with his approach to the use of synthesizers whilst she studied under him. Cary’s revenge was to go to Australia and continue his fundamentalist teaching of electronic music in higher education, perhaps in return for all the excellent composers they’d sent to Britain. Sorry, I love him really. Cary’s score for DW series 1 milestone ‘The Daleks’ is fabulous.

Where’s the keyboard?

Although envisaged as a tool for teaching electronic music in schools and colleges the VCS3 was, after further consideration, augmented with the DK1 keyboard (AKA The Cricklewood, after the area where Cockrell lived) which opened it up to Dudley Simpson and other musicians, even Rock musicians.

So, with Simpson seated at the Cricklewood and Putney, let’s get back to series 8 of Dr Who and the real villain.

Master’s Piece

We left ‘The World of Dr Who’ on some sort of cliffhanger as the villain appeared. That baddie was the bane of the Doctor’s adventures in series 8, and for years to come, The Master. It’s here that we finally arrive at the nexus of this story. Dudley Simpson and Brian Hodgson were at the cutting edge, making the first ever electronic music score for television. Simpson came from the classical world and had already made a name for himself as a TV composer. Hodgson had come from the theatre world, through BBC radio drama into the RWS where he became the provider of Special Sound to DW. He was also part of the exciting milieu of electronic music in swinging London and had worked with the founders of EMS. The sixties were over and VCS3 was installed at the Workshop with our two heroes ready to start a new chapter.

The creepily ascending, whilst descending theme (or ‘cue’) for the Doctor’s arch enemy The Master was well established by Simpson from his very first appearance in ‘Terror of the Autons’, the story which started off series 8. This was a new concept for DW. With its previous revolving door of composers, no specific style or motifs were reused. Now that Simpson was writing everything he could take the idea of themes, popular in his background in ballet, into DW. It is also more efficient if you don’t want to have to come up with a new tune every five minutes.

Dela-when?

The version of The Master’s cue used on ‘World of’ is from ‘The Mind of Evil’, the second story in the series. Some have erroneously said that the mammoth Delaware synthesizer was used for ‘Mind of Evil’, but let’s examine the dates. The Delaware was delivered and installed at the Workshop between February and April 1971. Broadcast of what was the third Doctor’s second series started in January 1971 and concluded in June. Filming had started in September of the previous year. Given that ‘The Mind of Evil’ started broadcast on 30th January there’s no way that the Delaware could have been used. The available Workshop tape archive indicates that the score was recorded in September/October of 1970 which seems about right for the episodes to be fully edited. I note from the same archive that the tape for the next story – ‘The Claws of Axos’ – entered the library only in January 1971 with the transmission of that story in March.

That it was done with the comparatively tiny VCS3, is quite remarkable enough. As noted above the VCS3 wasn’t originally designed for tonal music, so getting it in tune and keeping it in that general area was a bit of a struggle. The Workshop had taken delivery of two VCS3s in the spring of 1970, mere months after the formation of EMS, and by July a keyboard had been purchased – Zinovieff no doubt already mentally spending the money on new gear for his studio. The arrival of the keyboard would have been just prior to starting work on series 8 and whilst Zinovieff may still have been confident that his studio was in the vanguard, the future direction of electronic music lay in that keyboard, and others like it.

Writing in the DW fanzine Oracle, in 1979, Philip Ince said:

“Dudley Simpson… by skilful use of a synthesiser… formed a

classic piece that [was] very evidently [amongst] the first of its kind – on television at least… Perhaps the effectiveness of these pieces can also be attributed to their being constantly repeated and linked withhorrible death, so that, when [they were] heard, the adrenaline [started] to flow in expectation.”

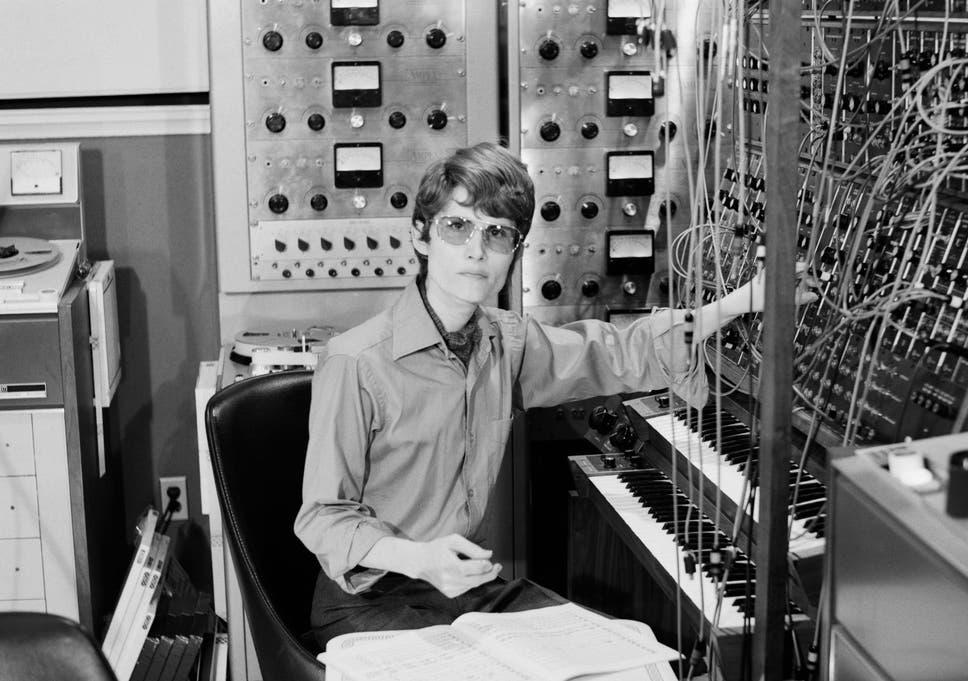

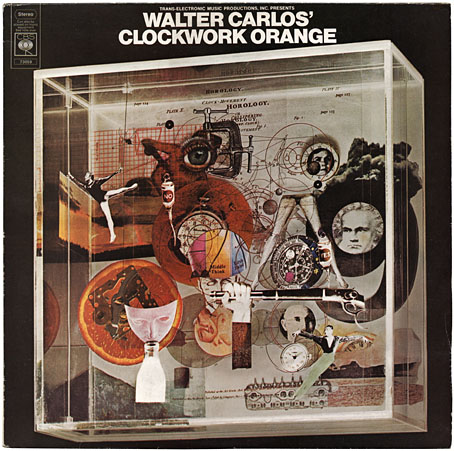

Well, quite! They certainly menace the listener with serious intent. And he’s right that this was all very new to television. After all, this was the dawn of the age of the synthesizer. Whilst the early RWS was given impetus from continental Europe’s bold and cerebral application of electronics to music, the next phase was now underway. EMS were setting the pace, but they were new-comers compared to Dr Robert Moog and the first great practitioner of the Moog synthesizer, Wendy (née Walter) Carlos. So, let’s make this

Real Horror Show

It’s perhaps co-incidence that the story of ‘The Mind of Evil’ was originally conceived by its writer Don Houghton as

And? Well, whilst I can find no evidence that Kubrick watched ‘The Mind of Evil’, it’s an intriguing notion that he was viewing DW a story about mind control, inspired by ‘A Clockwork Orange’, with an electronically realised, classical score whilst making his film. I also cannot tell exactly when he received Carlos’s tape and how that date might fit into this theory. It is fanciful, in the extreme, to think that Kubrick was thinking of putting in a call to Dudley Simpson before Carlos got in there, but maybe the DW work played a small part in ideas he was mulling at the time. And he was no doubt aware of the RWS. Kubrick’s archive is preserved and perhaps one day this theory can be put to the test. What is known is what he said to Sight and Sound magazine about Carlos’s score.

“I think that I’ve heard most of the electronic music and musique concrete LPs there are for sale in Britain, Germany, France, and the United States; not because I particularly like this kind of music, but out of my researches for 2001 and A Clockwork Orange. I think Walter Carlos is the only electronic composer and realiser who has managed to create a sound which is not an attempt at copying the instruments of the orchestra and yet which, at the same time, achieves a beauty of its own employing electronic tonalities.

Are you sure you have listened to the ‘Radiophonic Music’ album, Stanley? I mean, ‘Blue Veils and Golden Sands’ at least should make the grade. Perhaps he was thinking of electronically generated tones, not concrete techniques. To be able to convey the full range that an orchestra or even jazz ensemble or rock group could by electronic means was still very hard work at the start of the seventies though.

That Carlos’s ‘Switched on Bach’ LP had been a massive success, no. 1 on the Billboard classical chart for two whole years, may also explain Barry Letts interest in having Simpson work out his score on a synthesizer. Carlos’s success changed everything for electronic music and inevitably the RWS

Back in (a) Covent Garden

As a coda to that sidetrack, in 1973 Simpson created an album of classical pieces using the synthesizer. This was a blend of traditional orchestra and synthesizer produced at Brian Hodgson’s new Electrophon Studio in London’s Covent Garden. Titled ‘In a Covent Garden’ – playing on the studio’s location and (I think…) the painting ‘In a Convent Garden’ by George Dunlop Leslie, which hangs in Studley House, Liverpool (

“This machine has the power to effect men’s minds. And it’s growing stronger

Finally, back in the ‘World of Dr Who’, an ever so slightly lighter version of the ‘The Keller Machine’ than that included on the ’21 Years’ RWS compilation (REC 354, 1979) (labelled as ‘Minds of Evil’, but let’s not start all that again). This terrifying cue is also from, (watch it) ‘The Mind of Evil’, and the ‘machine’ being the aforementioned, Clockwork Orange-inspired, mind control device. The growling bassline and strident melody are really effective here, rising to a dramatic climax before collapsing in a downwards ring-modulated swoop. That ‘sting’ echoes the one added to the closing titles. around this time.

As I said at the start, the intrepid use of EMS synthesizers to provide incidental music for the entirety of series 8 of DW was a milestone. The first time synthesizers had been used to soundtrack television drama, using the first commercially available synthesizers, and in prime-time. Sure, DW was a natural home for this vividly modern aural experiment, but it was still pretty amazing that this was finally possible – and on a BBC budget! Whilst ‘Switched on Bach’ had made a big splash, and the spin-offs were coming thick and fast by the time this show aired, the BBC had stolen a march on Hollywood (in the shape of Stanley Kubrick) and the singles chart wouldn’t begin to go

Barry Letts was no doubt pleased with the cost saving of having Dudley play his own compositions on the Workshop’s gear, and this continued into the start of series 9. But, as ever, nothing gets as old faster than a new sound (especially one so laborious) and gradually Simpson worked out a balance between the acoustic and the electronic, which he felt was more effective than either on its own.

Simpson and Hodgson’s work on Series 8 impressed EMS who included two pieces on their demonstration disc ‘Sounds from… EMS’ in 1972. But, it wasn’t easy. In fact “it nearly killed them”, according to Mark Ayres. The fact that you could play the synthesizer was one thing. Recording all the parts and getting them right was now complicated by having to set up each sound, track after track and take after take, one at a time. They couldn’t carry on like that forever.

Collector’s Corner

It’s hard to judge exactly how well any BBC Records release did for sales as data is not available to me. The singles chart was only expanded to a top 75 much later too, so lots of middling hits exact success is unclear. What seems to be the case for much of the BBC Records singles output is that a relatively small run (in the single-figure thousands perhaps) would be pressed and distributed to test the market. If the associated programme took off and, the records sold, more would be pressed. However, given that Moonbase 3 more or less flopped, and was soon forgotten, it would be amazing if the theme single had any sales impact at all. Even the appearance of the really quite popular at this stage, Doctor doesn’t seem to have lifted its fortunes much. That’s understandable given this isn’t the theme music and it takes a whole minute to get to a recognizable tune, which is then menacing and alien sounding. And remember this is before Doctor Who fandom, to whom it could have been marketed, had really got going. Simpson made it clear that this disc was a rarity when he donated it to the auction at Panopticon VII in 1986 too. Only 7 people on Discogs list this as in their collection, which is typical for these types of singles. The only copy available is £30 and it’s never sold for less than £15. I had to pay something similar to get a copy from eBay too. So, if you see it advertised as “rare” they are right, for once.

The Best Albums with The World of Doctor Who, Ever…

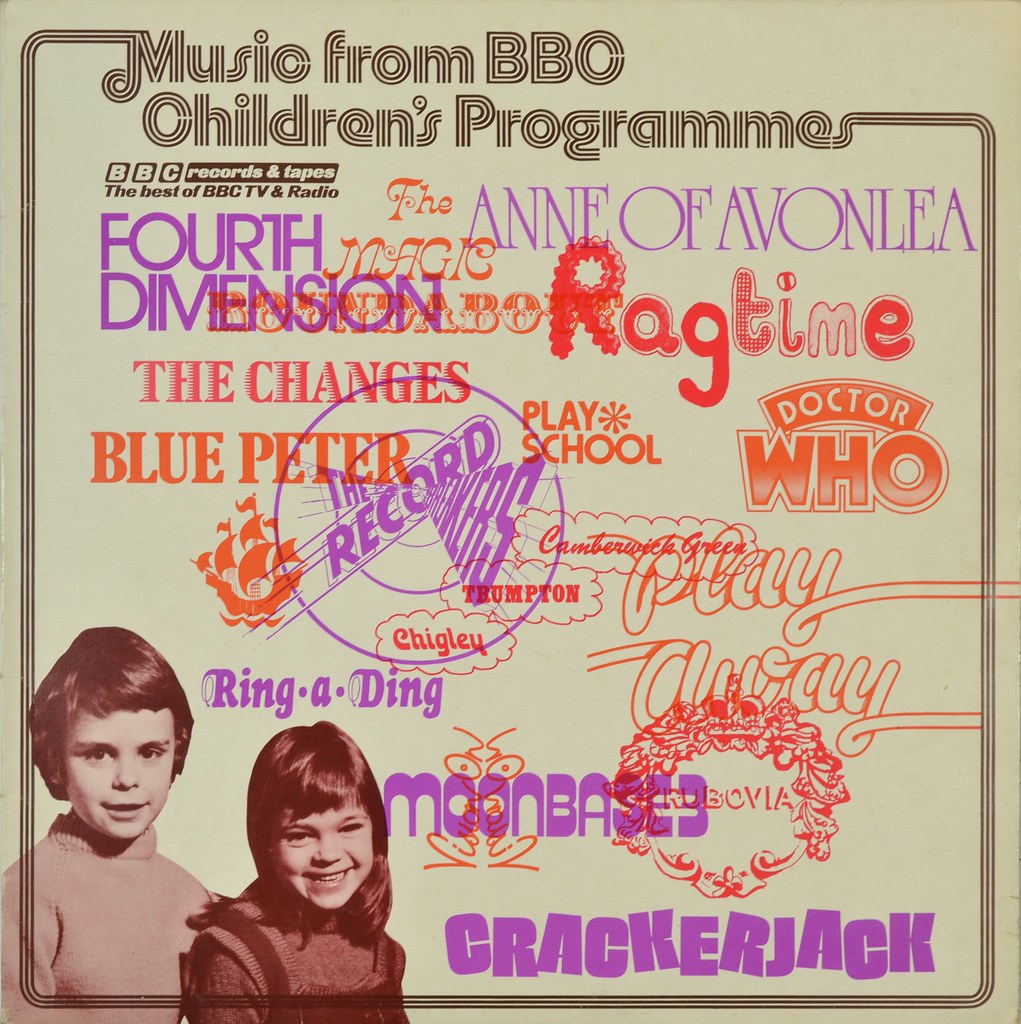

Y’know, for kids!

Both sides of RESL 13 turned up on ‘Music From BBC Children’s Programmes’ (REH 214) in 1975. The six episodes of Moonbase 3 were only broadcast once on BBC at a time when most children were already abed, and it wasn’t aimed at them anyway, so this appears to be a fairly lazy bit of re-licensing by BBC Records. It doesn’t sit alongside Playschool and Chigley that comfortably. If you want copies of these tracks though it’s a better deal than buying the single. And, just maybe, the label

World Within Worlds

‘The Worlds of Doctor Who’ CD released by Silva Screen in 1994 at least provides a clean digital version and is even better value for Doctor Who fans.

There are also a few of Dudley Simpson’s works from the seventies DW on this album. These are versions produced electronically by Heathcliffe Blair for a previous CD on Sila Screen, ‘Doctor Who – Pyramids Of Mars’. These got the full seal of approval from Simpson, but haven’t aged particularly well owing to the limitations of early nineties synthesizers. As Blair himself has reflected, they really deserve a full recreation with an orchestra. It’s worth noting that Blair was able to get the original scores from the BBC archives, which include all the detailed notes Simpson made regarding setting up the synthesizers at the RWS.

Moonbase 3 – Return to Base

Great TV Show

‘Moonbase 3’ made it onto the 1974 themes compilation ‘Original Music from Great BBC TV Shows’ (REB 188). By then it had not been recommissioned and no repeats were planned, so either BBC Records were short of cheap themes to put on this compilation or it was already recognised as a great theme. Probably both. Well, they’d already used two Paddy Kingsland numbers, two from HM Welsh Guards and two from The Early Music Consort Of London, all on a price code B (heading up to above £2 as stagflation started to take hold) record, so maybe they were keeping an eye on the costs.

Space Themes

‘Moonbase 3’ was paid another visit on ‘BBC Space Themes’ (REH 324) in 1978. I could say that this was another off-hand, cost-conscious gesture by the

Closing sting

That’s not the last we’ll be hearing from Dudley Simpson in Discographic Workshop. There’s a bit more Simpson to come yet! The last word here though, is his.

“Doctor Who was the greatest challenge of my life. Every episode presented a challenge. Every moment. They were funny days. But I miss them.” Dudley Simpson

Sources

- https://tardis.fandom.com/wiki/Doctor_Who_Wiki

- https://whitefiles.org/rwi/index.htm

- tardis.fandom.com/wiki/ List of incidental music composers

- 45 Cat – The Brothers

- rateyourmusic.com The World of Series, DECCA Records

- https://www.tapeleaders.co.uk/

- Special Sound – The Creation & Legacy of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop

- Analog Days The Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer – Trevor Pinch, Frank Trocco

- Sight & Sound interview with Kubrick, Spring 1972

- Doctor Who the 50th Anniversary Collection – Silva Screen

- Doctor Who: Adventures in Time, Space and Music – Episode 43 – Series 8, Part I – Dudley Simpson and Brian Hodgson Join Forces Against the Claws of Axos

- Time Signatures: Music and Sound Design in Doctor Who (1963–89, 1996, 2005–) by Emily Anne Kausalik

- Radio Free Skaro #612 – 120 BPM

- Nothing at the end of the Lane issue 4, Autumn 2015

- Doctor Who Magazine – Issue 521 – February 2018

- Doctor Who Magazine – Issue 524 – May 2018

- https://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/oct/20/peter-zinovieff-ringo-ems-synths-interview

- The Millenium Effect – Heathcliffe Blair CD

Thanks for this blog – fascinating material!

Can I suggest a correction for the paragraph on Peter

Zinovieff? The English composer with whom he

collaborated is Harrison, later Sir Harrison, Birtwistle (1934 – 2022), not Harrington.

Amongst other things, Zinovieff realised Birtwistle’s tape piece Chronometer at EMS, and also wrote the

extraordinary libretto for his opera The Mask of Orpheus, premiered at English National Opera in 1986.

Thank you for the kind words.

And also thanks for pointing out the error there. Harrison, indeed, Birtwistle. So silly of me!