Contents

Doctor Who

We (ahem) materialise into the third part (and half-way point) of a thorough review of all the BBC Records (& Tapes) releases featuring the Radiophonic Workshop. Previous parts have taken an in-depth look at the compilation albums and the solo LPs. This part is all about the Workshop’s many dealings with The Doctor and this post is dedicated the first such release.

Doctor Who (hereafter, DW) began on BBC TV in 1963, and with a little help from the Daleks, was a ratings smash-hit, reaching viewing figures of 12 million. The show continued to be hugely popular right through to the eighties, when it finally lost its footing and was cancelled after series number 26, in 1989. Of course, it was resurrected in 2005 and continues to this day, as exciting and popular as ever, but here we’re going to look back to the golden age of the original series.

The BBC Radiophonic Workshop were part of DW production from the very start and did much to contribute to the success of the show in its early days. Initially, theme music and sound effects, then later the incidental music was augmented at the Workshop and finally, for a period, all the show’s music was coming from their Maida Vale studios. Any Radiophonic music was extremely time-consuming to produce in 1963 however, and until the advent of relatively cheap and playable keyboard synthesizers, along with high-quality multi-track recorders, it simply wasn’t practical from the Workshop to soundtrack hours and hours of television every year.

BBC Records were eventually able to exploit the theme music, sound effects, the incidental music and, in those painful years for fans before VHS tapes, a whole story adapted for audio. DW was quite the money spinner for BBC Enterprises during the period of BBC Records’ operation. Through licensing all kinds of merchandise, as well as their own discs, the cash was rolling in. In ‘Space Helmet for a Cow: The Mad, True Story of Doctor Who (1963-1989)’ Paul Kirkly relates how, in the mid-eighties, Douglas Adams – both a former Doctor Who script editor and someone who tried and failed to give BBC Enterprises a slice of his own, highly lucrative, creative output – wrote to the BBC pointing out that Doctor Who earned them seven times what it cost to make. The BBC’s reply: “Our accountants don’t total income that way.” Adams, in reply: “You should fire your accountants and make more Doctor Who”. Which just goes to show, that the BBC’s commercial arm was really not involved in sustaining the programmes that were its lifeblood. A deeply unsatisfying situation in many ways and a quirk of public service broadcasting which remains controversial to this day.

So, resisting the temptation to make some allusion to joining me on adventures in space and time, join me as we, err, dive into a time vortex and land on the mysterious world of the BBC in 1963.

Signature Sound

The original, Radiophonic Workshop version, of the Doctor Who theme, realised by Delia Derbyshire with technical assistance from Dick Mills, is simply put, the greatest theme music ever created for a television programme. No, Rolling Stone Magazine, it isn’t ‘Where Everybody Knows Your Name’ from Cheers. That’s just a nice song. The DW theme – a signature tune, in the BBC’s parlance – was not only written and realised specifically for the programme, it’s still in use after more than fifty years. It is also not only a great musical score, it’s an outstanding production and an anthem for British science fiction; the Radiophonic Workshop; British electronic music, and the BBC. It is important.

The Dawn of a Realisation

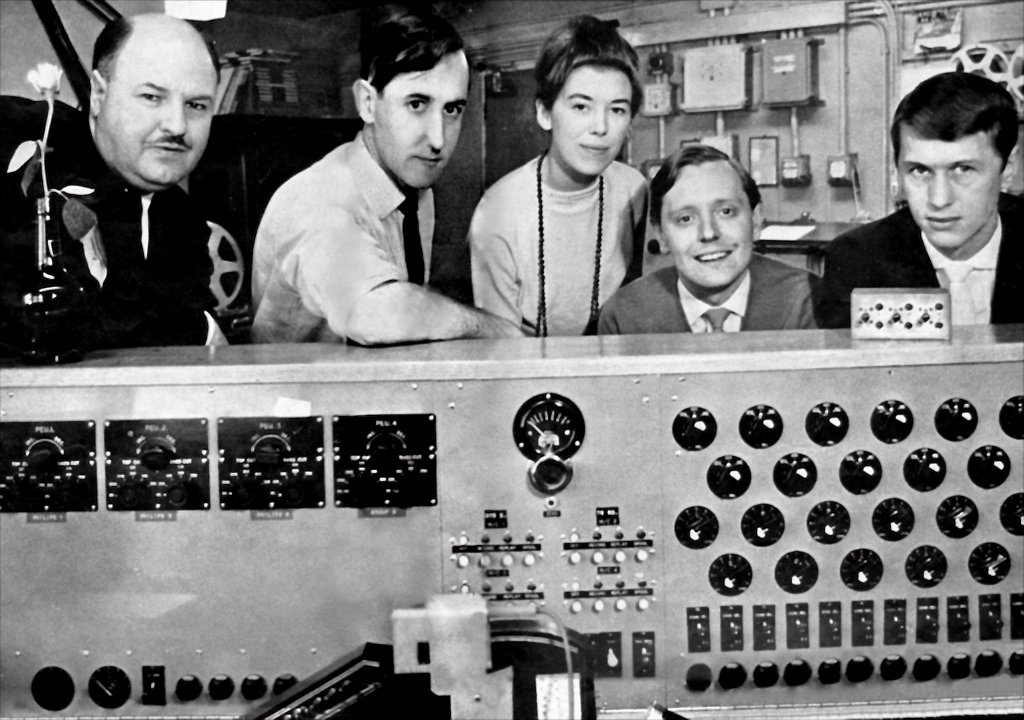

Cary to join us?

The theme music to the new children’s sci-fi serial on BBC television was originally going to be commissioned from a giant of the early British electronic music scene, Tristram Cary. Cary’s story weaves in and out of the Workshop’s own and it’s somehow fitting that he should have a walk-on part in the prologue to its most important and famous work. A change of producer during the development of DW ended Cary’s involvement in the signature tune, but he would still play a role in the first series, providing the incidental music to its most popular story ‘The Daleks’. An interesting question is: what would his theme have been like? As we saw previously with Elizabeth Parker’s experiences as his student, Carey was later known for his technical mastery and a rather formal approach to electronic music, rather than strong melody and stirring tea-time adventure series anthems. I think we can conclude that it wouldn’t have been anything like what we ended up with but beyond that, there is simply no answer. Arguably, it’s less likely to have been as much of a success as the final piece, but it would no doubt have been fascinating and just as ground-breaking.

Avant Garde a chance

When Verity Lambert took over as producer of DW she was keen to get a theme tune from experimental French group Lasry-Baschet Les Structures Sonores. This choice was eminently sensible, as they were the darlings of the avant-garde and their other-worldly music was ideal for the show. In the event, they were too busy and would likely have been too expensive for Lambert’s budget. However, their influence can be detected in the theme that we ended up with, even if that may not have been completely intentional. There’s some irony to this. The core instrumentation of the group were structures created by the brothers Francois and Bernard Baschet. These were purely acoustic instruments which used metal, glass and plastic as resonators. Their ethos was to advance acoustic musical instruments in the twentieth century which is was somewhat of a contrast to the prevailing use of electronic means to explore the outer limits of music at the time. In fact, they set themselves up somewhat in opposition to electronic music of the time, with its preference for the abstract. This difference wasn’t only a matter of technique. Cary and his ilk had a fundamentally different view of what the Modern and experimental music should be and sound like. No wonder then that Lambert looked to these experimenters in preference to Cary.

Doctor in-house

With the more high-brow electronic music unsuitable for the signature tune to a children’s show and the more palatable Gallic experimenters out of reach, something which could marry the two ideas was required. Something in-house at the BBC, ideally. Lambert was directed to the Radiophonic Workshop and was welcomed with open arms. You may wonder why the Workshop weren’t the first and obvious choice for Lambert and her predecessor, but at this time they were not a musical department. Sound effects were their stock in trade, of course, but they did not employ composers. John Baker had joined in 1963 and Delia Derbyshire the year before but it wasn’t as if they had immediately started producing swathes of music, especially for TV. The Workshop’s Organiser, Desmond Briscoe had carefully guided the new department from its inception and whereas the other originator, Daphne Oram, had to leave to pursue her passion for electronic music, Briscoe played a long game within the BBC. According to Derbyshire, when she joined Briscoe (had already, or somehow as a result of her joining) changed his mind about what it was possible to do with electronic music. By the time Doctor Who came up, they were ready to plant their flag in primetime TV, and what a great opportunity! Derbyshire had recently been on a fact-finding mission around European electronic music studios and when Lambert came knocking she had only produced one piece for television, ‘Time on Our Hands (see ‘BBC Radiophonic Workshop – 21’ REC 354). A quick listen to this piece shows how the DW realisation evolved from her earlier work. Writing a memorable theme was not an easy matter though. With Lambert asking for something to draw viewers in as well as being cutting edge and suitably fantastical, a collaboration was proposed.

Going with the Grainer

Accounts vary, but it was probably Briscoe suggested that they ask Ron Grainer to provide the score for Doctor Who. Grainer was the go-to man for themes at the time, so there couldn’t have been a better person to ask and Lambert would have had a lot of confidence in this choice. As luck would have it, in the recent past the in-demand composer had just worked with the Workshop on ‘The Giants of Steam’ television series. For this score the Workshop had created rhythm tracks which sounded like steam trains – prefiguring Kraftwerk’s ‘Metal Auf Metal’ from their ‘Trans Europe Express’ album by fifteen years – and then a jazz orchestra played over the top. This was not a new idea by the way. The Ealing Studios classic ‘The Man in the White Suit’ covered similar territory back in 1951. I’ll talk more about that in a later part of the review. According to Lambert, Grainer was extremely enthusiastic about the possibilities of electronic music and was only too happy to contribute. On the other hand, he was tiring of the intense collaboration TV scores entailed, but as he’d enjoyed working with Workshop he agreed to provide a score for DW, and leave them to produce it. It appears that assumed they would follow the same approach they’d taken with Giants of Steam – create some suitably spacey sounding electronics as a backing track and then they would book a band to beef up the tune. Little did he realise that their ambitions went much further than that. After viewing a film of the titles sequence alongside Derbyshire, he handed her his single sheet score for the DW signature tune and went to his house in Portugal for a well-earned rest.

“Inch by Inch by Inch”

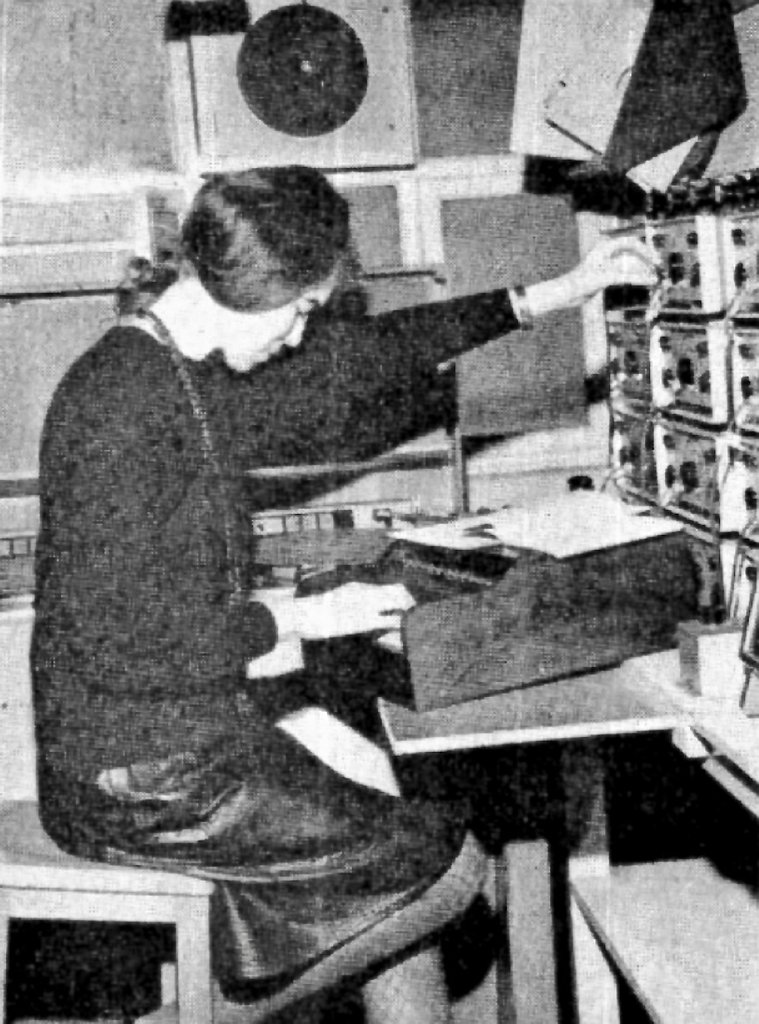

Presumably, with no intention of involving a band of musicians, Delia Derbyshire then set about realising Grainer’s score with the tools she had to hand. Using acoustic and electronic sources recorded to tape and then cut and spliced together Derbyshire, assisted by Dick Mills, hybridised the swagger of Grainer’s tune with the ‘space music’ of the French avant-garde, adding her own twists. This process, as Derbyshire has said “inch by inch by inch” was revolutionary for a mainstream television signature tune. No two notes were ever played together. Every sound was on a snippet of tape and the score was arranged by sticking the pieces together. Only when the assembled strip of tapes was played would it be heard for the first time. In all, three such tapes were created and they were played together, in synchronisation, to create the finished piece.

Bass

The bassline, which introduced the original version of the theme, was, according to Derbyshire, annotated by Grainer as a bass guitar and possibly bass bassoon. Derbyshire and Mills recorded the sound of a plucked string to use as the source material and underpinned it with a short, upwards swoop created with a square-wave oscillator – “nerp”. This additional grace note gave the bass notes a rich and undefinable depth that was neither acoustic nor completely electronic. The exposed bassline at the start of the arrangement could be compared with the twang of the prominent electric bass guitar in the James Bond theme. Dr No was released in 1962 and Daphne Oram has contributed some (uncredited) electronic sounds. The slight imperfection of splicing the tape by eye and by hand makes it seem both artificially regular and humanly played at the same time.

Melody

My feeling has always been, that for the melody Derbyshire was reaching for a sound somewhat like the Cristal Baschet, which was created by the brothers François and Bernard Baschet, or a glass harmonica. Knowing her propensity for analysing sounds into their component parts and building them back up again from single tones this one would make sense. Yet that’s not the whole story. It’s noted in deconstructions of the original theme’s component parts that Derbyshire uses an overtone on the melody. This addition creates a sound similar to the glass harmonica. Interviewed for Record Collector Magazine in 1997, Derbyshire explained that this is indeed what gives it that glassy tone. Surprisingly though, she goes on to say that the addition was a matter of necessity, not design. A sine-wave, which was used for the root of the melody, becomes all but inaudible as the notes descend down an octave. As the sine has only a single harmonic component the richer square-wave, added an octave higher, simply keeps the note audible. Derbyshire laments the lack of a saw-tooth wave as this would have provided much richer source material for her to filter to her desired tone. In this interview, she goes as far as to say that she would have liked to re-do the whole thing, which begs the question: what was Delia Derbyshire really imagining for the theme, if not the ethereal glassy tones a la Les Structures Sonores? Possibly, there was something in Ron Grainer’s annotations that she wanted to realise, but in the Masters of Sound documentary, she says that the swoops in his score were assumed by her to be sine-waves. Unfortunately, the original sheet has never been seen in public and as it seems lost, so we don’t know what that note might have been now. The result is still shocking and beautiful today. That the swooping melody was created only with a test oscillator and tape recording, one note at a time, with no live playing at all, save the turning of a dial to swoop the pitch, is all the more astounding.

Noise

The one element that Ron Grainer definitely needed the Radiophonic Workshop to realise in place of acoustic instruments was apparently described in his notes as “clouds” and “wind bubble”. These ideas appear to have been inspired by the graphics in the titles and again it’s very unclear how much Grainer scored and exactly what was left to Derbyshire. She and the whole Workshop knew all about wind sound effects. In ‘Masters of Sound’ she casually says “clouds, obviously, one thinks of, as filtered white noise”. Perhaps not obvious to everyone! It’s more than just some sound effects to build atmosphere though because the noise is a rhythm track. The filter has been used to create different tones, which hiss and suck in a counter-rhythm to the bassline.

“Did I write that?”

The completed arrangement was mixed together with careful use of reverb and that was that. It is minimal, adding to the sense of space, and later versions meddled with this, much to Delia’s chagrin. Ron Grainer was moved to ask “did I really write that?” to which the reply (depending on who you ask) was either “nearly” or “most of it”. Either way, he was delighted, dismissed any idea of having a band play along with it and moved to have Delia collect on half of the publishing rights. The BBC were having none of it though.

Later generations were left to wonder how to update this masterpiece. The TARDIS interior is regularly completely re-designed, but the exterior police box has gone through but few alterations down the years. Like the TARDIS, whilst it’s possible to change appearance in theory, in practice the theme is simply too iconic to be replaced. The show’s signature tune is still, to this day, Ron Grainer’s score, although the Workshop’s contribution has been barely detectable in recent times, although that looks set to change with the new version by Segun Akinola. Nevertheless, the original will always remain the most famous Radiophonic Workshop theme and a cornerstone of one of the BBCs most successful ever shows.

As Davd Cain points out in ‘Alchemists of Sound’, the best work of this kind is created when something wonderful is made despite the tools. He had been asked about a Golden Age of the Workshop and it can be said that the Doctor Who theme realisation meets that criteria.

Or, to put another way, as Mark Ayres says: “Ron wrote it and Delia made it magic”.

Variations on a theme tune

In 1963 there was no BBC record label, hence they were slow to fully capitalise on Doctor Who and Dalek-mania. In common with other BBC recordings licensed to outside labels, the first release of the DW theme music was put out on Decca records in February 1964. Over time, BBC Enterprises started to cash in on the show’s popularity and the Radiophonic Workshop, whose records were already doing solid business, were a significant part of that.

The Decca Decade

The Decca release is the first version of the DW theme created, and therefore we can assume the one Delia was most happy with. It wasn’t used on the TV programme though. For the next ten years, Decca had this version in the shops, so any changes made after this heard on TV were not released. In case you’re not familiar with it, the B-side to this Decca single has almost nothing to do with Doctor Who, let alone Radiophonic music, so we’ll move swiftly on.

Pilot error

After the titles were finished and the producers had had their say, other versions were created and used on screen. One of these is what you can hear on the ‘21 Years’ album. That was a curious choice as it’s a rather bad edit and it was only used (accidentally, we assume) on the never broadcast pilot episode.

Fit for broadcast

The bad edit was then replaced with another, better, version before the programme was readied for air. This broadcast version was eventually released on CD by the BBC as part of ‘Doctor Who at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop – Volume 1: The Early Years’.

Do you remember spangles?

As the years passed by, more tweaks and adornments were added to the theme as the show’s producers strove to keep things fresh. Derbyshire’s feelings about these adornments were not positive, using the epithet ‘tarting up’, but she understood the need to renew.

In 1966 Derbyshire reworked the theme to accompany the new titles for the second incarnation of the Doctor, played by Patrick Troughton. This involved adding an element which, is known by fans as ‘spangles’. The spangles reflected the new video feedback effects and their ascending glissandos were quite long-lived, being retained until the original arrangement was eventually retired. This version was never released by BBC Records, but, I have to say, I’m quite fond of the spangles, despite Derbyshire’s preference for not gilding the lily (sorry Delia!). This version, entitled ‘Signature Tune – A New Beginning’ was eventually released on ‘Doctor Who: 30 Years at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’, a 1993 CD issued by BBC Enterprises as part of a 30th-anniversary celebrations of the show.

Delaware, did they go wrong?

With a landmark tenth series on the horizon, the Workshop were asked to create an exciting new version of the signature tune. Naturally, the vast and expensive Synthi 100 ‘Delaware’ synthesizer was the obvious place to start. Brian Hodgson has owned up to this idea. With Derbyshire in a producer’s role, no doubt with misgivings from the start, Paddy Kingsland set to work. Although she wasn’t completely anti-synthesizers, the fiddly and recalcitrant monster from EMS wasn’t exactly a dream to work with, so it’s no surprise that Derbyshire left her newer, younger colleague to wrestle with it. The results were unpopular with almost everyone and although series producer Barry Letts was keen enough he was over-ruled. Two early edits had already been shipped off to Australia though, so it did get some air time there, at least.

After that embarrassment, there would be no radical reworking of the theme for quite some time and Letts kept the titles the same from 1974 until his successor took over.

The Derbyshire Variations

- First master August 1963 – First single release, Decca Records

- Bad edit – ‘21 Years’ LP, BBC Records

- Good edit – Broadcast only and then BBC CD

- Spangles – Broadcast only and then CD

- Delaware – Produced by Derbyshire and realised by Paddy Kingsland. Broadcast briefly and then CD

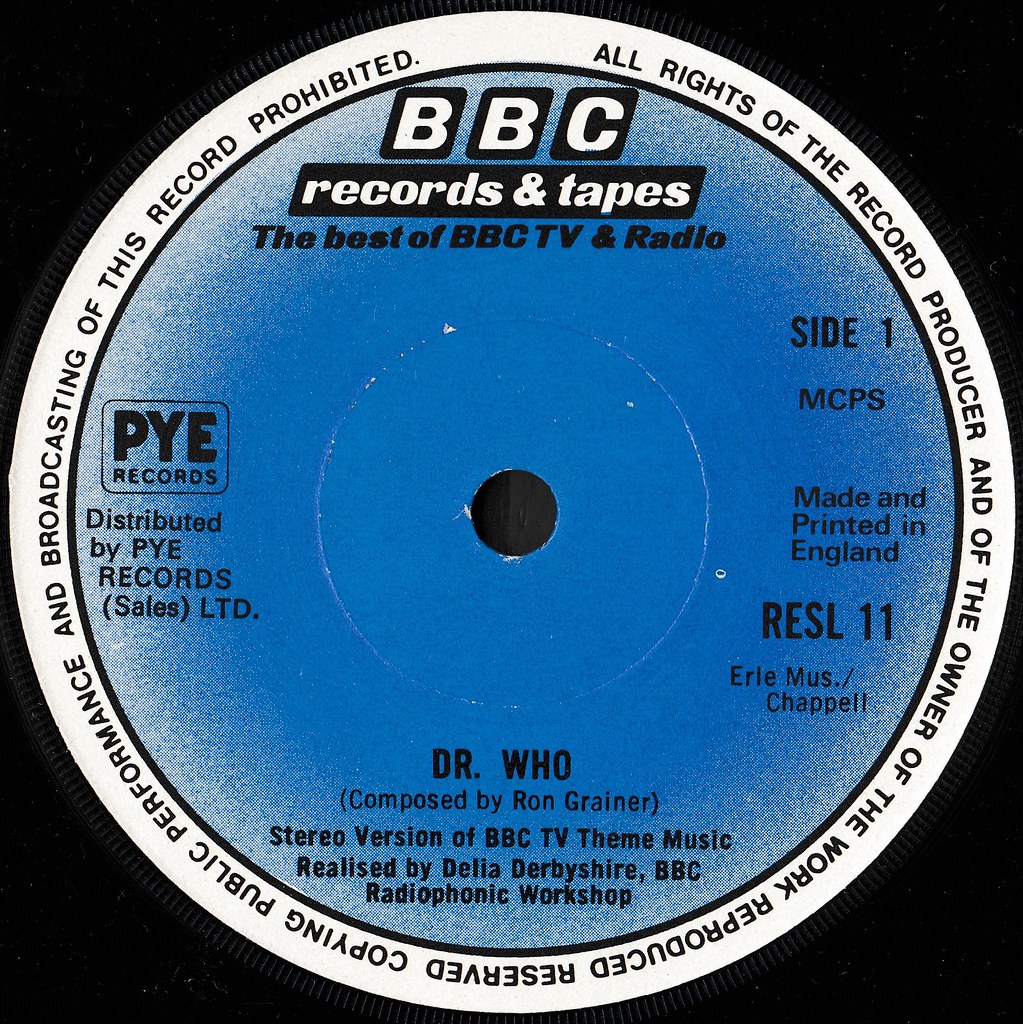

- Stereo – Single version (See below)

Doctor Who / Reg

Decca licenced the original Doctor Who signature tune for five years, starting in February 1964, and re-pressed it several times in that period. Even though by early 1967 BBC Radio Enterprises was up and running with a record label, and the first Workshop album had been released in 1968, they didn’t begin issuing singles until September 1970. It seems that Decca got an extension to their licence and reissued the record eight years later, in February 1972, with the ‘box logo’ labels. That license appears to have either been on a rolling one-year extension or had a flat three years added on.

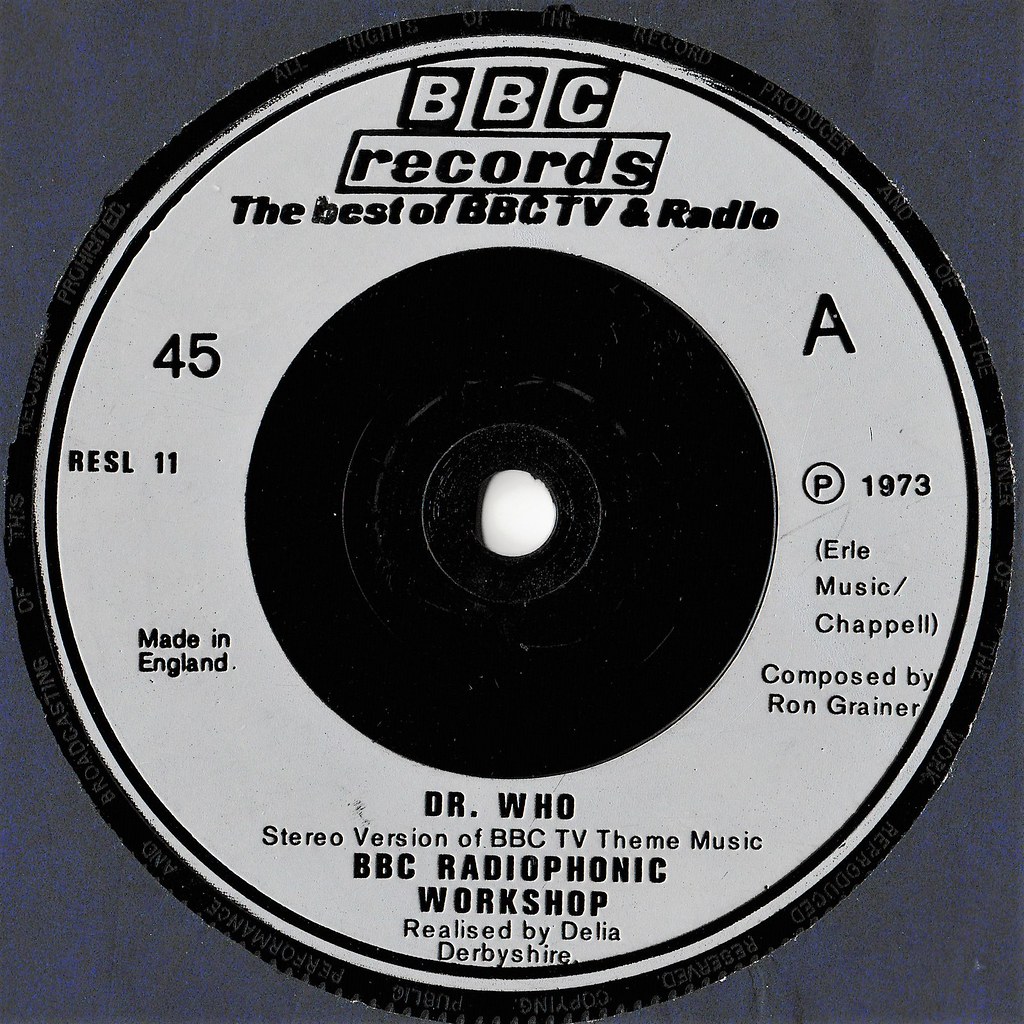

In either case, the BBC Records label finally got in on the act with a new stereo version of the theme released in May 1973, during DW’s tenth series. In those days a series was twenty-six episodes (imagine that happening now!) and this one had started on 30th December, so the timing of the release was not exactly ideal. Maybe they were waiting for the Decca license to run out or perhaps there was a bit of a last minute change to deal with.

As the Delaware version had been quietly rejected, the only option for the BBC Records single was to revisit the original. Broadcast television with stereo sound wasn’t launched in the UK until 1991, so it was created purely for BBC Records because they needed a new version to differentiate their release from Decca’s. Also, they had been probably been expecting the spectacular new synthesized version to be available, but as that hadn’t worked out they would have put a worried call into Desmond Briscoe’s office to find out what could be done instead.

Created in 1972 by Derbyshire, again with assistance from Paddy Kingsland, it had the cliff-hanger sting that now introduced the show’s end titles and Brian Hodgson’s TARDIS sound effects over-dubbed, for extra excitement.

There were no spangles on this version, which must have confused and even disappointed a few fans who might have expected what they heard played over the show’s titles to be on the record put out by the BBC! One must assume that Derbyshire vetoed their inclusion and kept things as close to her original as possible. They would have sounded nice in stereo though.

This release would credit Derbyshire’s realisation’ for the first time and it was shortly after this version was completed that she left the Workshop. It is some comfort to think that she was able to get this (mostly) respectful version of her magnum opus released by the BBC, with due recognition, as one of her last acts there. On the other hand, the issues with the Delaware version and only being able to get a souped-up version of her ten years old version released, probably contributed to both being unable to come to terms with the changing expectations and feelings of stagnation. It should be said that, when interviewed much later, Delia professed herself unsure why she left.

B Reg

Instead of putting another Delia Derbyshire composition on the B-side (or the scorned Delaware effort) they opted for the jaunty ‘Reg’, the signature tune from the BBC’s Africa Service. Derbyshire may not have been around to protest about the choice for the reverse of the single, but more likely she would have been happy for Kingsland to get some of the limelight given that his hard work on the Delaware version had been junked. Another, more prosaic, explanation was that ‘Reg’ was mixed in stereo. Paddy Kingsland’s solo LP Fourth Dimension, released later the same year, was somewhat of a stereo showcase and as ‘Reg’ was included on that album it is perhaps clearer that the intentions for this single were as much about stereo as anything else. Presumably, the original mono version of the DW theme was ruled out as a b-side for this reason – and there was nothing else in the Doctor Who archive that was in stereo. One final note on ‘Reg’: Fourth Dimension was originally supposed to be a split album between Kingsland and John Baker. Baker’s half didn’t arrive and there was a need for more tracks from Kingsland to fill it up. As ‘Reg’ was already promoting Paddy’s talents on the DW single it makes a lot of commercial sense to include it on his album.

BBC Records were not really in a position to advertise their wares on ITV, but they, of course, took advantage of their exclusive right to publicise their releases on BBC television. Once such notice (and I do mean notice, because no-one in adverting would class it as an advertisement) came at the end of the sixth and final episode of DW story ‘Planet of the Daleks’. After the BBC continuity announcer has reassured us that the Doctor will be returning soon, albeit for a Green Death, a photo of a tatty copy of RESL 11 appears (edge wear along bottom of front sleeve, VG+) and we’re told that it will be in “most” record shops soon. This was Saturday 12th May and the record was released on the following Friday.

Sleeves and Labels

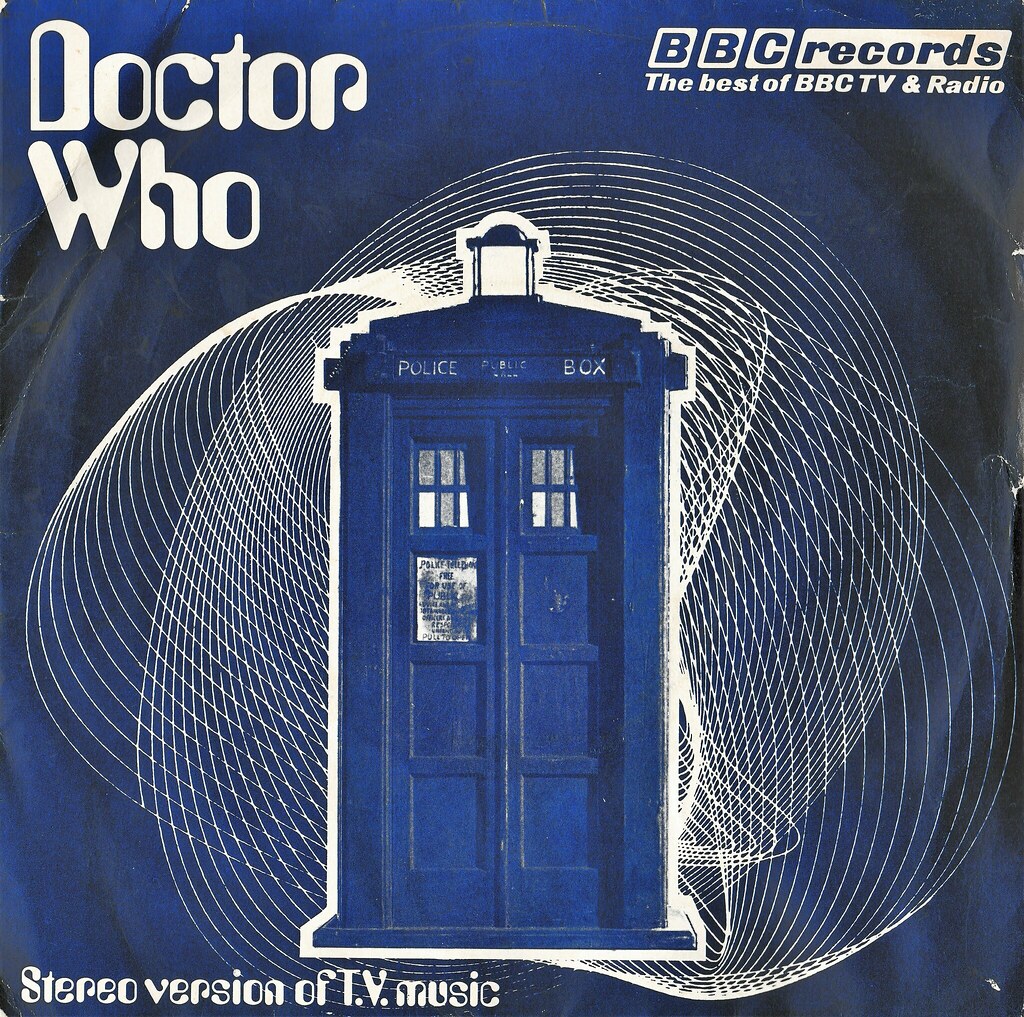

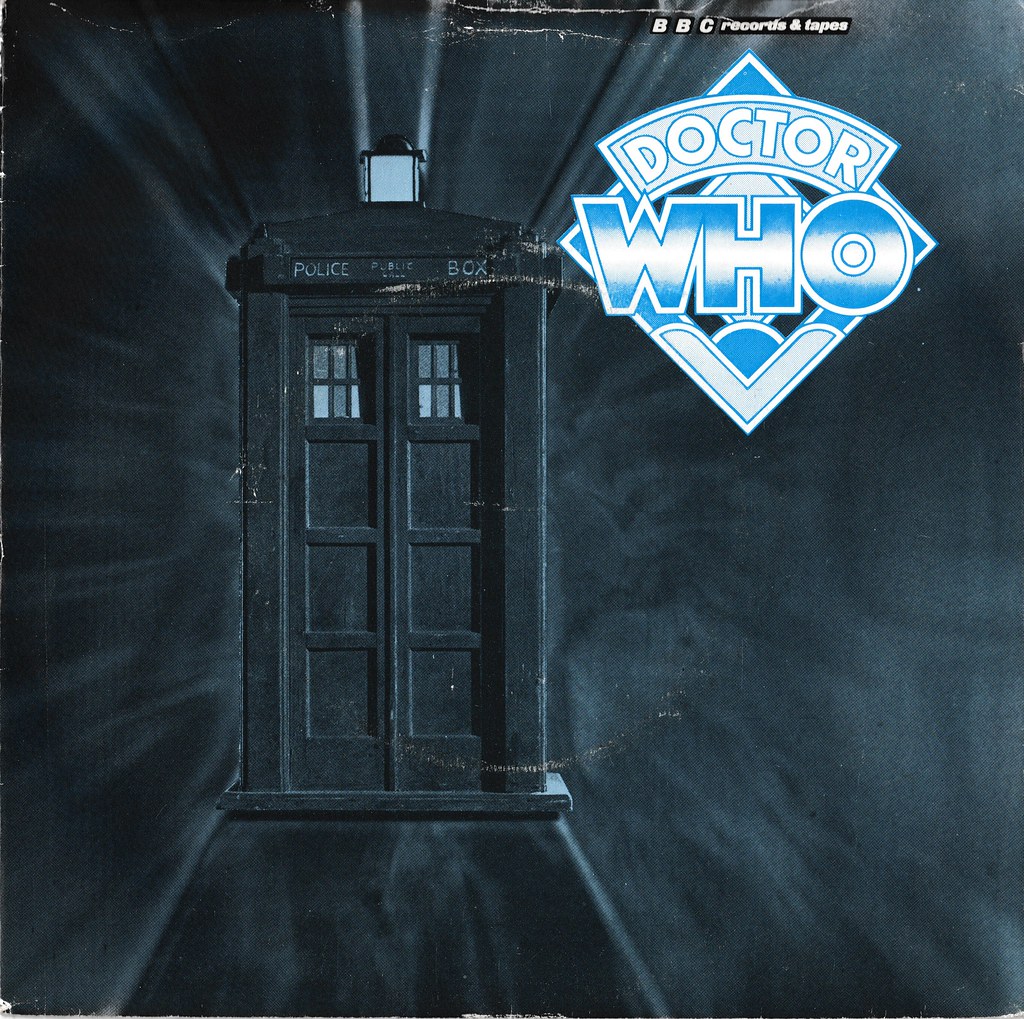

RESL 11 – Issue 1

The first issue’s design is a harmonious meeting of Doctor Who and BBC Records iconography by Andrew Prewett. The placing of the TARDIS against the background of the BBC Records’ harmonograph emblem works perfectly, being redolent of the time vortex.

The TARDIS takes centre stage in the artwork, but it seems to have landed in a previous BBC Records release – Victorian Poetry (RESR 21), also designed by Andrew Prewett. Something to do with The Child of Time, eh fans? It’s just been rotated and flipped over, but it’s the same harmonograph.

The typeface used on the sleeve is Amelia by Stan Davis and in a break from usual protocols the back cover uses this font too.

Amelia was used in the design for ‘Yellow Submarine’ by The Beatles in 1969, masses of sci-fi novels, synthesizer albums and all manner of early seventies wackiness. It perhaps wasn’t chosen by designer Andrew Prewett entirely without reference to Doctor Who though.

In ‘Planet of the Daleks’ episode 1, broadcast 7th April, 1973, the TARDIS’ monitor helpfully explains that…

Putting aside some serious questions about the design of the TARDIS’ life-support systems, you will notice that the font chosen for this important message is Amelia. Co-incidence? Perhaps, but it seems just as likely that Prewett was creating the sleeve for RESL 11 around the same time that this episode was on-air and took a bit of inspiration. Either that or his design was already complete, proof copies were at the production office late in 1972 and they decided to have some fun with it. Either way, it was a nice bit of subtle cross-promotion.

UPDATE: Viewing the story broadcast before Planet of the Daleks after writing this, Frontier in Space, it became apparent that Amelia was in wide use on the show earlier than in the few weeks before the release of RESL 11.

This first issue is one of only a handful of singles that were given the blue/white logo label design used for hundreds of BBC Records LPs throughout the seventies and into the eighties.

Note that Delia Derbyshire is given full credit here. That means she was at last being paid royalties from the sale of these records. EDIT (As corrected by Mark Ayres) “With respect – and I know people find this difficult to understand – Delia did nothing on the recording that earned the right to a royalty. She did not compose the music, she arranged and realised it. And she did that as a BBC employee, on a good salary and benefits, so the BBC owned the rights in her work. That’s how it always works“. Thanks Mark!

RESL 11 – First issue, die-cut sleeve

Picture sleeves were not on offer for long and most copies would have been found in shops with a plan die-cut paper cover. As evidence of the constant repressing of this single you can marvel at exactly how many different label variants are out there over at 45Cat.

RESL 11 Issue 2

The blue/white paper labels were soon replaced as the oil crisis pushed the price of vinyl up and record labels looked for ways to cut costs. One way to get cheaper vinyl was to replace the glue and paper with a moulded label pressed in along with the grooves. Furthermore, these moulded label releases – sometimes referred to a ‘plasticrap’ – were issued with plain blue cut-out sleeves.

RESL 11 – Issue 3

The third issue of RESL 11 was released in 1976. By now the oil crisis was over, BBC Records had rebranded with the ‘and Tapes’ suffix and they’d arranged a distribution deal with PYE Records. Paper labels were back, although the smart LP style design was replaced with rather dull airbrushed(?) blue splodge. There was also another short-lived picture sleeve, still in monochrome but with a photo print and silky finish paper. DW’s ratings were riding high at this time, so there was no need to skimp.

The diamond branding logo was now firmly in use, after missing out on the original issue too. The Tardis is back, but now the time vortex is a still image from the opening titles, introduced in 1974 and created with slit-scan camera techniques.

You will note that the Tardis has been spruced up by the BBC Records art department, compared to the rather shoddy looking effort in the titles (what is going on with that light?). Sadly the colour has been lost from the original but this may have been an aesthetic choice and is hardly missed.

Dematerialisation

The original theme couldn’t last forever. It would regenerate of course, but Delia Derbyshire’s realisation went as far as it could and then had to make way for something more of the times. We’ll take a look at what that was in a later part. The original would be back on BBC Records though and we’ll be taking look at those appearances too. Its lasting legacy though is the joy and fear and excitement and wonder it brought to viewers.

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Doctor_Who

- http://www.effectrode.com/making-of-the-doctor-who-theme-music/

- http://wikidelia.net/wiki/Doctor_Who

- https://www.dwtheme.com

- http://www.effectrode.com/making-of-the-doctor-who-theme-music/

- http://left-and-to-the-back.blogspot.co.uk/2012/07/brenda-and-johnny-this-cant-be-love.html

- http://www.shannonsullivan.com/drwho/serials/ppp.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amelia_(typeface)

- http://www.artofthetitle.com/feature/doctor-who-50-years-of-main-title-design/

- http://tardis.wikia.com/wiki/Title_sequence

- http://timworthington.blogspot.co.uk/2017/02/sweeps-swoops-cloud-windbubble-and.html

- https://www.mfiles.co.uk/doctor-who-music.htm