Welcome to the third and final post in Part 2 of Discographic Workshop, which is dedicated to the solo albums of the Radiophonic Workshop. And, for want of a better place to put it, there’s also our first single.

Contents

- Through A Glass Darkly

- The Astronauts b/w Magenta Court

- The case of the ancient The Astronauts tapes

- The Living Planet – A Portrait of The Earth

- Sources

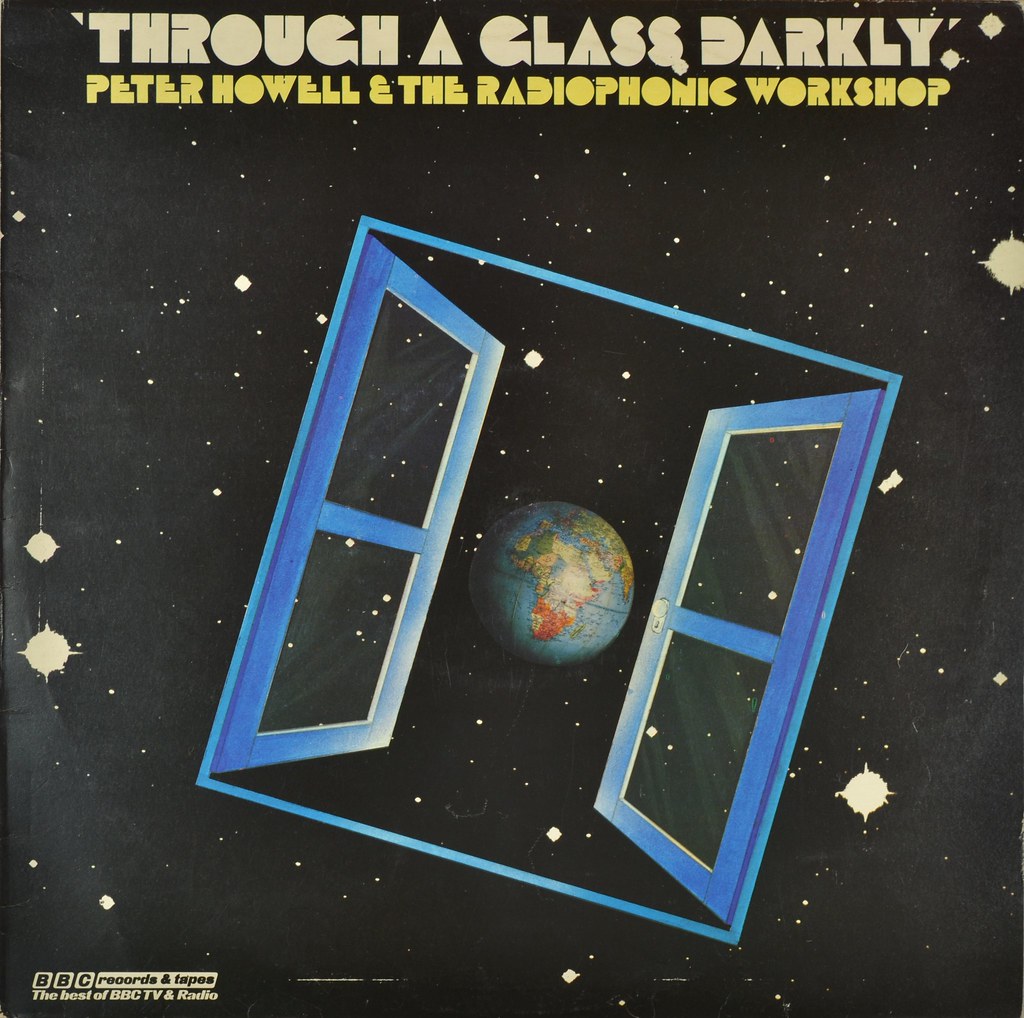

Through A Glass Darkly

“When you’re working from scratch there’s nothing’s worse than having the whole universe to choose from.” Peter Howell

Peter Howell may have some misgivings about the blank canvas* offered by electronic music, but when he needed engage in a spot of self-promotion at the Workshop this was the challenge he took upon himself. In contrast to all the other Radiophonic releases reviewed here so far and to all of the other Radiophonic Workshop material released by BBC Records, this record was the composer’s own idea.

*Or, rather, tape. Although that wasn’t always the case and as we’ll see in a later part, re-using tape sometimes brought its own serendipitous opportunities.

How Well Do You Know Peter?

Peter Howell was born in 1948 grew up around Brighton. As a fan of The Shadows he came to love the guitar and as the sixties started to swing he took that forward into an interest in the folky picking of Bert Jansch and Pentangle. He was supposed to follow his father into a career in law, but as we know that was not his true calling.

By the late sixties Howell was playing and recording music with local bands. There was something in the air at that time which can be loosely and lazily lumped together as a kind of anti-Modern backlash. People were losing faith in the technological revolution which had propelled us through the Second World War and out the other side and there was a concomitant rejection of city living in favour of the country. If you were already in the countryside you might have been surprised to find that you were suddenly hip, after decades of being told the city was where everything interesting was happening. A more prosaic explanation for this embracing of all things pastoral is simply that artistic ideas about the Modern had been done.

Peter Howell was actually in the right place already, but what’s more intriguing is that he combined pastoral folk music with a psychedelic application of tape manipulation techniques. As we’ve seen already, Pink Floyd had been to visit the Radiophonic Workshop, and for pop music in general there were all sorts of interesting mixing of ideas in London, New York, San Francisco and across Germany in the late sixties which led to much of the more interesting sounds of the seventies. There was also a vital electronic music scene in all of those places, which is not coincidental.

H&F

Pete’s Howell’s early musical career was a collaboration with childhood friend John Ferdinando. Between them, they self-published five albums in very small numbers.

- Peter Howell and John Ferdinando – Alice Through The Looking Glass (1969)

- Tomorrow Come Someday – Tomorrow Come Someday (1969)

- Agincourt – Fly Away (1970)

- Ithaca – A Game For All Who Know (1973)

- Friends – Fragile (1974) Not pressed due to starting at the BBC

This project was part-time, DIY and more representative of most people’s experiences of producing popular music than those of rock gods. It was small scale and local. They had a go and nothing really took off at the time. Howell wryly attributes some of this lack of success to spending too much time in coffee shops thinking up band names! Since being apparently lost to obscurity the albums have all been rediscovered and reissued. The same retromania that give rise to this blog has ensured that no stone is left unturned in late 60s British pastoral psychedelia. As it happens, the quality of Howell and Ferdinando’s work was well worth another shot at fame, albeit still within fairly modest circles of interest.

Through A Looking Glass – Proscenium Archly

The duo, were given initial impetus to make records by a commission to create a soundtrack to a theatre production of Alice through the Looking Glass in the rural idyll of Ditchling, in the Sussex downs. This was local amateur production which would have been unremarkable outside of Ditchling but for the a few notable features, not least the music. The role of Alice was taken by a very young Martha Kearney, better known now as a BBC news presenter. The set and costume and design were excellent and with the pre-recorded and uncanny soundtrack it was a great success, still talked about in Ditchling.

It’s again interesting, the contribution of drama to the roots of Radiophony. The connection came through Ferdinando’s family who had lived in or near Ditchling and had “theatrical streak running through it”. Ferdinando had been working backstage at the theatre since 1966.

The album came about as a souvenir for cast and audience members rather than as a serious attempt at a release. Only fifty were pressed – they were surprised by its popularity, but it gave them confidence to carry on. The resulting record is a mix of folky guitar, organ and found sounds interspersed with (pretty rough) recordings of the staging of Alice. There are some interesting tape effects too – Howell had a Revox 736 which allowed for a rudimentary form of multitrack recording.

That brief summary is an under-estimation of the album’s importance, though. No les a voice than Julian Cope has some very nice things to say about this music:

“Alice through the Looking Glass is every bit as imaginative, free-flowing, effervescent and absurd as the Carroll work that inspired it. A small-scale forgotten classic that demonstrates the very best qualities of music as an art that is created because you enjoy it, rather that simply for the fact that you’re being paid to do it”

The album has become a significant artefact for those with an interest in such sounds (hence Cope’s review) and a BBC Radio 3 documentary about it was produced in 2017. Amongst collectors these original albums fetch up-to £1000 and are held up as the authentic pastoral psych-folk album, compared with the likes of ‘Piper at the Gates of Dawn’ by Pink Floyd.

Howell Around

Several more projects with Ferdinando were completed and the links with theatre contimued as they worked with the Whizz Theatre Company. That material has not been released yet and is intruiging as Howell says “some of the later stuff also using(sic) early synthesis techniques, which would be of interest to anyone keen on vintage electronics.”

Although he was supposed to be studying law Howell developed a studio at his parents house and at some point it became clear that he wasn’t going to do anything but music. After a stint working at Glyndebourne Opera he took a job as a studio manager at BBC Radio. A move to the Radiophonic Workshop was a natural step from there.

Several more projects with Ferdinando were completed and the links with theatre continued as they worked with the Whizz Theatre Company. That material has not been released yet, but it’s intriguing, as Howell says “some of the later stuff also using early synthesis [sic] techniques, which would be of interest to anyone keen on vintage electronics.”

Although he was supposed to be studying law, Howell developed a studio at his parents’ house and at some point it became clear that he wasn’t going to do anything but music. After a stint working at Glyndebourne Opera he took a job as a studio manager at BBC Radio. A move to the Radiophonic Workshop was a natural step from there.

Howell started at the Workshop in the usual way, creating ditties like ‘Bus Timetable Alteration Ident’ (1974) for BBC Radio Brighton and – one of my all-time favourites – the series ident for BBC Schools’ ‘Merry-Go-Round'(1975) (see ‘BBC Radiophonic Workshop – 21’ REC 354). By his second year he was producing work that would find its way onto ‘Through A Glass Darkly’ with ‘Space For Man’ (1975) and then he started into The Body In Question in 1977, and we’ll back to that later. Meanwhile his way with a tune had not gone unnoticed and at the BBC there were plans afoot to raise his profile.

Producer’s Choices

The Workshop was a marketplace for the composers long before Birtism opened up the closed shop of BBC production. Interviewed for ‘Special Sound’ about the genesis of ‘Through a Glass Darkly’, Howell explained that he felt he was losing out to Paddy Kingsland on commissions. Having arrived some four years after Kingsland, he was evidently seen as a second best option by producers looking for a pop composer. As a fellow guitar player he was also being pigeon-holed as a substitute axe-man, when that kind of music wasn’t much in demand at the Workshop anyway. Now that the synthesizer was pre-eminent he needed to get his chops as a keyboardist better known. During 1978 Howell was in the middle of an epic 14-month project for ‘The Body in Question’ (which we’ll be going back to later) but as a relief from such an all-consuming project he plotted an escape from his colleague’s shadow.

Peter Howell was the first composer to come into the Workshop with published work already out there on vinyl, albeit in a small way. Knowing that Paddy Kingsland’s ‘Fourth Dimension’ album had gone down well with BBC Records, Howell pitched the idea of a concept album. This seemed to press the right buttons at the label because it was “what the big boys were doing”.

Conceptual Start

The definition of a concept album can be stretched to cover range of meanings – and is easily mocked for its pretentions in what is supposedly low-brow popular music – but it’s generally taken to mean that there was an encompassing idea which is carried through all the tracks on the album, instead of some unconnected songs being collated later to form an album. Jean-Michel Jarre had made a splash in 1976 with ‘Oxygene’, an elegant all-electronic, all-instrumental album of gentle melodicism. By 1978 there were a slew of electronic albums being made by long-haired Europeans. As well as Jarre, the likes of Vangelis, Ash-Ra Temple, Tim Blake, Steve Hillage, Rick Wakeman et al were all making serious-ish synth music and selling by the million. Whereas Paddy Kingsland had been dipping a toe into a burgeoning genre, with what was essentially still seen as novelty music in a pop style, Howell was joining the ranks of millionaire hippies with intimidating stacks of expensive keyboards. As the Workshop at least had the expensive synths bit partially covered, here, clearly, was an opportunity.

At one time there was even the idea that Howell would join the ranks of the superstar knob twiddlers. It’s not a ridiculous idea. He wasn’t a bad looking young chap and in hindsight the material was there. But pop music doesn’t work like that and experience with his earlier music projects hopefully kept Howell’s sense of perspective.

Through the darkly side of the moonlighting

Having secured the label’s support, Howell set about making his mark. Working after-hours and grabbing whatever was left lying around and whoever was passing by or in his contacts book to help out, he pieced together the album alongside his day job. Composers at the Workshop never worked regular hours, anyway, and as long as he was getting his other commissions done, the benign dictator Desmond Briscoe was happy to let his staff indulge themselves a little. Especially if BBC Records a keen on the idea and there would be good exposure for the Workshop. There was also the genuine worry about burn-out and, although technically it was more work, this was an outlet.

Howell wasn’t entirely alone in his endeavours either. Here’s a quick run-down of the other musicians credited on the sleeve.

- Terrence Emery – Timpani. Emery was part of the BBC Symphony but he had earlier lent his percussion to The Changes for Paddy Kingsland. This was an example of the convenient location for the Workshop at the home of the BBC’s Orchestra at Maida Vale. As far as I can tell he may only have played on ‘Space for Man’ which was recorded before the album work started,.

- Howard Tibble – Drums. Shakin Steven’s drummer! See also Sing For Joy REC 328. As with Emerey, he may have been only on Space for Man.

- Brian Hussey – Drums. Hussey was a Howell collaborator from his pre-Radiophonic days, who appeared on A Game For All Who Know and Fly Away. I guess it’s his stick work on all the other tracks apart from ‘Space for Man’

- Tony Catchpole – Guitar. Catchpole had served in The Alan Bown Set and The Alan Bown! in the late sixties.

- Des McCamley – Bass Guitar. Other than his producing a few records I could find little else about him.

With one exception, it was an entire album of high quality new material. It almost certainly helped his profile within the BBC, and presumably put to rest any doubts about his abilities. Alongside the success of his music for ‘The Body in Question’ Howell became very well established and went on to tackle the most difficult commission of all at the Workshop. But that’s for next time.

Album Title & Concept

The working title of the album was ‘In the Kingdom of Colours’, which is a pretty good name and captures the eclectic nature of the album. Whatever it’s merit it was dropped in favour of something more, err, theological? It’s interesting to note on Howell’s own website that he lists the album as ‘Through a Glass Darkly (In the Kingdom of Colours)’, suggesting that he was quite happy with the working title and just maybe his first choice was over-ruled by BBC Records. The album was co-produced by BBC Records stalwart Mike Harding. As we’ll see though, there’s more in common between those apparently disparate phrases than, ahem, meets the eye. The first three tracks on side two seem to fall into a loose theme of colours and royalty with ‘Caches of Gold’ and, more obviously, ‘Magenta Court’, followed by ‘Colour Rinse’ – which isn’t royal at all. By, ‘Wind in the Wires’ the theme as been lost. Caches of Gold also prefigures the South American setting of The Case of the Ancient Astronauts. El Dorado and lost gold being another part of the mystery of the ancients.

Let’s Get Biblical

Through a Glass Darkly is a biblical quotation, taken from 1 Corinthians 13:12. The first part of the quote, in verse 13:11 is perhaps more recognisable:

11 When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

12 For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.

The reference to the imperfect glass (or mirror) is a metaphor for how believers can only know god approximately. The phrase was used as a title for several novels in the 50s and 60s but mostly famously for the Oscar winning 1961 Ingmar Bergman film.

Childish Things?

There may be a hint there that Howell’s previous work was now considered by him as ‘childish things’ but that’s probably pushing things too far. There is, though, a fairly clear link back to the ‘Alice through the Looking Glass’ album Howell had made nearly a decade earlier. It’s tempting to conclude that he was playing with the Through the Looking-Glass/Through a Glass Darkly idea. Through A Glass Darkly is a significantly more accomplished work than that older album though, so there may yet be a bit of nod to putting away childish things. Howell was only twenty when the previous album had been produced and he probably felt he’d made significant advances by this point.

The title should perhaps have a question mark at the end of it though. As we look at the sleeve, there are meanings within the title and working title that the imagery throws a lot of light on to.

Sleeve Design

First of all, the typeface is called Baby Teeth and it was used on lots of records, including the French single release of Money by Pink Floyd. The design has its origins in a sign in Mexico and always reminds me of the simple geometry of Aztec designs, which could be a nod to Erich Von Daniken – more on him below.

A view from space of the earth; through an open patio door; and the earth is merely a globe? Unusually there is no design or artwork credited on the sleeve, so we are left to wonder who, as well as why. Perhaps things will become a little clearer if we recall the phrase ‘a window on the world’ – a metaphor often ascribed to television and radio. As Howell was in that business, and the music was supposed to be for such programming, we have a meaning! Furthermore, if the dark glass of the title is the window and we can only see through it imperfectly, then all we can see is a model of the world, and not the real thing. Yes, well, I think there’s a discernible link between the title and the artwork there. The backdrop of space covers the bases for the cosmic album closer, ‘The Astronauts’, and catches the eye of the sci-fi and technology minded consumer. And if I reach just a bit further (stay with me), the patchwork of countries on the globe is in some sense a kingdom (or, are kingdoms, I suppose) of colours. Right?

On the back cover we have a prismatic cube through which we can see space and, oh! hold on. Do I need to explain further, if I say spectroscopy? Okay, for those of a less scientific bent. By means of a prism, Isaac Newton demonstrated that sunlight was actually a combination of the colours of the rainbow. Later, it was explained that everything that emits light, from stars to burning metals, could be identified by means of that light’s spectrum and more crucially the dark bands between them. You can literally see what atoms are emitting the light. That’s how we know what stars are made of. A kingdom of colours through a glass! I should just make a nod here to Pink Floyd’s colossal hit concept LP, ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’. Evidently, using the refracted light through a prism motif would have been too obvious a choice here, but if they hadn’t got there first it would have been an ideal image.

So there’s your concept. You can see the entire universe through a prism. Ancient knowledge suggested we could never know the universe, via God. Or at best, we could only get a darkened impression through imperfect ‘glass’. Once glass was made clearer there was a way to see all the way back to the start of the universe. Through A Glass Darkly? A Kingdom of Colours, more like.

Multi-track Review

Through a Glass Darkly – A Lyrical Adventure

With a flourish of piano we’re off and immediately into a space-y intro, as if to accompany a journey through the cosmos. Then, the piano returns us to earth and for a moment it sounds like someone might start to sing, as a jazzy overture seems to be setting a stage. However, this hands off to more synthesizer atmospherics before being re-joined by more piano, this time with more classical portents. The clear tones of ARP Odyssey synth are in evidence as we move through a variety of moods. At this stage the most obvious influence is the classical reworkings by the late, great Issao Tomita. After five minutes things are abruptly halted and a brass line heralds a new movement with a baroque influence. The piano is back again, as the restless adventure continues with back and forth between the keyboard instruments moving into more romantic territory. After several reworkings of the same figure, the mood changes again and we dissolve back into a cosmic vibe. Discordant tinkling (courtesy of the CS-80’s ring modulator) give way to more thematic and melodramatic piano. Howell is really showing off his piano playing chops here. Once that’s done, things take a darker turn. Deep rumblings from the borrowed timpani are overlaid with some spooky modern piano and a John Carpenter-esque bassline emerges as the drums build into a march. More percussion and flutey parts add a distinctly martial tone. We’re only fourteen minutes in! We’ve taken another turn as piano scales plink menacingly, but then a single sustained synth string line holds as cymbals build a new rhythm. A now familiar synth lead is getting us ready for – wow – latin? Bernstein? piano chords, then synth chords and ascending single note synth bass that lifts the spirits for an air-punching new part that then fades off at 17 minutes. Now we’re hearing previous phrases fading back in. The intro section is back, and other sections, then with a cymbal swell the piano returns for a cantering reprise, whilst various other synth and percussion instruments pick out a single note on the first beat of every second bar until they all fall in for one last resounding note. Recombining the colours of the rainbow to form white light, maybe.

Caches of Gold

The intro to this is quite wonderful. Chimes and a delicate vibrato string synth build a superbly mysterious mood over the first minute and half. You can almost touch the gold! Then, well, the spell is broken somewhat. A drum kit and bass backing underpin a whimsical synth line that then gets rockier and back to whimsical again, and you wonder what happened to the, err, wonder.

Magenta Court

Written for the album, this is on more than nodding terms with Emerson Lake and Palmer’s ‘Fanfare for the Common Man’ (1977). Sky were probably taking notes, right down to the Tristan Fry tom fills. Sky’s ‘Toccata’ charted the year following Through A Glass Darkly but that band of session musos, led by classical guitarist John Williams, were at a bit of an advantage in terms of production and musicianship. Still, BBC Records and Howell himself must have allowed themselves a rueful smile. In many ways The Radiophonic Workshop were running parallel to the library records that Sky members such as Francis Monkman (see ‘Hypercharg’e RESL 95 and ‘The Achievements of Man’ BBC Children’s Themes REH 489) were turning out for Bruton Music et al. What I am saying is that Howell was hitting the absolute sweet spot for progressive rock and synthesizer-embellished thematic music. Sky may also have looked enviously at how Howell was able to get his own album out, and wanted in on that action. A middle section shows off a bit of vocoder oddness that prefigures some of the Doctor Who theme work that was to come. Then Howell’s back to a freezing cold empty stadium in Montreal of the mind*, to see us out.

*Check the Fanfare for the Common Man video, if you wonder what I’m on about.

Colour Rinse

We’re a long way from prog now though. This could be the theme to a sitcom about a hairdresser’s. I mean that as an endorsement, by-the-way. It’s a departure from the rest of the album in mood, but there was a need to show versatility as well as show off, so why not? This track ends the colour theme begun with Caches of Gold. I suppose these three may have been the start of the album and the colours theme was watered down by the other pieces as things progressed.

Wind in the Wires

Of course Howell could not leave guitars off the LP completely. Whilst there was a bit shredding on Magenta Court, this is a return to his folk music roots. And a most tuneful number it is. Layers of Jansch-like acoustic guitars, gentle drumming and softly whistling synths. I can imagine this backing some pages from Ceefax, or in the countdown between schools programmes. And again, I mean that in the best possible way. A quietly charming marvel.

The Astronauts

This track is actually two works segued together. On ‘BBC Space Themes’, released the same year, the full title is given as ‘Space For Man and The Case Of The Ancient Astronauts, The Astronauts’ – except that’s the wrong way around.

The case of the Ancient Astronauts

The first part of this piece was created in 1977 for the BBC Television science strand Horizon. ‘The Case of the Ancient Astronauts’ was a thorough debunking of the claims made by Erich von Daniken that mankind’s progress had somehow been kick-started by alien visitors. Howell’s music plays through the introductory part of the documentary whilst the narrator describes Daniken’s thesis, over a sequence of stock footage clips of space, earth from space, space craft and primitive peoples. It’s got about a dozen sections and works with the pictures as perfectly as you’d expect. It captures the mystery and majesty of the space–aliens-meet-humble-humans idea and you think Erich would have approved of this accompaniment to his narrative. In fact, someone had already done such a job. In 1976 Absolute Elsewhere released an album ‘In Search of Ancient Gods. – An Experience in Sound and Music’ based on the books of Erich von Daniken. You have to wonder if Horizon’s producers hadn’t brandished this at Peter Howell in their first meeting. Or maybe Howell had waved it at BBC Records.

EDIT

Howell spoke briefly about his process for The Astronauts on NTS radio in November 2018 (https://www.nts.live/shows/guests/episodes/radiophonic-workshop-sci-fi-b-sides-special-20th-november-2018). He was asked about the emotional versus the technical process to composing and he explained that he has to work at something until he likes it. In other words, something ‘good enough’ technically is not satisfying to him, and he has to keep going till it is feeling right emotionally. Then he told a story (which, he adds, was probably little known) that he had completed a recording session with live musicans which hadn’t gone well. Whilst walking back to his studio though, he had the idea for what became The Astronauts. He then junked the unsatisfactory recording session he’d presumabley spent all day on, and spent all night creating a new piece in his studio.

Space For Man

The other part of the piece seems to come from another Horizon programme, called ‘Space for Man’ (Workshop tape TRW 8199). I cannot find this programme in the BBC Genome database but it was made around the time of the Apollo/Soyuz links-up in July 1975. Interest in space exploration amongst the general public was rising again, after the collective shrug that led to the end of the Apollo moon missions. This programme looked at what the space race had ever done for us, from satellites to computers. It was then reused in 1976 for an edition of Worldwide, which was a long running series “presenting documentary reports made by television stations worldwide” (TRW8362). I don’t know which edition it was used in. Maybe the one about satellite TV in India. Or the one titled ‘Russia Though the Looking Glass’* which was two hours of Brezhnev-era soviet TV.

*Another link to the album concept there?

Musically this piece starts with a sequenced bassline that is pure Tangerine Dream. Technically speaking, the Workshop were able to surpass the Germans by dint of the EMS Synthi 100’s superior digital sequencer. The Tangs were known for their signature use of the Moog 16-step sequencers to lay down the basis for 20-minute dreamy moodscapes. You won’t hear a more sophisticated run of notes from them as you do on ‘Space for Man’ though! Except, the Delaware was never used. It had three-channels of 256 steps to play with but Howell shunned it and did everything on the ARP Odessey “multitracked to kingdom come”, Howell explained to Neibur in Special Sound.

Edit. I had originally been keen to wave the flag for the advanced sequencer on the Synth 100 and, as I go on to say below, point out how Howell had stolen a march on Tangerine Dream. Unfortunately, I could only find evidence that he hadn’t used the Synthi. Now, I’m very pleased to be able to come back with a Peter Howell quote that restores my original point. Talking to Tony Hadoke on his Who’s Round interview series for Big Finish Audio he talked about the use of the Delaware for the failed Doctor Who theme version:

The Delaware – big Synth hundred – was really their pride and joy and indeed I used it on several occasions; the front of my Astronauts track; the sequenced front on that, that’s Synthi hundred.

So, there you are. and now back to my original point.

It’s been noted that Paddy Kingsland largely shunned the sequencer when he was working on the tracks for ‘Fourth Dimension’ because it was too limited for his style! Here Howell takes the basis of much of the mid-to-late 70s Tangerine Dream heyday and does tricks in 1975 that they weren’t doing till years later. It’s just a shame that this track wasn’t released until 1978! The lead part is a soaring brass fanfare with liberal phasing effect on the harmonies. Sprinklings of trilling alternate with the lead, whilst snare and timpani rolls add to the drama.

Lingual Music

According to Tim Worthington, ‘Space for Man’ was also used for a Radio 3 programme produced by Desmond Briscoe and called simply Workshop. The timeline for this is unclear and I can’t find any other source for this, but Tim has had access to archive information from the Workshop. Now excuse the digression here, but the main credit for ‘Workshop’ goes to a piece by sound poet and ‘lingual music’ artist Lily Greenham. Her piece ‘Relativity’ is composed entirely from the spoken word and includes the voices of Richard Baker (brother of John) and Baron Silas Greenback himself Edward Kelsey, among others.

“An exploration in stereo, where the basic elements are spoken words and parts of words: no other sound is used. From a starting point of the human voice, three-dimensional drawings and visual lettering patterns, the electronic realisation has produced a form to be listened to rather as music than a poetic work.”Radio Times, Issue 2683, 1

The Astronauts b/w Magenta Court

As an extra boost to the album’s prospects, a single was released in March of 1978 – RESL53. It features the same versions of The Astronauts and Magenta Court as the album and there’s not much else to say, other than it didn’t chart. No shame in that though. The album didn’t chart either and this single was toughing it out against disco and punk in their pomp, as well as the all the rest, creating fierce competition. Not that BBC Records would have been too upset either, as they scored a minor hit with another single in the same month. The Theme to Hong Kong Beat by Richard Denton and Martin Cook manged a respectable 25 placing and an appearance of a promotional video on Top of The Pops. Let’s pause here and imagine what a live appearance by Peter Howell might have been like if he’d had similar success…

‘The Astronauts’ had its shot at the big time and missed, but it was to get another outing on 7″ single, abeit in a supporting role. That’s a story for another time though.

The case of the ancient The Astronauts tapes

The full origin of The Astronauts is a bit confusing, so here’s a bit of sleuthing around the available Workshop tape archive.

TRW 7973 – Lingual Music – 01/05/74 – Broadcast April 1975

TRW 8199 – Space for Man – 01/06/75 – Not clear on the broadcast date but the Soyuz/Apollo link-up was in July 1975. Could this have been added to the finished Lingual Music programme ahead of broadcast too?

TRW8362 – Worldwide (copy of Space for Man) – 01/03/76 – Unclear which edition this is from.

TRW 8607 – Space Music Copies – entry date 01/05/77 – probably copies of Space for Man and The Astronauts for ‘BBC Space themes’. This seems to be when the two were first combined

TRW 8646 – The Case of the Ancient Astronauts for Horizon – 01/08/77 – Horizon broadcast November 1977.

TRW 8653 – Through a Glass Darkly (In the Kingdom of Colours) – 01/08/77

The Astronauts (RESL 53) – March 1978

REC 304 – Through A Glass Darkly – 1978

REH 324 – BBC Space Themes – 1978 (but probably at the end of ’78 or early the following year, as it was being promoted in the Radio Times from 6th January 1979).

TRW 9389 Doctor Who theme (RESL 80) – 01/06/80 – The Astronauts taken from the TAGD tape TRW 8653.

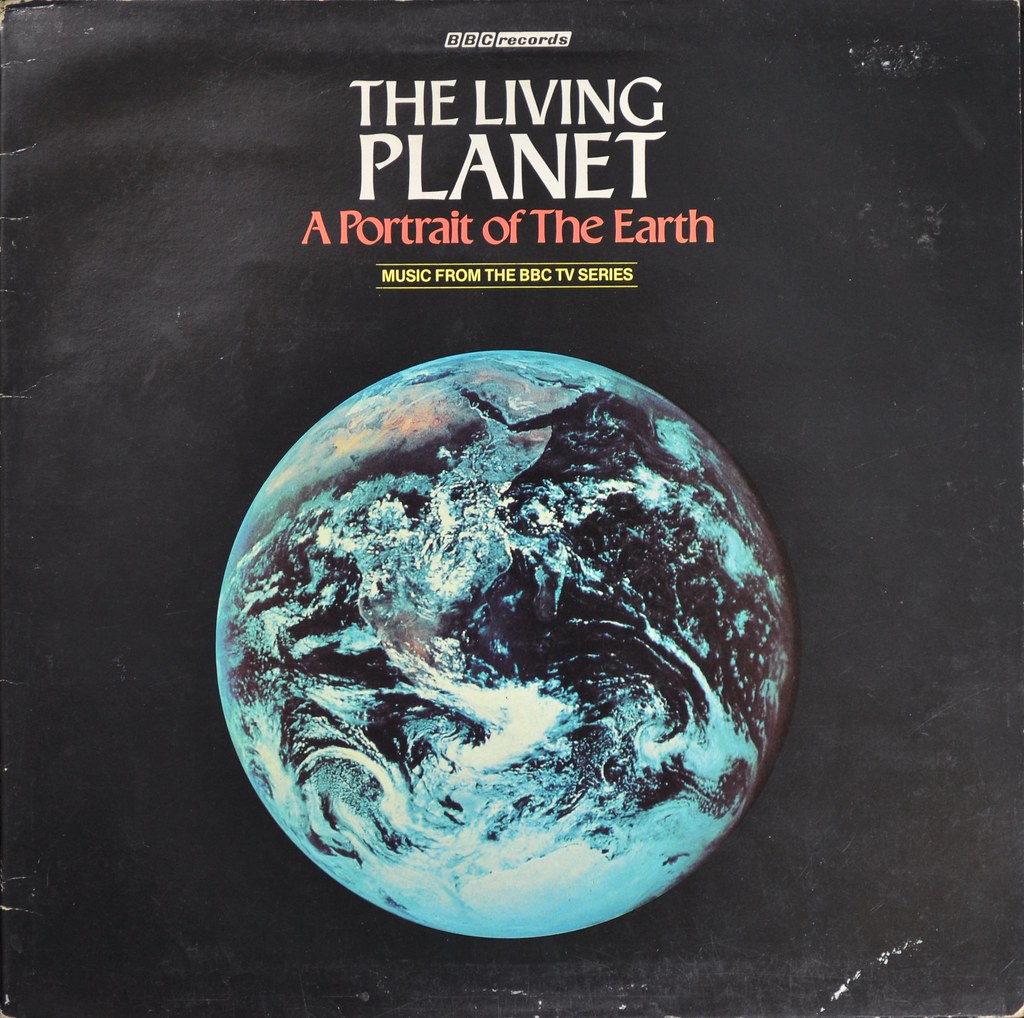

The Living Planet – A Portrait of The Earth

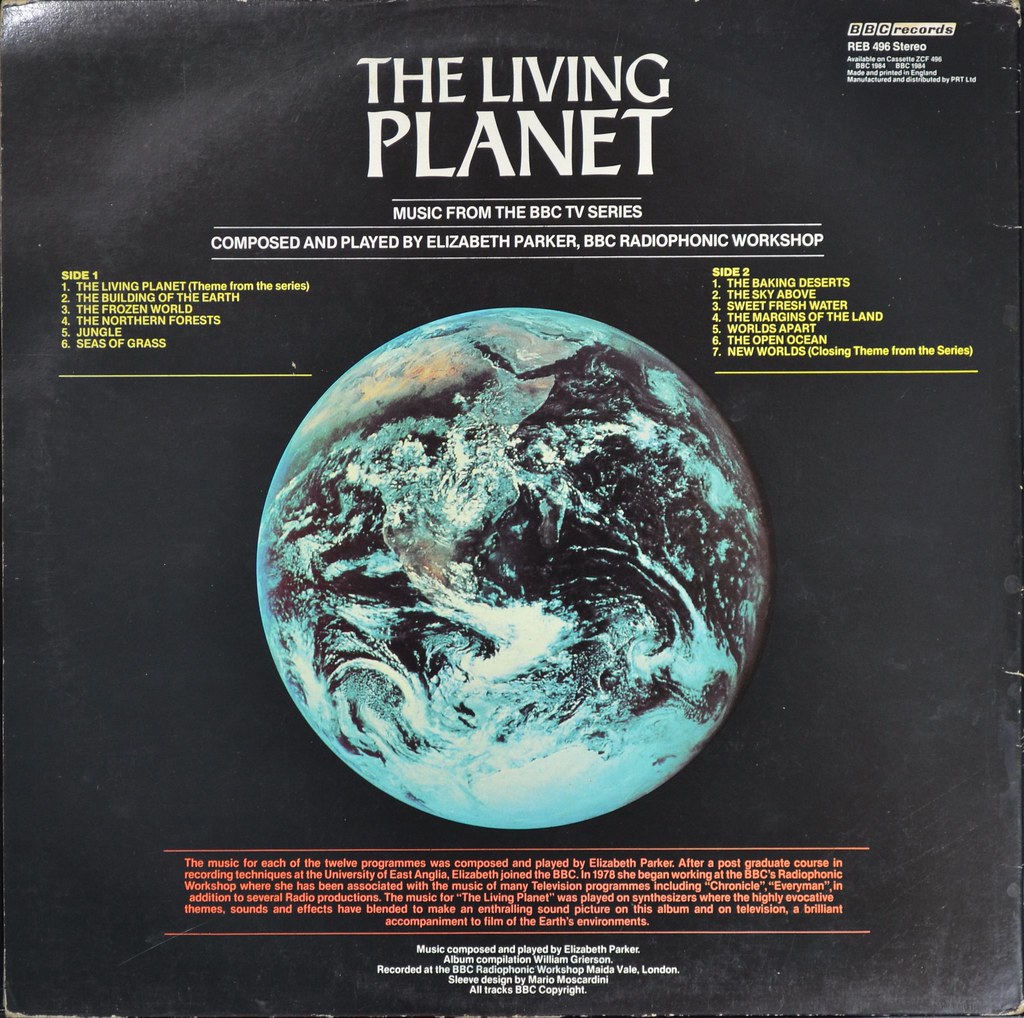

Elizabeth Parker

“I always had this idea that I could make electronic music sound more musical” Sound on Sound interview

Elizabeth Parker joined the Workshop in 1978 and stayed till the bitter end, in 1996. She represents the fourth generation of composers at the Workshop. The first generation were the original BBC producers and engineers, like Desmond Briscoe, Daphne Oram and Dick Mills; the second were the likes of Delia Derbyshire and John Baker, who took music concrete to the next level. The third generation were musicians first, and in the vanguard of synthesizers, multitrack tape machines and scoring full programmes – Peter Howell, Paddy Kingsland and Roger Limb. Then, the first generation started influencing development of the next generation.

And now, from Norwich, It’s the Trygg of the bleep!

Parker got her break into electronic music whilst at the University of East Anglia, where they were starting one of the first courses in ‘electro-acoustic’ music. This was in 1973, and she was invited to take part in post-graduate studies. The course was set-up by Trygg Tryggvason, who was teaching recording to musicians, and Tristram Carey, who was introducing them to electronic music. Parker admits to being bemused by his formal approach and as the quote above states, she was interested in where it was going rather than what the fundamentals of subtractive synthesis were. Still, at least she was introduced to the EMS Synthi 100 there, and this set her off on the path which led to the Radiophonic Workshop. Incidentally the Synthi 100 at the university eventually ended up with Daniel Miller, the founder of synth-pop label Mute records. It is one of only a few in a working state still in existence. But I digress…

“I’d first heard of the Workshop while I was at University and I thought they sounded absolutely fantastic.” Scorpio Attack interview

Masters and then Servalan

After completing her Master’s in electronic music, she got a job at the BBC as a studio manager and in the time-honoured way ended up at the Radiophonic Workshop. No doubt her Master’s and her association with Carey did her prospects no harm. She joined at the start of 1978 and fortunately this was a time at the Workshop when more ‘musical’ electronic music was coming into its own. But first she would have to serve her apprenticeship.

Avon Calling

Almost immediately she was given the job of providing special sound for sci-fi series Blake’s 7. Richard Yeoman-Clark had decided to leave half-way through season 2 and, after a stint filling in for Dick Mills on Dr Who, Parker put herself forward. That ‘can do’ attitude led to many other commissions (some of which we’ll come back to later) and by the time the prestigious ‘Living Planet’ project came up in 1981, she was given this rather “plum job”, as Desmond Briscoe described it. No doubt this was helped by Paddy Kingsland’s leaving, but it was not like any other commission either.

12 hours of nature, 19 Hours a day

The BBC’s nature documentaries are renowned the world over and this reputation was established by Life on Earth in 1979. That production had a largely orchestral score by Edward Williams, but he added subtle electronic treatments with his EMS VCS3 and although its theme was fairly Hollywood (it was a co-production with Warner Brothers, after all) the incidental music is as sumptuous and varied as the programme itself. Watched by an estimated half a billion people (!) the next series had some serious (ahem) living up to do.

The Living Planet: A Portrait of the Earth was the ambitious follow-up. Each of the 12 parts examined a different part of the earth, from the way it was formed, to the frozen extremes to the oceans, forests, deserts, jungles and so on. The final part looked at man’s place on earth and role in its future. The series premiered on BBC1 in January 1984 and won an Emmy for ‘Outstanding Informational Series’.

Brian Hodgson was asked about providing music from the Workshop. By this time they were churning out scores for Dr Who, so the days of signature tunes and special sound only were gone. Gigantic, flagship nature documentaries were also in their reach. He recommended Parker, who was then asked to submit a 15-minute demonstration reel, complete with a theme. This was done in May of 1981, so fully two and half years before broadcast. With the support of David Attenborough, this demo got the commission and it was probably at this point that she was able to get the pricey sampler she needed for this major undertaking. Interviewed for the ‘First 25 Years’ book Parker said in relation to this project that “1983 is obviously going to be a very busy year…and I might be working nineteen hours a day”. She goes on to say how lucky she is and it’s what she always wanted to do.

Parker started proper, sometime in 1982, after planning out what she wanted to do whilst at home, pregnant with her second child. On her return, she worked alone at Maida Vale in her studio with the occasional visit from the producers, including Attenborough himself. Then she would travel to the BBC’s Natural History unit in Bristol and work with the foley artists and sound mixers there. Her two and half years matching sound effects with music and action on Blake’s 7 stood her in good stead.

The programmes and the score were lauded so BBC Records must have been very pleased to release an LP of excerpts.

The Making Of…

In the sleeve notes to the 2016 reissue, Parker states that her dream was to for the music to become “part of the natural environment, rather than an obvious add-on”. As we’ll see below, she utilised the relatively new technology of sampling to achieve this.

Satisfyingly, we can actually look at exactly how the music for the series and this album was made. Being such a prestigious production meant that a documentary exploring the making of The Living Planet was produced and (yes!) an interview with Liz was included. This appears on the DVD, but thanks to YouTube we can all watch it and get a guided tour from Parker on exactly what she used to create the score.

After the obligatory establishing shots of the exterior of Maida Vale Studios on Delaware Road and a stroll down the famous corridor, Parker talks through with the presenter Miles Kington (of Instant Sunshine fame) the technology and techniques she employed. She explains how she samples sounds and uses effects to alter and reframe the familiar – bottles and other junk – to make up the audio palette for the score.

The first piece to be finished was the title music and this came before the sampler was available. Instead, Parker used the Yamaha SY-2 monophonic synthesizer. This was a kind of baby nephew of the CS-80, which Peter Howell made great use of on various projects. The theme’s motif makes a return on The Baking Deserts, Margins of the Land etc. and there is consistent use of the SY-2 or similar tones and phrases throughout. Parker was unhappy with the result though, and it appears it was produced for the original demo in ’81 and never intended to be the one used in the end. She explains in the reissue sleeve notes that it was created prior to the arrival of the PPG Wave System, which would become her main instrument for the series. You can see why it was frustrating that there was no time left to redo it. Digital synthesis and sampling were hitting the mainstream by the start of 1984 and the parps of a charming little old analogue keyboard made of wood was not really what was called for. More importantly for Parker, her whole thesis of using natural sounds and utilising electronic music in a more experimental setting was undermined. It’s still an effective and evocative piece, though.

Analogue to Digital Conversion

As we saw with The Soundhouse LP, technology had moved on since the analogue heyday of the 70s. Whilst still in use a lot up to 1984, analogue’s days were numbered and digital was in the ascendant. The PPG Wave System was a German product and another example of the computer-with-a-keyboard attached apparatus, like the Fairlight. These early samplers provided for the first time a way to record sounds into the memory of the computer and play around with them musically. The concept of natural sounds as the basis for music scoring the natural world was not new (see Delia Derbyshire’s ‘Great Zoos of the World’), but it was now possible to score 12 hours of TV in – well, it was still many months of work. But, it would have been unthinkable with tape machines and razor blades.

On the track ‘Jungle’, you can clearly hear the sound of blowing across the top of a bottle, which was still a pretty neat trick for a synth in 1983 but quickly became a standard. The Wave System was actually a precursor to the mighty wavetable synths of the late eighties from Korg and Roland, as well as the cheaper samplers which followed. The Wave 2.2 was a synth that happened to use samples for its waveforms, instead of simple oscillators with limited shapes. The wave-shaping usually came from the filters removing harmonics, but with wavetables stored digitally you already had the interesting tones built in, and the filter became an additional feature. Although wavetables were extremely useful for keyboard instruments, the synthesis element was reduced and eventually this led to a rather stale scene for synthesizers as the cheaper computerised machines took over and became sample playback machines. In turn that led to the veneration of the older machines and eventually, when the economics became viable, a complete revival that is now in full swing. At this point the waves were all brand new ear candy, but – as electronic music pioneer Milton Babbit noted back in the 60s – ‘nothing gets old faster than a new sound’.

Fortunately, The Living Planet is a more subtle and considered suite of music than the average pop sounds which are forever locked to their particular era. Although there are a few glaringly mid-80s moments from the Wave, the work generally manages to transcend the tools and create atmospheres which are as unfamiliar and uncanny as the pictures.

Crashing Wave

However, the Wave System was still technology, as defined as ‘stuff that doesn’t work yet’.

“….its inner workings were a mystery to everyone, including PPG. One of their engineers moved his fingers over the circuit board until a fault stopped and then soldered a capacitor where his fingers had been!”. Ray White http://whitefiles.org/rws/r05.htm

When I was lucky enough to speak to Brian Hodgson, about this in 2017, he confirmed how awful it was. He pointed out that although it promised much, Parker had to stick to the few functions she needed and leave the rest alone. It didn’t live up to all the hopes they’d had for it.

“It had the endearing habit of crashing at the most inopportune times, driving me crazy, but the potential it offered with its Wave Term sampling was so brilliant that I learnt to live with its bothersome quirks, of which there were quite a few.” Elizabeth Parker 2017

There was a sense in which the Workshop was trialling new technology and experimenting with it for the good of the wider music technology community here. Prominent artists were granted visits to the Workshop and The Pet Shops Boys came round to take a look at the PPG.

The Wave wasn’t the only toy at her disposal though. Vocoders had moved on from the unwieldy EMS device and, instead, the rack-mounted Roland SVC-350 was used to add more expression. Also of note is the Eventide Harmonizer (“sometimes called the fairy dust machine”). This was common in professional studios of the time and was the first digital effects unit. Synth-spotters also get to see a Roland System 100M modular and the more obscure Godwin String Concert by Italian company Sisme, in the ‘making of’ video.

The Living End

As well as providing the contemporary sounds and textures suitable for a cutting edge nature documentary there was still a lot of support needed for the stories unfolding onscreen. The genius of Attenborough is to recognize that there is only so far the facts can take you and the viewer needs to feel invested in the life of the wild creatures. Part of this comes from the music which functions identically to that in drama. Hence we have pieces in the score that follow the actions and ‘characters’, and more lyrical elements are used to carry the sentiments through. Elizabeth Parker’s contribution was to be able to bridge between the formal and abstract electronic music of her predecessors and the more conservative demands of a mainstream nature documentary. Along the way, she realised her dream of making accessible music using electronics in innovative ways. She went on to score many more nature series and a long and successful career in music for TV and radio.

Sources

- https://www.headheritage.co.uk/unsung/review/1747/

- https://whitefiles.org/rwz/zhw/2013_peter_howell_and_john_ferdinando.pdf

- http://thestrangebrew.co.uk/articles/peter-howell-and-john-ferdinando/

- White Rabbits In Sussex

- Worldwide on Genome

- Workshop – Radio 3 – 1975

- Sound 11 – Radio 3 – 1973

- https://www.forcedexposure.com/Artists/GREENHAM.LILY.html

- http://www.muzines.co.uk/articles/the-sound-house/3292

- http://www.elizabeth-parker.co.uk/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Living_Planet

- https://web.archive.org/web/20060813111842/http://www.soundonsound.com/sos/feb01/articles/elizabeth.asp

- http://myblogitsfullofstars.blogspot.co.uk/2013/10/university-challenge.html

- https://www.scribd.com/document/179312220/Nicola-Candlish-PhD-2012-pdf

- http://www.warpedfactor.com/2015/06/the-composers-of-doctor-who-elizabeth.html

- https://www.scorpioattack.com/composer-elisabeth-parker